World Social Protection Report 2024–2026

Universal social protection for climate action and a just transition

Chapter 4. Strengthening social protection for all throughout the life course

For social protection systems to play their key role for climate action and a just transition, they need to provide adequate protection for everyone throughout their lives. Structured along the four social protection guarantees provided in Recommendation No. 202, this Chapter delves into income security for children and families (section 4.1), people of working age (section 4.2) and older people (section 4.3), while section 4.4 focuses on social health protection.

.4.1 Social protection for children and families

Key messages

-

It is time to up the ante. Progress in the extension of social protection has occurred, but access to inclusive and integrated social protection remains elusive for the vast majority of children – only 23.9 per cent of children aged 0 to 18 globally are covered by child cash benefits. This equates to 1.8 billion children of this age range missing out.

-

Given the well-recognized poverty reduction properties of social protection (on both monetary and multidimensional child poverty), this protection gap prompts deep concern considering that children make up more than half of the world’s extreme poor. Today, 333 million children are still living below the extreme poverty line, 1.4 billion children are living below the higher international poverty line and almost 1 billion children live in multidimensional poverty. Some 1.9 billion children – 80 per cent – are at high climate risk.

-

The positive impacts of social protection for children are beyond question. Extensive evidence shows that child-sensitive social protection reduces poverty while also contributing to income security in households, protects against child labour and has broader significance for child health, early childhood development, education and food security. However, in the absence of social protection, these basic conditions for well-being are less likely to be met during childhood, creating lasting conditions that are difficult to rectify in later life.

-

Children, especially those in poverty, are bearing the brunt of the climate crisis. This unfolding crisis is tantamount to “structural violence against children” and compromises their well-being and prospects. It also underscores the importance of making social protection systems more inclusive and resilient so that they continue to achieve their core objectives and support the additional needs that climate change is creating. Investment in social protection for all children is crucial for intergenerational solidarity and equity, and an essential investment to uphold the rights of future generations. It will also support the capability formation and requisite skills development of children that a green transition will demand.

-

To close protection gaps and achieve positive impacts for all children, expenditure needs to increase, especially in the early years. Analysis of age-related spending shows that all children – and the families in which they live – are underserved in terms of social protection, particularly in early childhood. On average, 0.7 per cent of GDP is spent on child benefits globally. Again, large regional disparities exist: the proportion ranging from 0.2 per cent in low-income countries to 1.0 per cent in high-income countries.

4.1.1 The role of social protection in addressing persistent poverty and socio-economic vulnerabilities for children, exacerbated by compounding crises, including climate

Social protection is an investment that contributes to children enjoying their rights and accessing the support they need. When social protection is absent, children are at a higher risk of multiple child rights violations and are exposed to the long-lasting impacts of child labour, disease, missed education, poor nutrition and poverty.

The unfolding climate crisis carries an extremely high poverty risk for children and has been deemed “a form of structural violence against children” (UN 2023e). One in four deaths among children under 5 years old worldwide is the result of avoidable environmental damage and the climate emergency (UNICEF Innocenti 2022). Children are especially vulnerable, owing to the spread of more deadly diseases, lower ability to regulate body temperatures in heatwaves, and malnutrition from greater food insecurity (UNICEF 2023b).

From an intergenerational equity and social justice perspective, readying children for even 1.5°C of warming alone should be sufficient motivation for policymakers to build social protection systems and other key services for all children. Evidence from global research conducted by UNICEF demonstrates that, globally, only 46 parties have included child-sensitive social protection commitments in their key climate policy documents (UNICEF, forthcoming). Ultimately, governments must escalate their SDG commitments to end extreme child poverty and increase social protection coverage of children.

Impact of COVID-19 on child poverty

In the last decade, there has been a large reduction in the absolute number of children living in extreme child poverty. However, during the period 2019–22, estimates suggest that poverty reduction has stalled, and that three years of progress have been lost, mainly because of COVID-19. Poverty would have increased even further without the central role of social protection in containing its impoverishing effects (ILO and UNICEF 2023).

COVID-19 is just one of the compounding crises experienced by children and their families in recent years, suggesting that other global concerns, such as the climate crisis, are likely to act as a drag on the progress needed for children.

Between 2013 and 2022, extreme child poverty rates fell from 20.7 to 15.9 per cent. In real terms, this meant that the number of children living in extreme poverty fell by 49.2 million. Notably however, rates were already at 15.9 per cent in the year before the COVID-19 pandemic. This points to “three years of lost progress” for children living in extreme poor conditions. Estimates suggest that, without this lost time, another 30 million children would have escaped extreme child poverty worldwide (Salmeron-Gomez et al. 2023).

The most recent figures from the World Bank and UNICEF show that 333 million children are still living in households with an income lower than US$2.15 per person (extreme poverty line). At the higher international poverty lines, a staggering 820 million children live on less than US$3.65 a day (lower-middle-income poverty line), and 1.4 billion children are living on less than US$6.85 a day (upper-middle-income poverty line) – or 3 in 5 children worldwide (Salmeron-Gomez et al. 2023). In addition, approximately 1 billion children experience multidimensional poverty, deprived of their basic rights to health, nutrition, water, sanitation, education and shelter (UNICEF 2021a).

Global figures hide the increased risk that many children experience when it comes to extreme child poverty. Not only are there large differences by regions of the world, national income levels and experiences of conflict and fragility, but personal and family attributes also play a role – for instance, children who experience disabilities or have family members with disabilities, or girls and women when compared to boys and men. Families who care for a person with a disability experience both a loss in earned income (lost earnings potential as care time increases) as well as higher living costs due to additional expenditures related to that care. Women and girls are over-represented globally among the poorest and are disproportionately impacted by multiple intersecting deprivations due to social and economic exclusion and restrictive gender norms and expectations. Yet, social protection often fails to incorporate and address gendered risks, needs and opportunities. Many other categories of children are at a higher risk of poverty – such as migrant or forcibly displaced children, indigenous children and children living in remote settings – and this must inform the design of social protection policies for children.

Child poverty risks and the climate emergency

The climate emergency represents a major threat to progress in reducing child poverty risks worldwide. The direct and indirect child poverty risks take different forms from sudden-onset events (for example, flash floods), slower-onset changes (for example, desertification) and environmental degradation (UNICEF 2021b).

Child poverty is both a driver of vulnerability and a result of overall climate risk. Firstly, children in poverty are more exposed to climate risks. Six out of ten children already living in multidimensional poverty are expected to experience at least one climate risk a year, and three out of ten children live in provinces with very high climate risks and a high concentration of multidimensionally poor children (Global Coalition to End Child Poverty 2023).

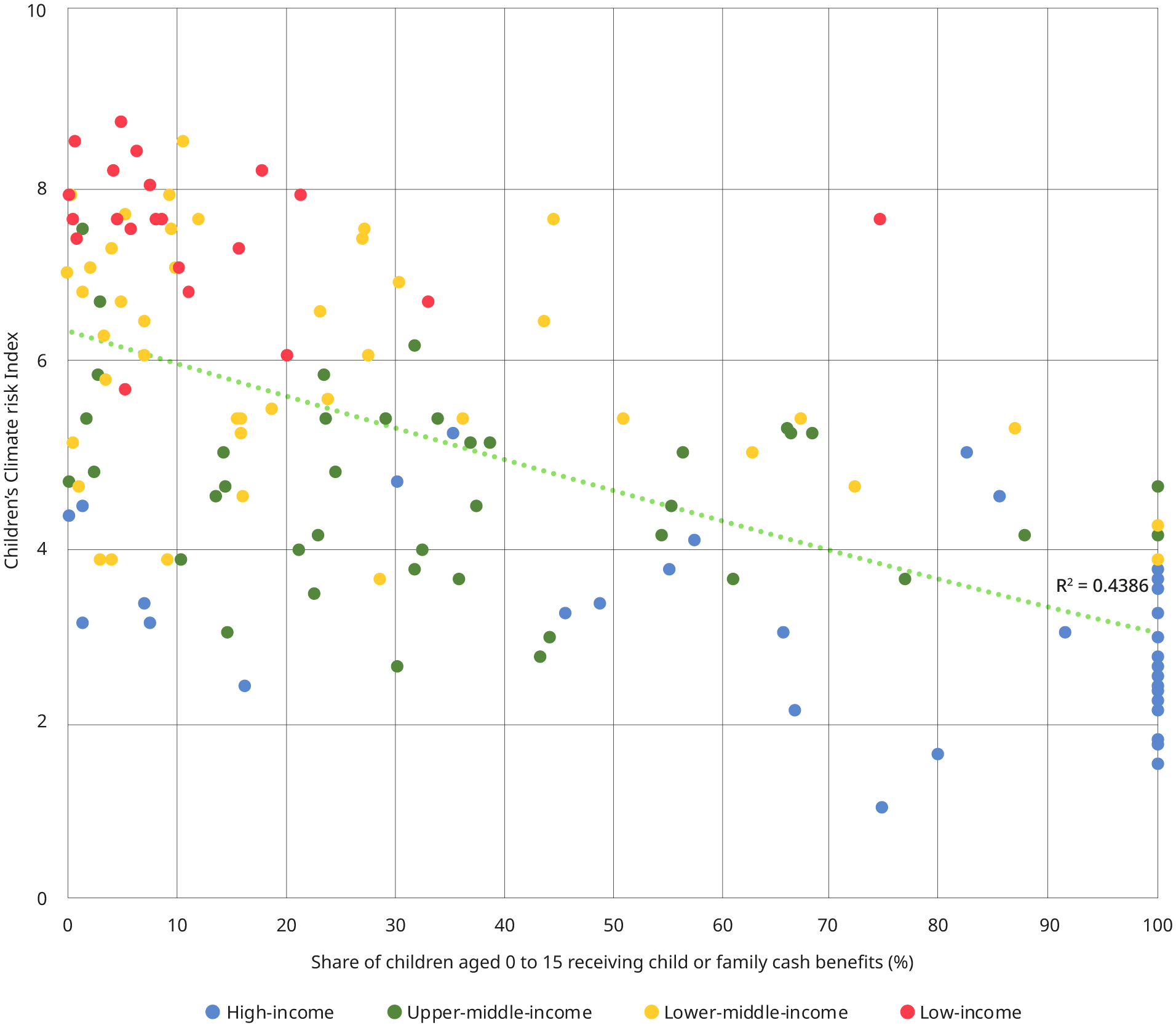

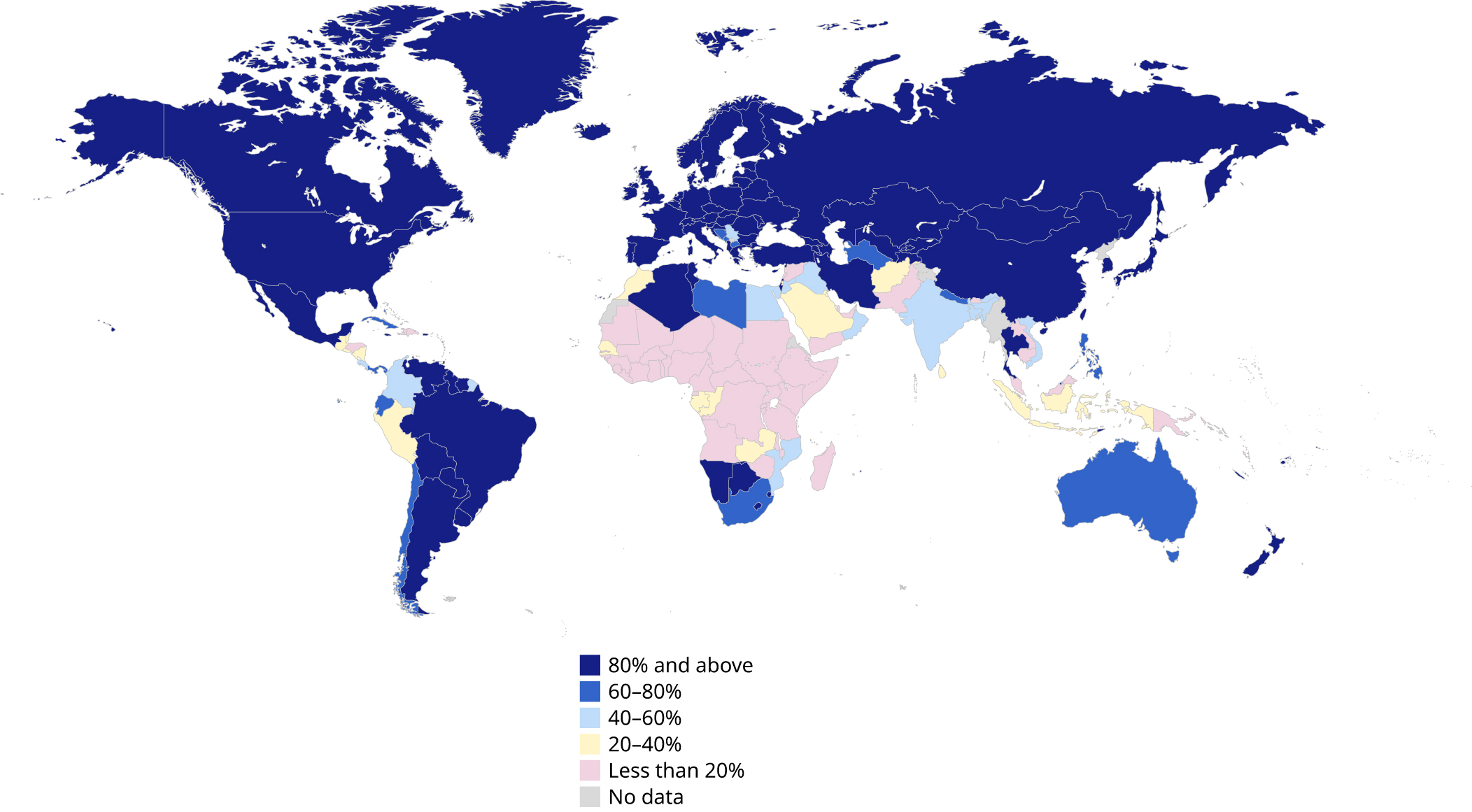

Secondly, lower-quality housing, poor water and sanitation facilities, existing food insecurity, health issues and inadequate access to information, mean that children in poverty are more likely to suffer harm once a climate shock hits. Poor families with children also have fewer coping capacities to respond to negative effects or adapt to a changing climate due to fewer financial resources. They also have limited social protection; children living in higher-risk environments have less access to social protection (see figure 4.5). In high-income settings, children in poorer households and other disadvantaged subgroups also experience the greatest environmental risk and harm (UNICEF Innocenti 2022).

Climate risks are disproportionally exacerbated for those vulnerable to intersectional inequalities relating to race, gender, caste, class and gender (Lankes, Soubeyran, and Stern 2022). These intersectional inequalities impact exposure to climate-related shocks and influence the strategies used to cope with the impact.

Finally, extreme weather events, slow-onset impacts and other climate-related shocks can exacerbate child poverty. They can directly impact families, children’s living standards and poverty risks, by destroying homes, farms and communities. This, in turn, affects productivity and increases the risk of illnesses, including poorer mental health. Indirectly, the disruption of public service provision, like health, nutrition, drinking water, sanitation and hygiene and education – all of which significantly impact children’s access to care, and the destruction of natural resources – have a knock-on effect on child poverty and development (Diwakar et al. 2019; Lankes, Soubeyran, and Stern 2022).

Since poorer people have higher exposure to natural hazards related to climate shocks, and fewer resources to respond effectively, the risks associated with climate-related shocks and stressors need to be addressed. This means protecting consumption, promoting asset building and productivity, and creating opportunities for families to diversify from activities they used to rely on for their livelihoods (Hallegatte et al. 2014) through short-run, rapid, inclusive, climate-smart and targeted adaptation interventions (Hallegatte et al. 2016).

Based on the aforementioned evidence and coverage concerns, social protection and essential services to support children exposed to climate-related risks and families living with climate emergencies are critically needed. Strengthening households’ resilience and coping strategies in response to climate shocks requires investing in robust social protection systems, and enhancing their shock responsiveness. Such systems can be scaled up in advance or in the aftermath of a (climate) shock (Global Coalition to End Child Poverty 2023).

Realizing the right of children to social protection is indispensable for combating child poverty and promoting children’s well-being

Social protection policies are powerful tools in alleviating poverty for children and their families. They protect families at risk of falling into poverty; they help all children connect to key services, such as health and education; and they protect children from other major risks, such as child labour (box 4.1). Overcoming these challenges is essential for realizing the rights and full potential of all children (box 4.2). Ensuring children’s rights to social protection and to an adequate standard of living, health, education and care, and achieving the 2030 Agenda, requires a conducive policy framework that prioritizes the needs and requirements of children and their participation in the process.

Box 4.1 Social protection, child labour and the climate crisis

|

Recent evidence compiled by the ILO and UNICEF (2022) shows that integrated social protection systems are powerful instruments to combat child labour (ILO 2013c). The climate crisis further emphasizes that strengthening social protection is a prerequisite for ending the scourge of child labour. Today, 160 million children are engaged in child labour. That is almost one in ten children worldwide (ILO and UNICEF 2021). The climate crisis will be an additional threat multiplier for child labour (ILO 2023m), primarily through increased poverty, but other channels will also heighten child labour risks. These channels include: changes to agricultural productivity; climate-related extreme weather shocks; climate-driven migration and conflict; health issues; and destruction or degradation of basic services infrastructure (ILO 2023m). The probability of increased child labour makes social protection all the more indispensable as a means to contain this risk. However, most children engaged in child labour lack social protection (ILO and UNICEF 2022). |

Box 4.2 The right of children to social protection

|

The right of children to social protection is underlined in Articles 26 and 27 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which stipulates that “States Parties shall recognize for every child the right to benefit from social security, including social insurance, and shall take the necessary measures to achieve the full realization of this right in accordance with their national law” (Article 26). The United Nations legal framework contains several provisions spelling out the various rights of children that form part of their right to social protection. These include: the human right to social security, taking into consideration the resources and circumstances of the child and people having responsibility for the child’s maintenance;1 the right to a standard of living adequate for the child’s health and well-being; and the right to special care and assistance.2 The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights further requires States to give the widest possible protection and assistance to the family, particularly with respect to the care and education of dependent children (Art. 10(1)). Complementing human rights instruments, international social security standards are also part of the United Nations normative framework, with specific guidance on coverage, adequacy and key policy principles at the heart of a rights-based approach. The comprehensive ILO Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102), sets minimum standards for the provision of family (or child) benefits in the form of a periodic cash benefit, benefits in kind (including food, clothing or housing) or a combination of both (Part VII). The ILO Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202), emphasizes the universality of protection. It sets out that all children should have access to at least a basic level of social security – including access to healthcare and income security – allowing for access to nutrition, education, care and any other necessary goods and services to live in dignity. The basic social security guarantees of the nationally defined social protection floor should apply, at a minimum, to all residents and children, as defined in national laws and regulations and subject to existing international obligations (Para. 6), including under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and other relevant instruments. Representing a rights-based approach strongly focused on outcomes, Recommendation No. 202 allows for a broad range of policy instruments to achieve income security for children, including child and family benefits (the focus of this report), as part of a broader portfolio of interventions. Moreover, this framework provides valuable insight for implementing a life-cycle approach to social protection that is suitably holistic, comprehensive and adequate to address all child rights. 1 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, Art. 22; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966, Art. 9; United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989, Art. 26. 2 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Arts 25(1) and (2). |

4.1.2 The importance of ensuring child-sensitive social protection systems

Entitlement to child and family cash benefit schemes

Child and family cash benefit schemes constitute an important element of child-sensitive1national social protection systems and play an essential role in ensuring income security for families. The proceeding section provides an overview of the legal coverage of such schemes worldwide.

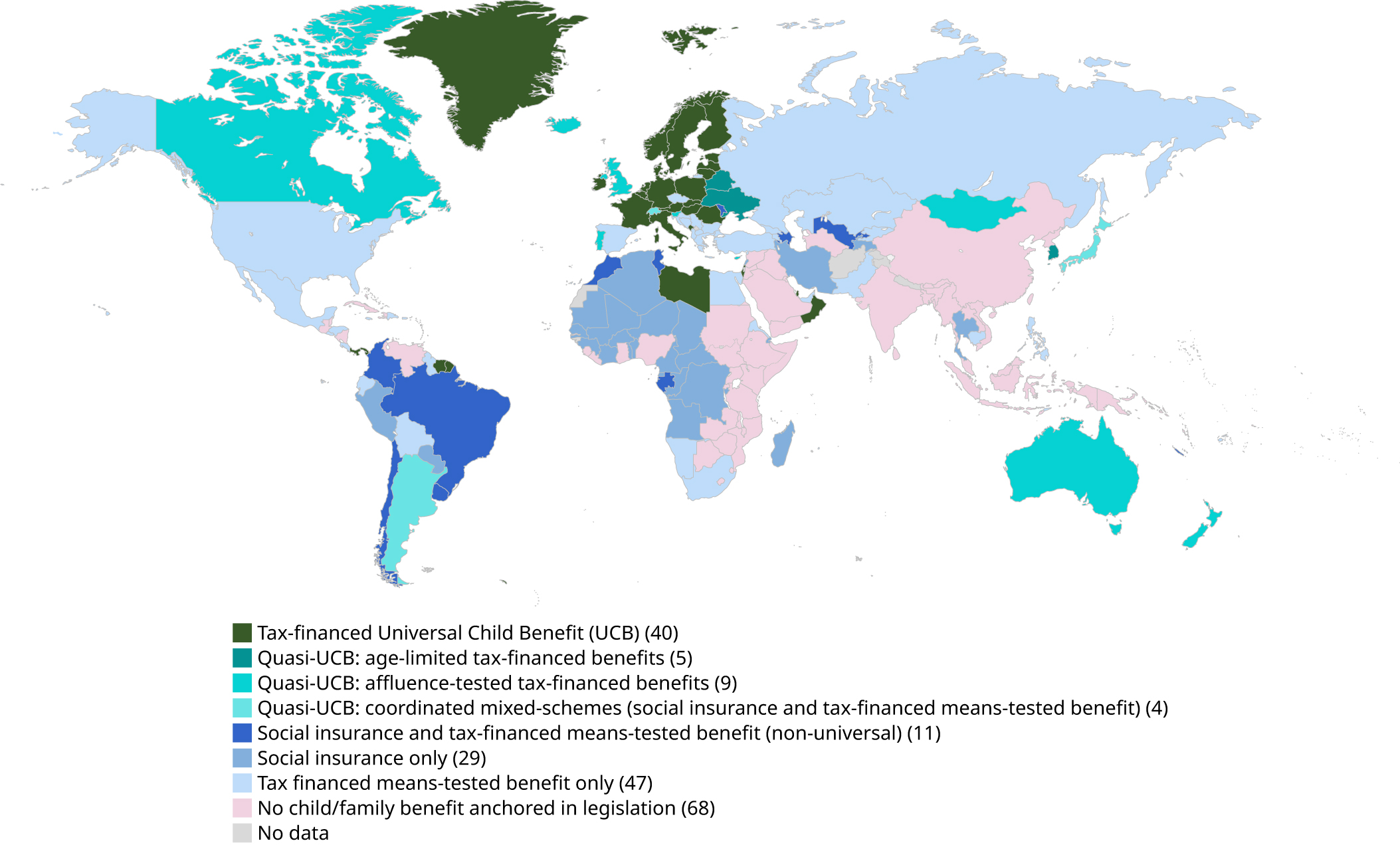

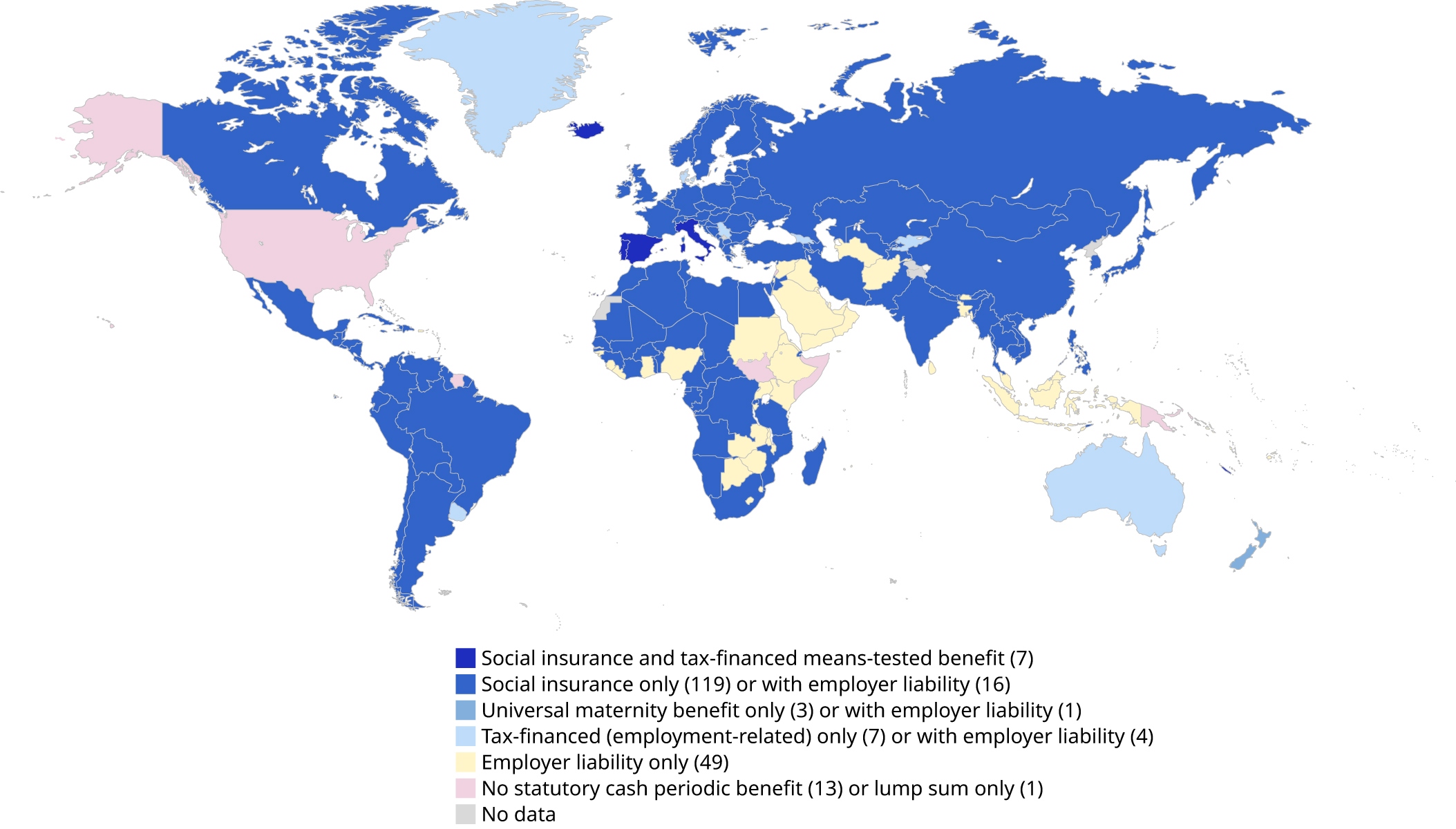

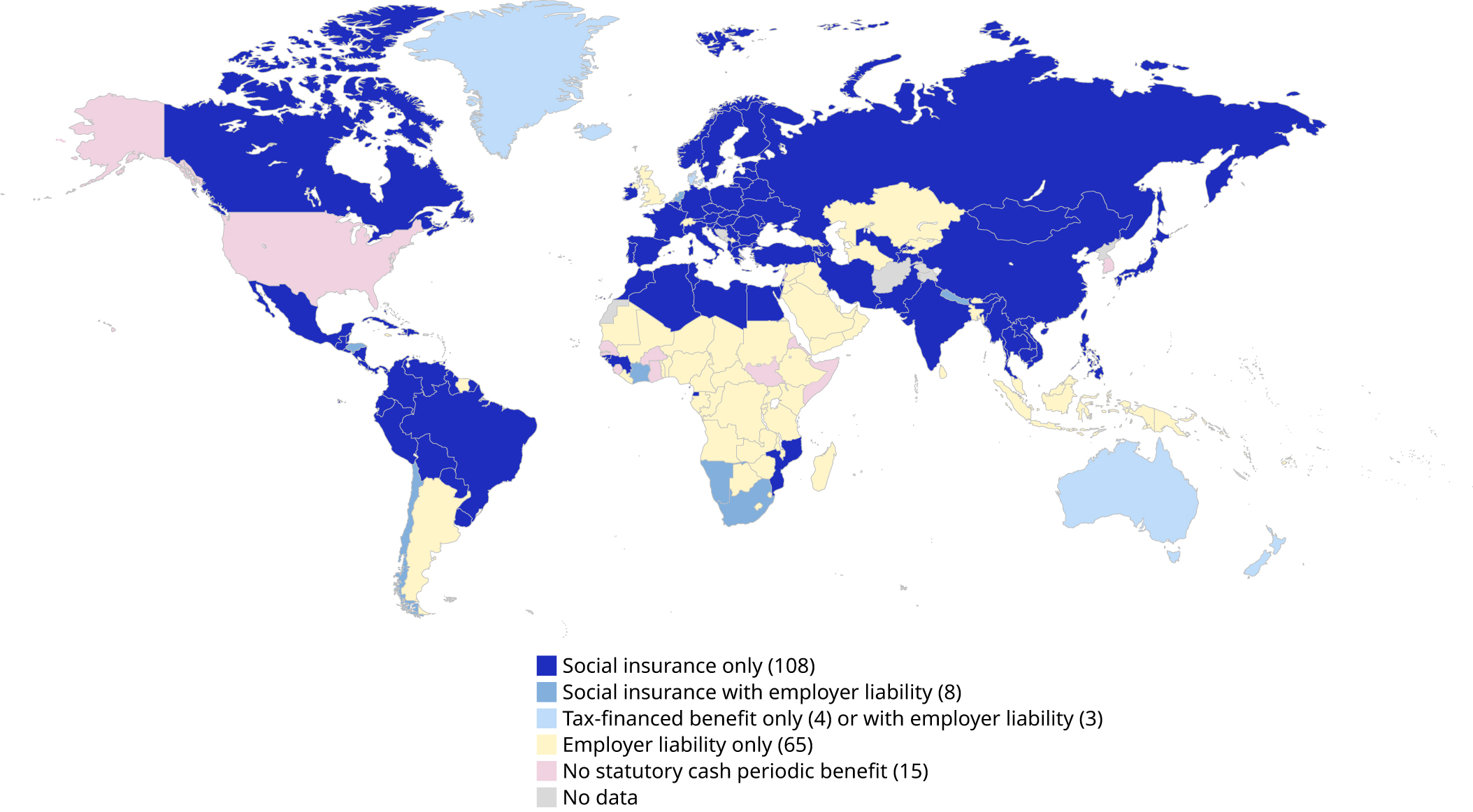

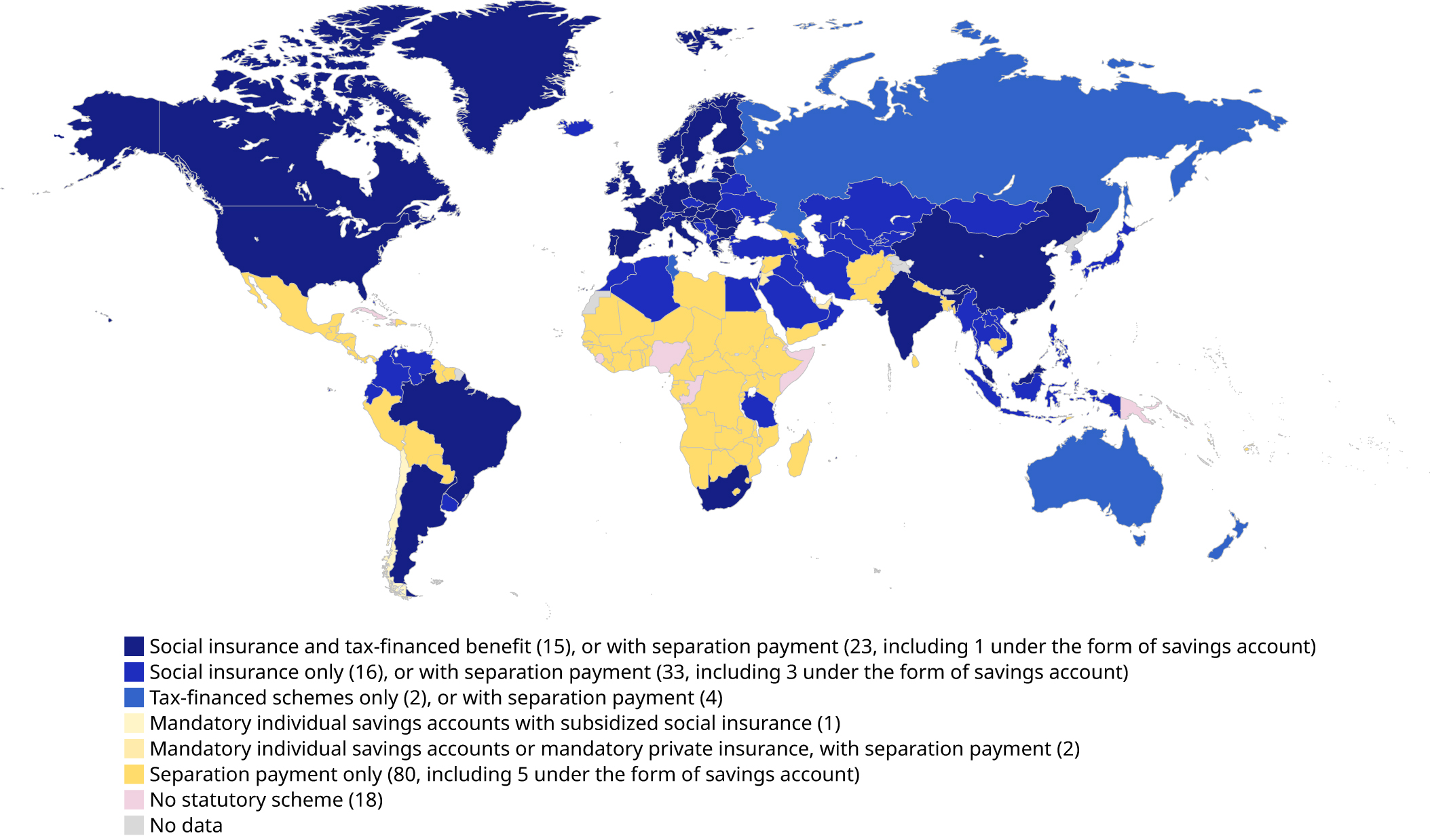

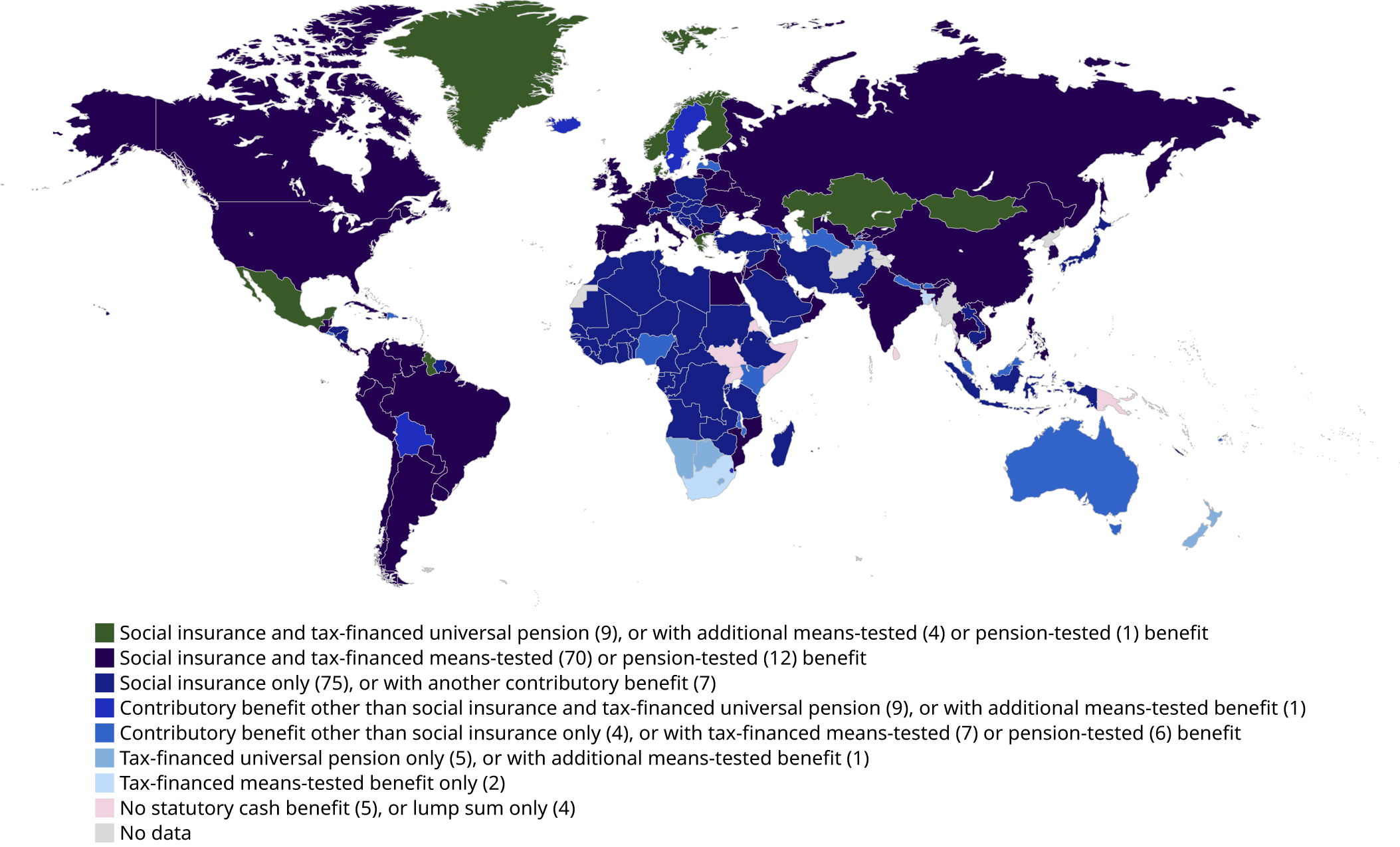

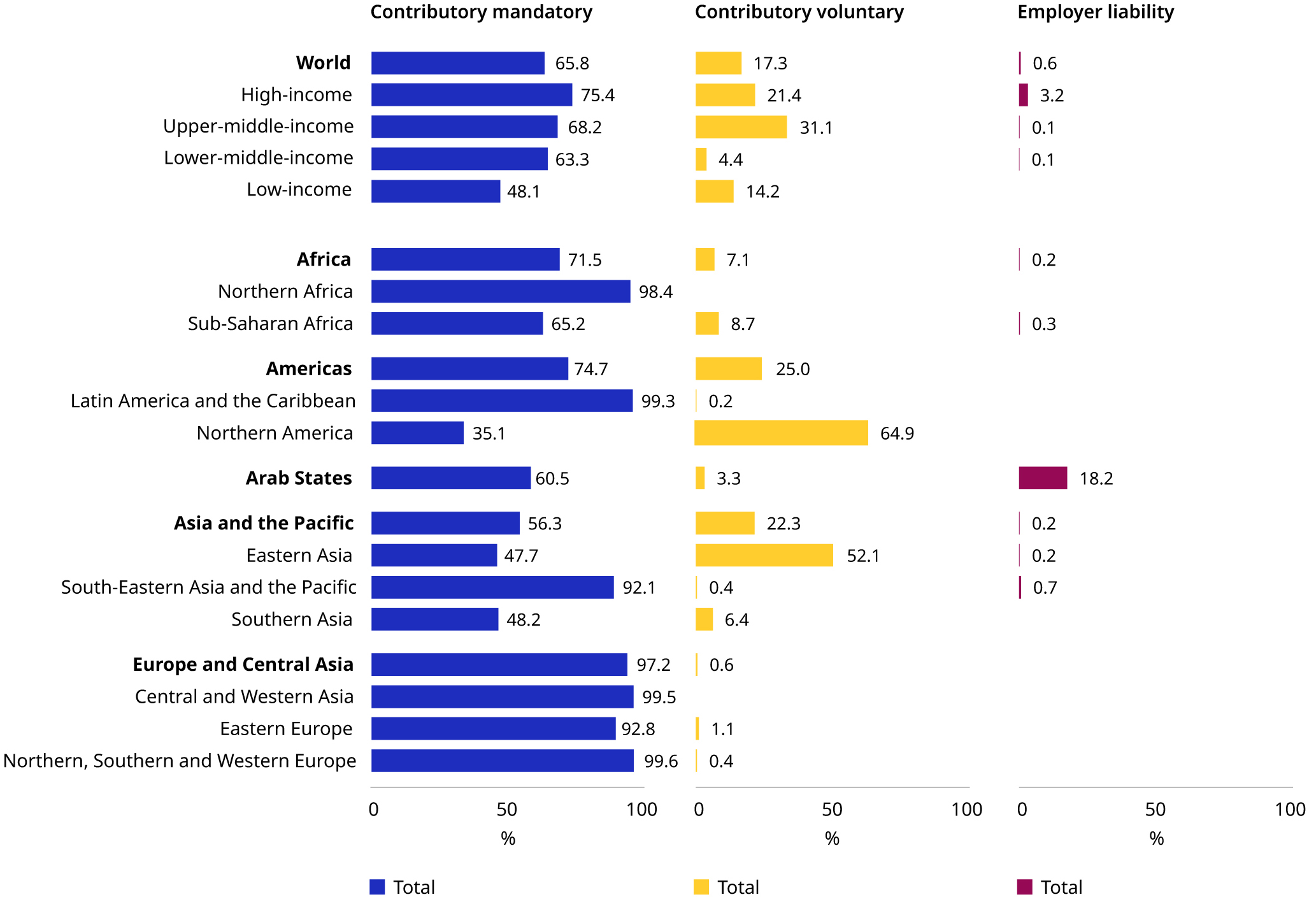

As of 2024 (see figure 4.1), more than two thirds (145) of the 213 countries or territories for which data is available provide statutory child or family benefits. However, non-statutory programmes may still exist in other countries. Recent child benefit reforms show further progress (see table 4.1). Of the countries or territories with statutory periodic child or family benefits, the latest analysis of legal coverage indicates the following schemes operating worldwide:

-

tax-financed universal or quasi-universal child benefits: 58;

-

contributory schemes only: 29;

-

contributory and tax-financed means-tested schemes (non-universal): 11;

-

tax-financed means-tested schemes only: 47.

Schemes anchored in national legislation are usually more stable in terms of financing and institutional frameworks, and provide legal entitlements to eligible individuals and households, thereby guaranteeing protection as a matter of right. Other schemes include at-scale non-statutory, non-contributory programmes operating elsewhere (see section 3.1, ILO and UNICEF 2023). Other programmes providing cash or in-kind support to children in need exist, which are often limited to certain regions or districts and are generally designed with the objective of reducing poverty. Others exist as a response to humanitarian crises or other non-typical circumstances. These are provided through the government, and/or supported by United Nations agencies, development partners, non-governmental organizations or charities.

Figure 4.1 Social protection for children and families (cash benefits) anchored in law, by type of scheme, 2024 or latest available year

Disclaimer: Boundaries shown do not imply endorsement or acceptance by the ILO. See full ILO disclaimer.

Note: The universal child benefit count is higher than indicated in previous editions of the World Social Protection Report, owing to the inclusion of several territories. The number in parenthesis refers to the count of countries or territories.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources.

Table 4.1 Child social protection reforms, selected countries, 2021–24

|

Country |

Year |

Adopted or planned measure |

|

Brazil |

2023 |

New supplement in Bolsa Família for children under 6 years old. The Benefício Primeira Infância was introduced to supplement the Bolsa Família with an additional 150 Brazilian reais (US$28) paid each month to 8.9 million children aged 0 to 6 (Government of Brazil 2023b). |

|

Libya |

2021 |

Reactivation of universal child benefit for children under 18 years old. Libya effectively reintroduced its universal child benefit which had been suspended since 2013. A monthly benefit of 100 Libyan dinars (US$20) is paid for all Libyan children aged 0 to 18. |

|

Montenegro |

2022 |

New universal child benefit for children under 18 years old. The Government introduced a universal child benefit for children aged 0 to 18 at the end of 2022. A flat rate monthly benefit of €30 (US$32) is paid for each child. |

|

Oman |

2023 |

New universal child benefit for children under 18 years old. The Government introduced a universal child benefit in 2023 as part of a major reform of its social security system (ILO 2023h). A flat rate monthly benefit of 10 Omani rials (US$26) is paid for each child. |

|

Republic of Korea |

2022 |

Extension of age-limited quasi-universal child benefit, now for children under 8 years old. A quasi-universal child benefit for children aged 0 to 6 was introduced in 2018, extended to children aged 0 to 7 in 2019, and subsequently to children aged 0 to 8 in 2022. A monthly benefit of approximately 100,000 won (US$73) is paid for each child. |

Sources: Based on ILO and UNICEF (2023); ILO, UNICEF and Learning for Well-Being Institute (2024) and information from national sources except where indicated otherwise.

The importance of school feeding

School feeding programmes provide meals (including take-home rations) to school-age children and adolescents. They are critical for child well-being (see box 4.3). Currently, 418 million children worldwide receive free or subsidized daily school meals (WFP 2022). According to WFP (2022), there has been a global increase in government-led school feeding programmes, signifying heightened governmental commitment across different economic levels from 2020 to 2022, with the percentage of countries with school feeding policies increasing from 79 per cent to 87 per cent. This expansion has also created approximately 4 million direct jobs across 85 countries (WFP 2022). School feeding programmes also serve as comprehensive integrated programmes with over 80 per cent of countries incorporating complementary health and nutrition activities, reinforcing their pivotal role in promoting schoolchildren’s well-being.

Combining cash benefits and access to key services and information

Access to cash benefits and childcare services yields multifaceted effects on social mobility, family income and educational outcomes, and reduces deprivations. Recent research indicates enduring effects, particularly in early childhood care and education investments, resulting in sustained growth of family income by increasing women’s labour force participation, and improved life trajectories. Despite the positive impact of cash benefits, the limitations of cash alone are evident, emphasizing the need for complementary interventions to overcome non-financial and structural obstacles (Learning for Well-Being Institute, 2024). “Cash plus” programmes, which integrate cash benefits with other interventions, address multifaceted challenges and maximize transformative potential (UNICEF, Heart and UKAID 2022). Ensuring universal access to health and other services without hardship is also of critical importance for maximizing and sustaining the impacts of cash benefits. It is an essential component of child-sensitive social protection systems (see section 4.4). The role of social workers in promoting children’s well-being is key to connecting them with critical social services by challenging harmful norms that violate children’s rights.

Box 4.3 The role of school feeding in addressing poverty, socio-economic vulnerabilities and supporting adaptation to the climate crisis

|

School feeding programmes can contribute to ensuring children’s development – including nutrition, health and education (Sanfilippo, de Neubourg and Martorano 2012) – and foster long-term social and economic development. By providing a consistent supply of essential nutrients to children, they enhance human capabilities and generate savings equivalent to 10 per cent of the income for economically disadvantaged households – and even more for take-home rations (Bundy et al. 2018). They also help address the global food crisis and promote climate-smart and sustainable food systems. The estimated US$48 billion annual investment in these programmes offers a significant market for food producers, enabling the transformation of food systems and the increased sustainability of diets (WFP 2022). Homegrown school feeding programmes (Tette and Enos 2020) are integral to this transformation. They can support smallholder farmers (especially rural women and indigenous producers) by purchasing more local food, which increases local agro-biodiversity and strengthens local food security (Hunter, Martínez-Barón and Loboguerrero 2022). School meals programmes can help transform food systems through planet-friendly policies, delivering significant benefits for child health and wider society (Pastorino et al. 2023). In Armenia, solar power systems were installed in five schools and farms. The surplus electricity generated was sold back to the grid, and funds reinvested in school feeding programme and other social services. This stabilized farm produce demand and supply, and reduced food losses, electricity bills and carbon emissions. While there has been progress in expanding school feeding, challenges persist, particularly in low-income countries, with 73 million children still going to school hungry. Although these countries have increased domestic funding for school meals – from 30 per cent to 45 per cent between 2020 and 2022 – international support has declined (WFP 2022). Addressing this challenge requires a concerted effort from development actors. Closing the funding gap in low-income countries presupposes exploring innovative financing models like debt-for-school-meal swaps and support from development partners and international financial institutions. Ultimately, as countries continue to refine their social protection strategies, recognizing the inherent linkages with school feeding will be essential for ensuring child well-being. |

Tackling inequality from the start for girls and young women

Making social protection for children more gender-responsive focuses on how social protection can:

-

address gender-specific risks – that is, premature withdrawal of girls from school, gender-based violence, child marriage and forced labour, unpaid care work and discrimination against girls and young women; and

-

support sexual and reproductive rights for adolescents.

It also centres on how the presence and care needs of children in households impact the welfare and development of adolescent girls, and the labour force participation and autonomy adult women and mothers – including women with multiple and intersecting vulnerabilities, such as women with disabilities, from ethnic minorities or from rural areas (Razavi et al., forthcoming a).

Social protection systems are an essential mechanism for realizing children’s rights and can act as a powerful policy tool for the empowerment of girls and young women, particularly through gender-transformative approaches. This rights-realization and empowerment function can be especially pertinent for girls who, from the outset, experience gender inequalities in all its forms.

However, social protection for children remains woefully low and inadequate and much more needs to be done to enhance its gender-responsiveness (Razavi et al., forthcoming a). Social protection must work for girls and women, and address structural gender inequalities. This means getting the basics right: closing protection, comprehensiveness and adequacy gaps. But it also requires gender-based increments as affirmative action, supporting the development of young women’s capabilities – through age-extended child benefits, quality education and training opportunities – and access to sexual and reproductive health services.

Child benefits are not automatically “empowering” for mothers and women. For instance, conditional cash transfers can involve high transaction costs for women and some contributory family benefit schemes carry direct legal exclusion and differentiated and unequal treatment for men and women. Thus, child benefit design must support women’s engagement in formal employment. This presupposes accessible, affordable and quality social services and care services, which could be an area of decent job creation. Employers can help by adopting family-friendly policies (such as flexible working times, breastfeeding breaks and telework) to help working parents share work–care responsibilities. Enforcing compliance with child maintenance support payments would also help single parents, who are mostly women (Razavi et al., forthcoming a).

Enhancing adaptation and the responsiveness of social protection for children to climate shocks

Getting the basics of social protection right and reducing vulnerability ex ante is key for contending with the climate crisis. This presupposes having a comprehensive social protection system in place, providing adequate benefits to a large part of the population as part of an integrated set of social and climate action policies. Adaptation to the climate crisis implies benefit design and institutional capacity which allow for rapid extension, top-ups and advanced payments, and reaching children in remote locations.

Further adaptation could be made to increase shock responsiveness through adjustments and a systems-wide approach (see Chapter 3). For instance, when combined with disaster risk management approaches, this could mean additional or higher payments are triggered by metrological authorities when thresholds are passed (for example, too cold or hot, or flooding). For instance, UNICEF Bosnia and Herzegovina has supported a subnational shock-responsive social protection model which provides additional cash support for flood-affected children (UNICEF, forthcoming).

Given that climate risks impact the whole family, any protection designed to address a family’s resilience should take into account factors such as family size and specific risks such as child labour or child marriage. It should also address consumption needs, enhance asset building through in-kind support (such as drought-resistant crops), boost productivity by increasing parents’ access to decent work and higher earnings, and increase opportunities for diversified earnings and work opportunities. The latter requires social protection to help facilitate the transition of caregivers from sectors affected by climate mitigation policy (for example, brown-to-green) to unemployment support, or from high climate risk sectors of agriculture to less-affected agriculture sectors. This diversification of earnings promotes income security and resilience.

The removal of fossil fuel subsidies can expand fiscal space for child benefits whilst also contributing to wider climate change mitigation policies. Fossil fuel subsidies run counter to mitigating global heating and are often regressive. There has been growing interest in exploring how fuel subsidy reform frees fiscal space for social protection (section 2.1). There is also promising evidence that reforming subsidies would reduce child poverty. For example, simulations for converting Tunisia’s energy subsidy found that a universal child benefit would be both more progressive and more efficient in reducing poverty (Bouzekri and Orton 2019). Moreover, in 2010, the Islamic Republic of Iran cut its fuel subsidy and converted it into a quasi-universal basic income. Today, this effectively functions as an affluence-tested child benefit with a high coverage of 86.8 per cent (Kishani Farahani, Ali Khan and Orton 2019).

Furthermore, some countries are recognizing the need to offset the cost of greenhouse gas emission mitigation policies like carbon pricing. For instance, Canada’s Climate Carbon Rebate2 is a modest tax-free supplemental payment paid to families with children through the Canadian child benefit – approximately US$41–75 per quarter for one child, with increments for each additional child.

Recent experience also shows how national child benefit systems can function as powerful shock-responsive mechanisms and can be extended to protect children displaced by crises. The international response to the war in Ukraine shows how well-developed systems are inherently shock-responsive. Millions of displaced Ukrainian children were accommodated by OECD systems, and given access to national child benefits. Other promising examples are demonstrated by the Brazilian Government which has granted access to its flagship cash transfers for vulnerable and displaced Venezuelan families (ILO and UNICEF 2023). However, as section 4.1.3 shows, too many children remain uncovered and are not adequately protected against ordinary child life course risks or various crises.

A major push for universal child benefits

As social protection coverage for children slowly increases, momentum has gathered behind universal child benefits as a foundational policy for maximizing social protection coverage for all children. Recent evidence shows also how universal child benefits can effectively reduce absolute and relative income child poverty, while also acting as the foundation of a child-sensitive social protection system to unlock human capabilities for social and economic development and inclusive growth (ILO, UNICEF and Learning for Well-Being Institute 2024).

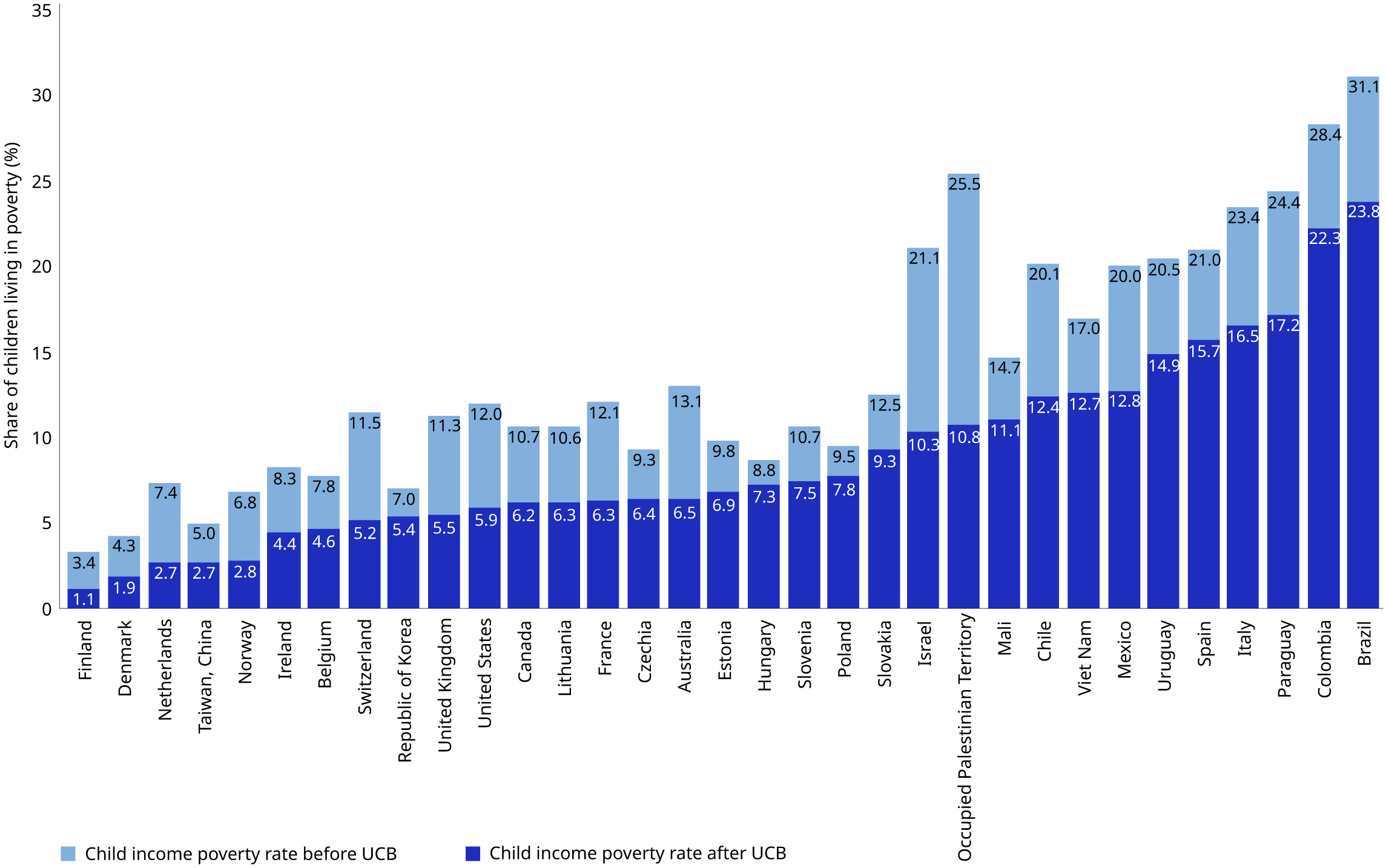

Figure 4.2 Simulated effects of universal child benefits (UCB) on child income poverty, selected countries and territories, latest available year (percentage)

Notes: Relative child income poverty rates are calculated as the proportion of children living in households on incomes of less than 60 per cent of the median household income in the population. Household incomes are adjusted for comparison using the square root of the household size. These estimates are calculated on the assumption that all households take up the benefit.

Source: ILO estimates based on the LIS Database(multiple countries).

Figure 4.2 introduces a simulation of the effects of universal child benefits on child poverty in 33 countries and territories. The simulated estimates are calculated based on both the design of the policy (the delivery of a flat cash transfer for all children aged 0 to 18) and a benefit amount equivalent to the average payment per child per month in the 29 countries worldwide that presently provide universal child benefits (6 per cent of the average wage). The combined light and dark blue bars show relative child income poverty without a universal child benefit (and include the effects of any existing child social protection policies in place). The dark blue bars represent the relative child income poverty rate with a simulated universal child benefit policy (replacing payments for any existing child benefits). The light blue bars represent the decrease in poverty that could be achieved by a universal child benefit.

The results show that, in every country, a universal child benefit could reduce poverty more substantially than existing child policy efforts. The extent of the effect varies, with higher reductions in poverty in countries with higher pre-existing child poverty risks, and lower reductions in countries with pre-existing rates of around or below 10 per cent. Countries with universal child benefits already in place – such as the Nordic countries – have lower poverty rates overall; yet, increases in adequacy will improve anti-poverty effects overall.

On average across these countries, universal child benefits could reduce poverty by 5 percentage points, equivalent to a reduction of 39 per cent in the number of children experiencing poverty. In recent years, several countries have adopted universal child benefits, and many more are exploring the option (see table 4.1). Evidence would suggest that universal child benefits are a simple and effective way to address the dual challenge of maximizing social protection coverage for children, while addressing the persistent challenge of child income poverty risks.

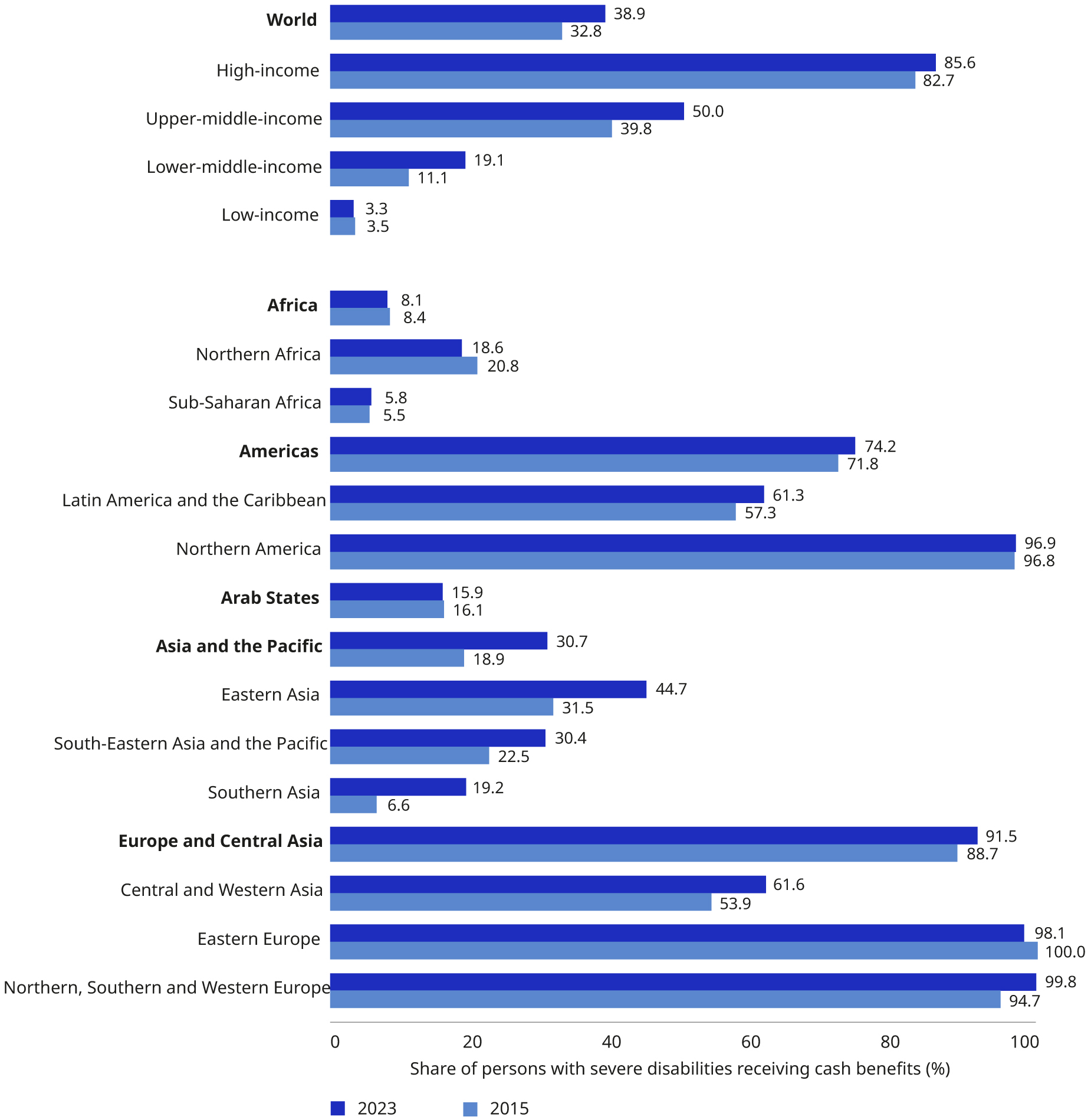

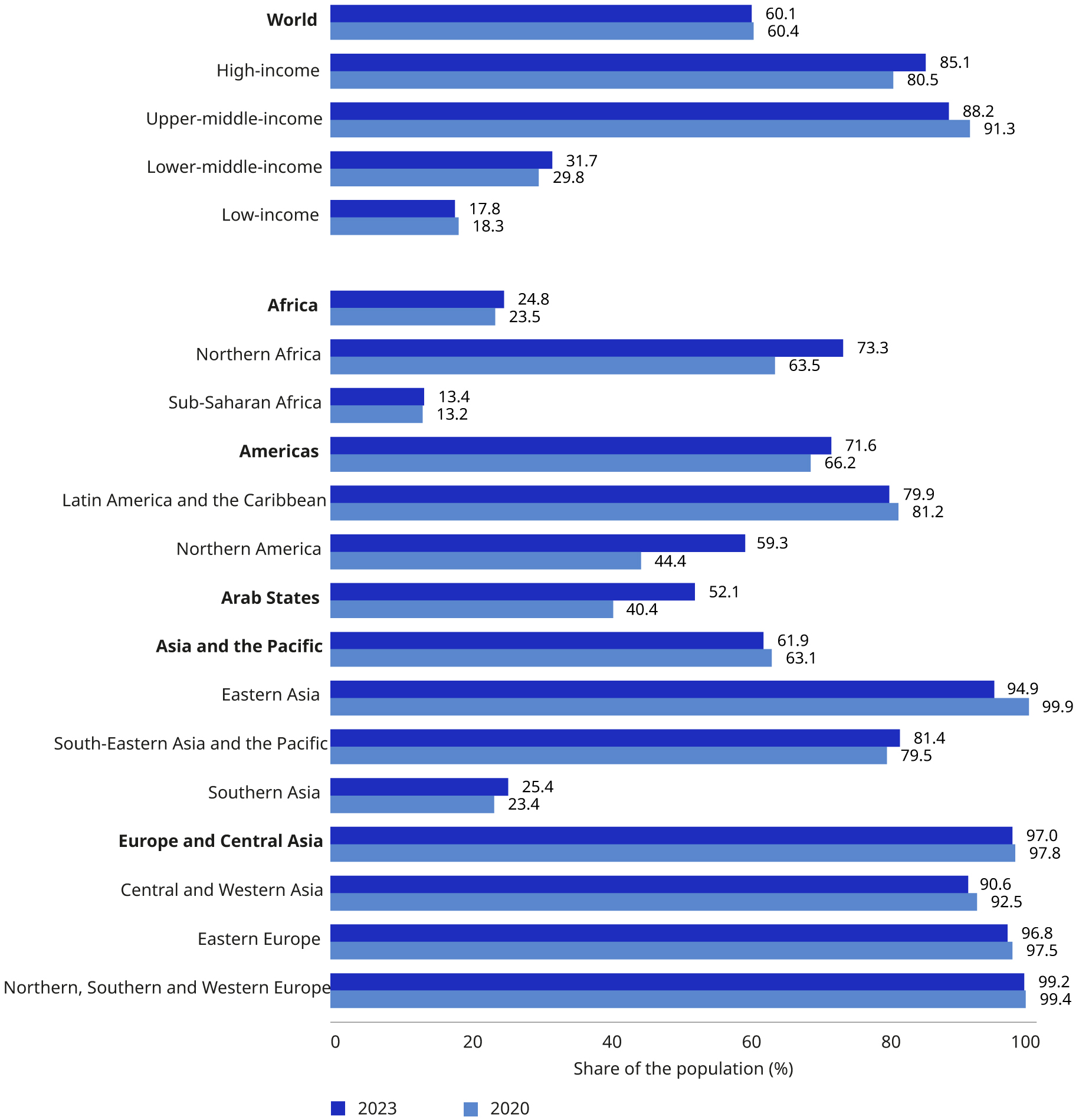

4.1.3 The state of effective coverage for children

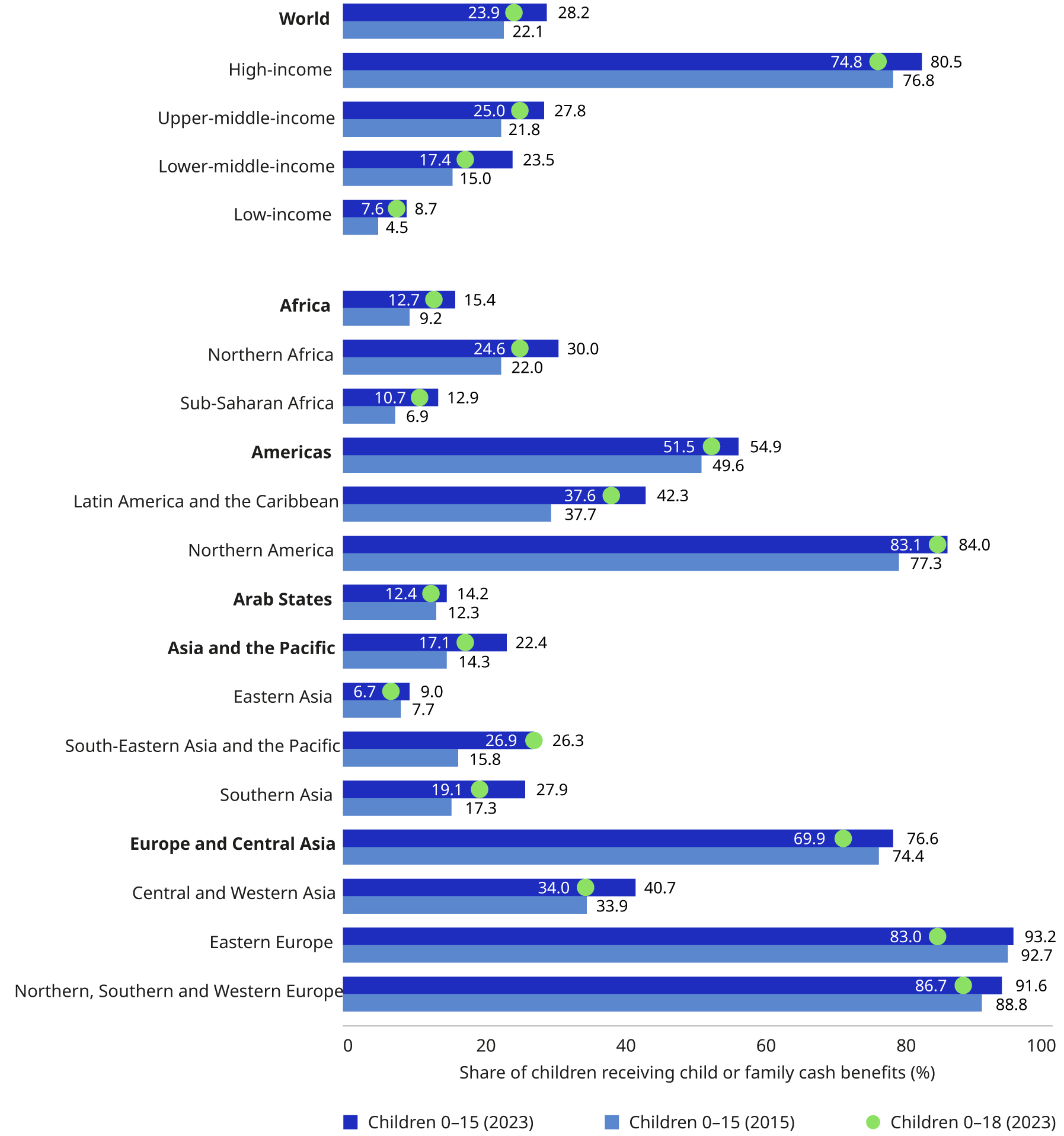

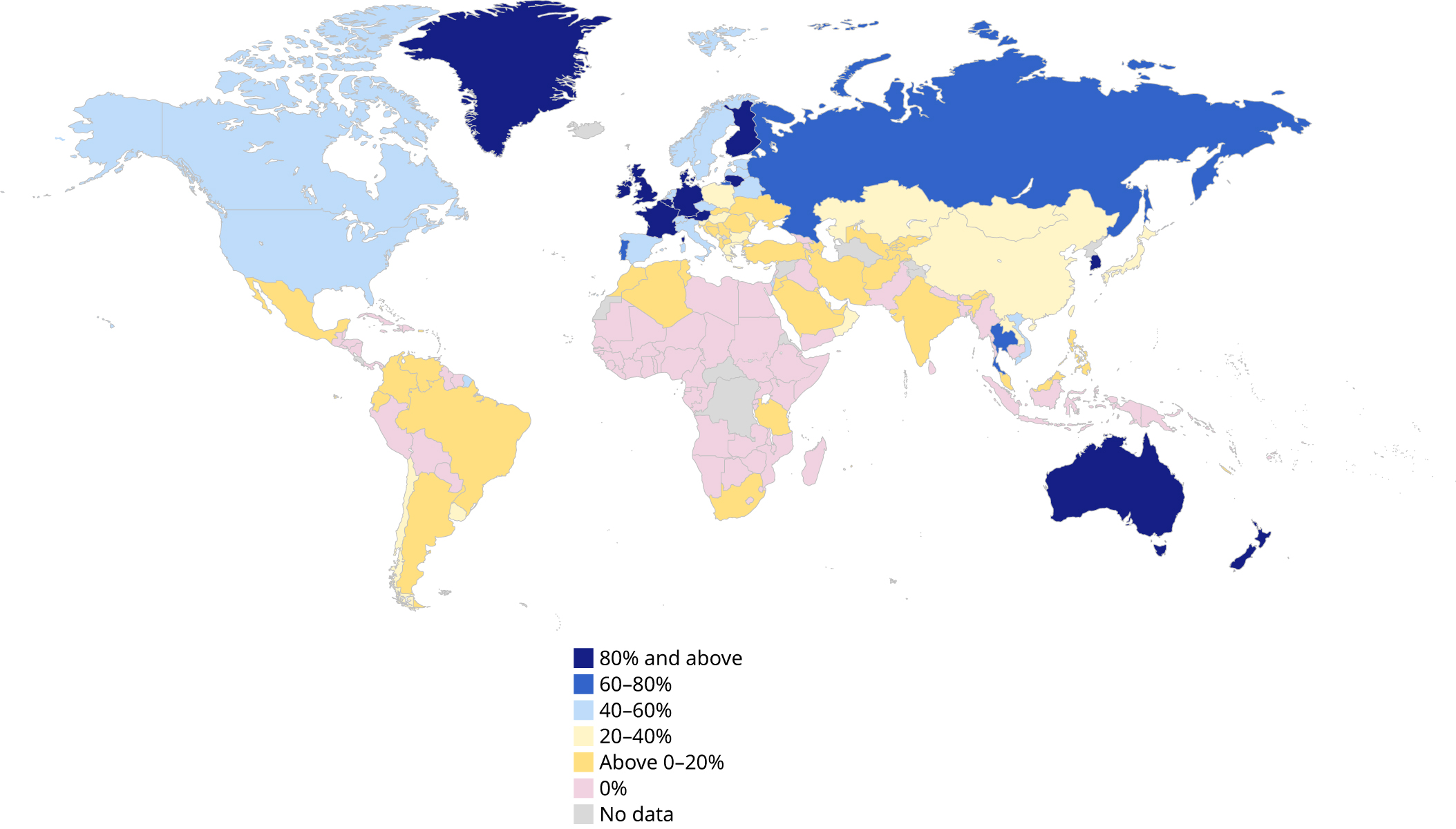

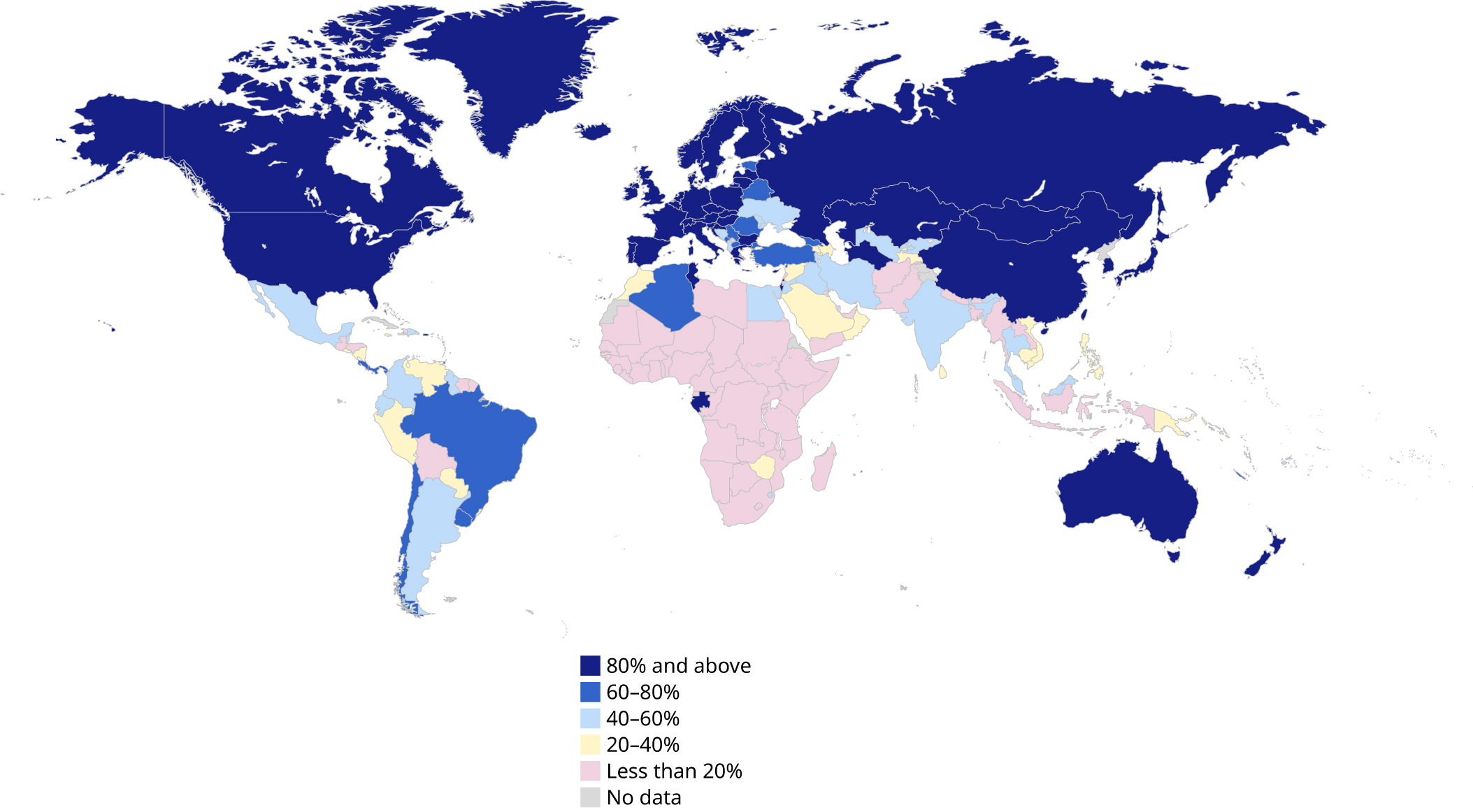

Current data on effective coverage indicate that only 23.9 per cent of children aged 0 to 18 are covered (see figure 4.3).3 This means the vast majority of children – 1.8 billion under 18 years old – are not covered. And fewer than one in ten (7.6 per cent) in low-income countries receive a child or family cash benefits, leaving millions vulnerable to missed education, poor nutrition, poverty and inequality, and exposing them to long -lasting impacts.

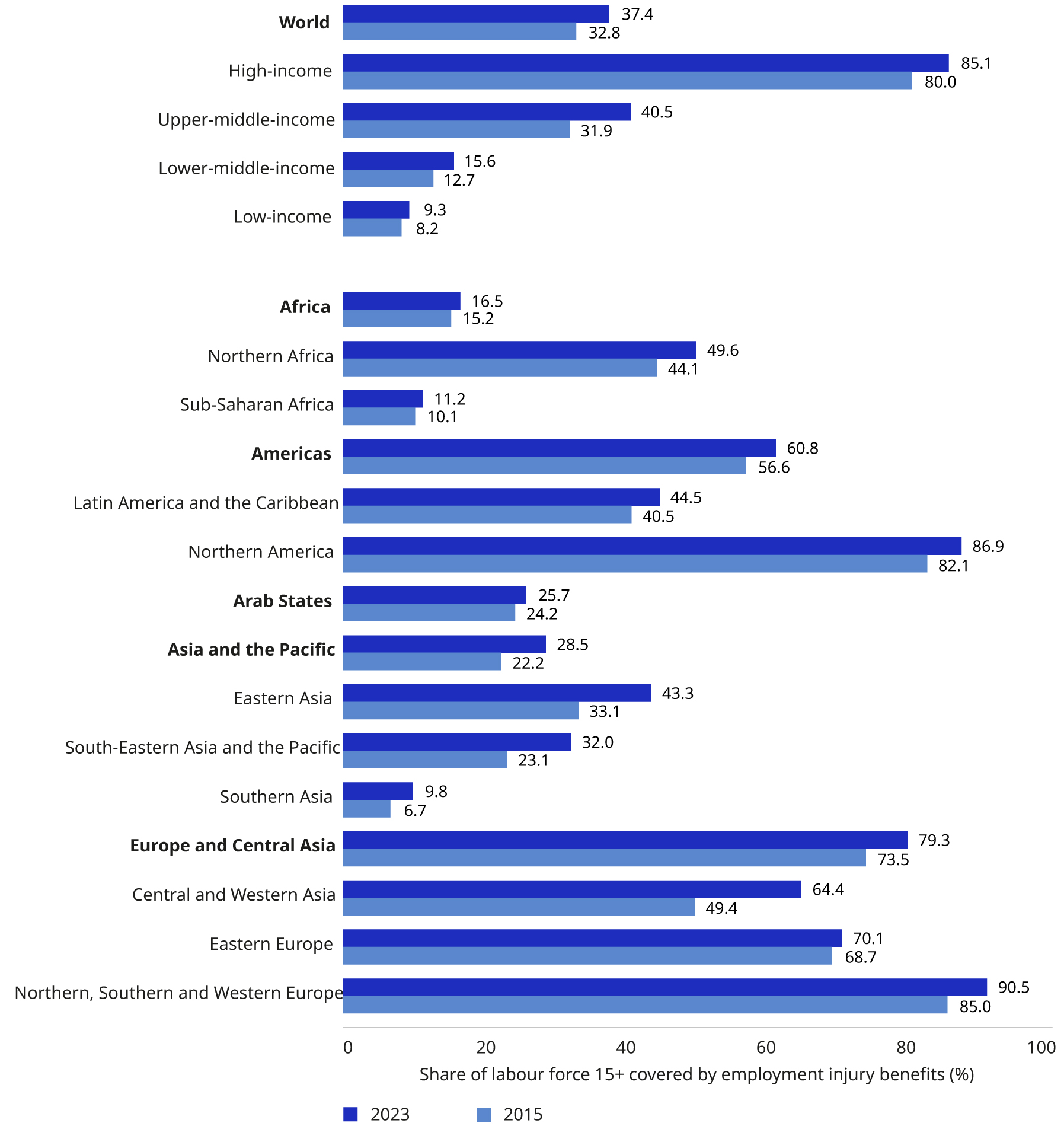

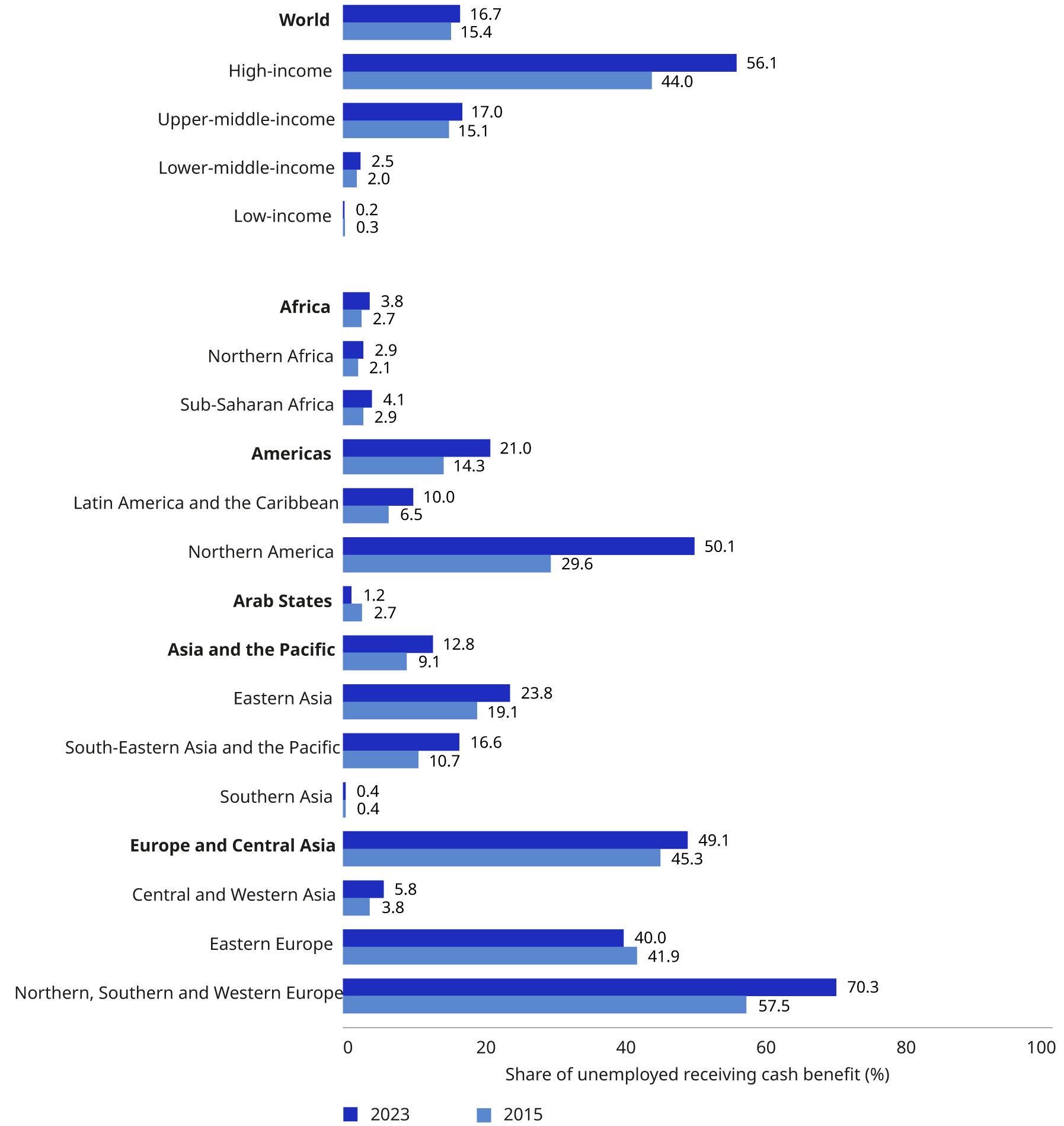

The proceeding trend data on effective coverage discussed below is currently available only for children aged 0 to 15. This data shows that, since the adoption of the SDGs in 2015, there has been a modest global increase in child benefit coverage, from 22.1 per cent in 2015 to 28.2 per cent in 2023.

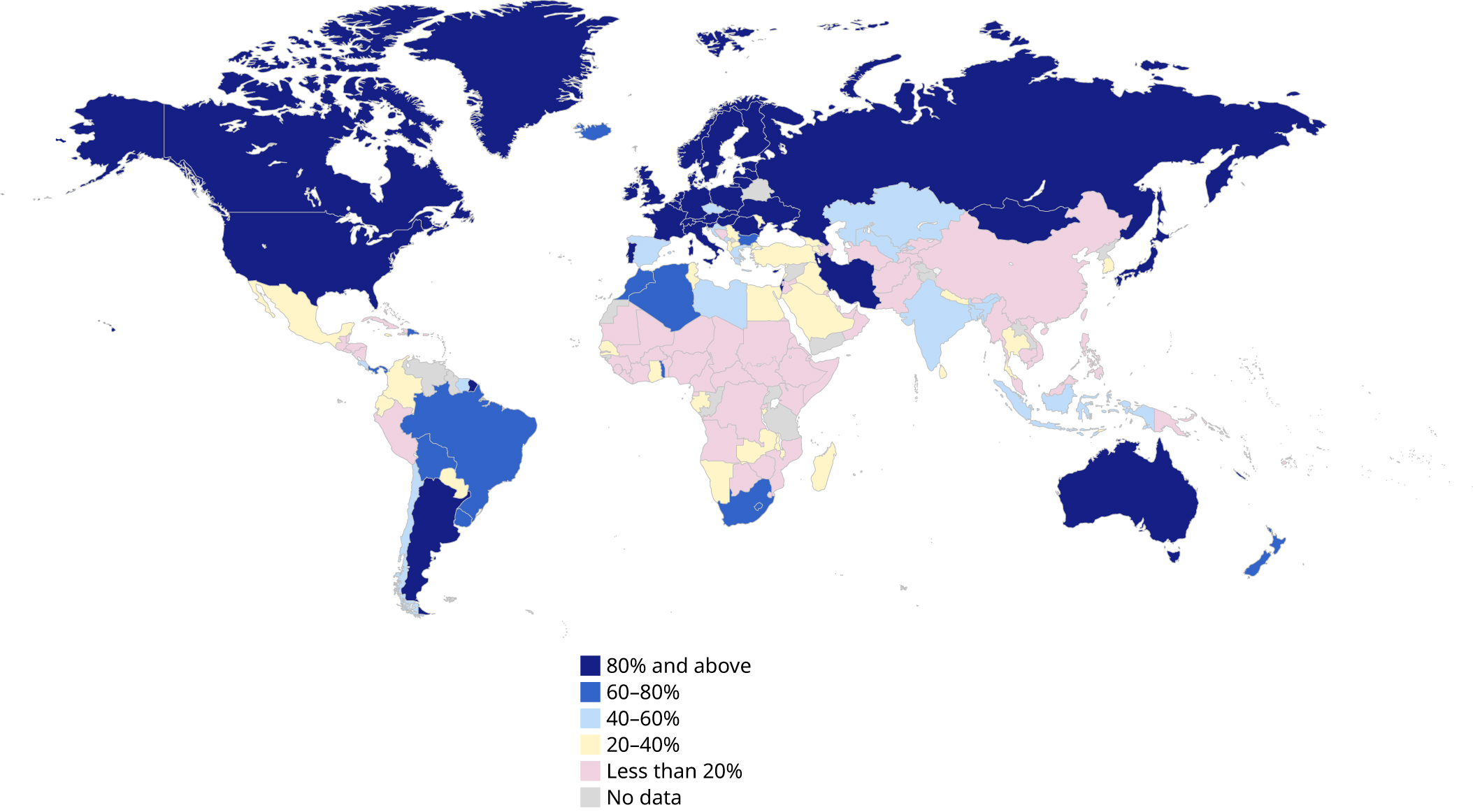

Significant regional disparities continue to exist (figures 4.3 and 4.4). Effective coverage rates vary greatly across regions, and the same is true for improvements in coverage since 2015. In the Arab States, rates increased from 12.3 per cent to 14.2 per cent. In Europe and Central Asia, coverage has increased slightly from 74.4 per cent to 76.6 per cent. The Americas saw a more marked improvement, with rates increasing from 49.6 per cent to 54.9 per cent. In Africa, coverage has increased, from 9.2 per cent to 15.4 per cent. Asia and the Pacific experienced the largest increase from 14.3 per cent to 22.4 per cent. However, this progress should not detract from the fact that Africa and Asia and the Pacific still have enormous absolute numbers of children – 492.8 and 764.8 million, respectively – who remain uncovered.

In low-income countries, rates have increased from 4.5 per cent in 2015 to 8.7 per cent in 2023. While progress has happened, it is too slow and remains woefully insufficient. Low-income countries continue to be affected by protracted humanitarian crises and are on the front line of climate breakdown, locking children in a perpetual cycle of poverty. For the same period, lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income countries have made much more substantial progress, with coverage increasing from 15.0 per cent to 23.5 per cent and from 21.8 per cent to 27.8 per cent, respectively. High-income countries continue to edge closer to attaining universal coverage, with rates increasing from 76.8 to 80.5, yet still leaving one in five children uncovered.

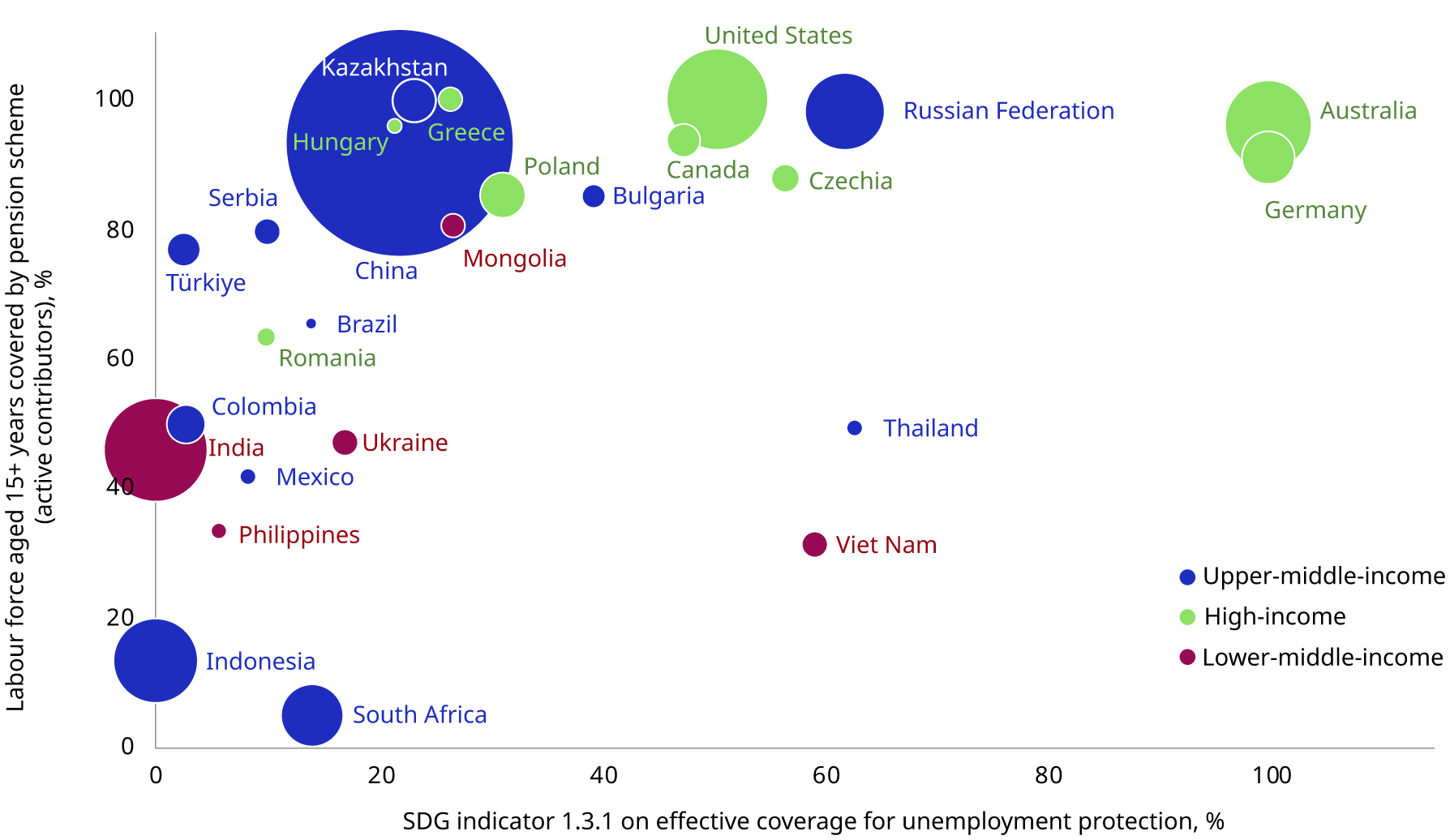

The children least covered are those most susceptible to climate risks. Analysis shows that coverage rates for children in countries highly vulnerable to climate change are a third lower than those in countries not classified as being at high risk (ILO, Save the Children and UNICEF 2024).

Figure 4.5 by quadrant shows that all but one of the low-income countries experience high climate risk and low social protection coverage (top left). The majority of lower-middle-income countries are also found in this area. This patterning highlights a double concern for child poverty and inequality, both within and between countries, as social protection is least available in parts of the world where it is most needed.

Figure 4.3 SDG indicator 1.3.1 on effective coverage for children and families: Share of children receiving child or family cash benefits, aged 0 to 15 (2015 and 2023) and aged 0 to 18 (2023), by region, subregion and income level (percentage)

Notes: See Annex 2 for a methodological explanation. Data for coverage of children aged 0 to 18 is available for 2023 only. Global and regional aggregates are weighted by population aged 0 to 15 and 0 to 18. Estimates are not strictly comparable to the previous World Social Protection Report due to methodological enhancements, extended data availability and country revisions.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates, 2024; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources.

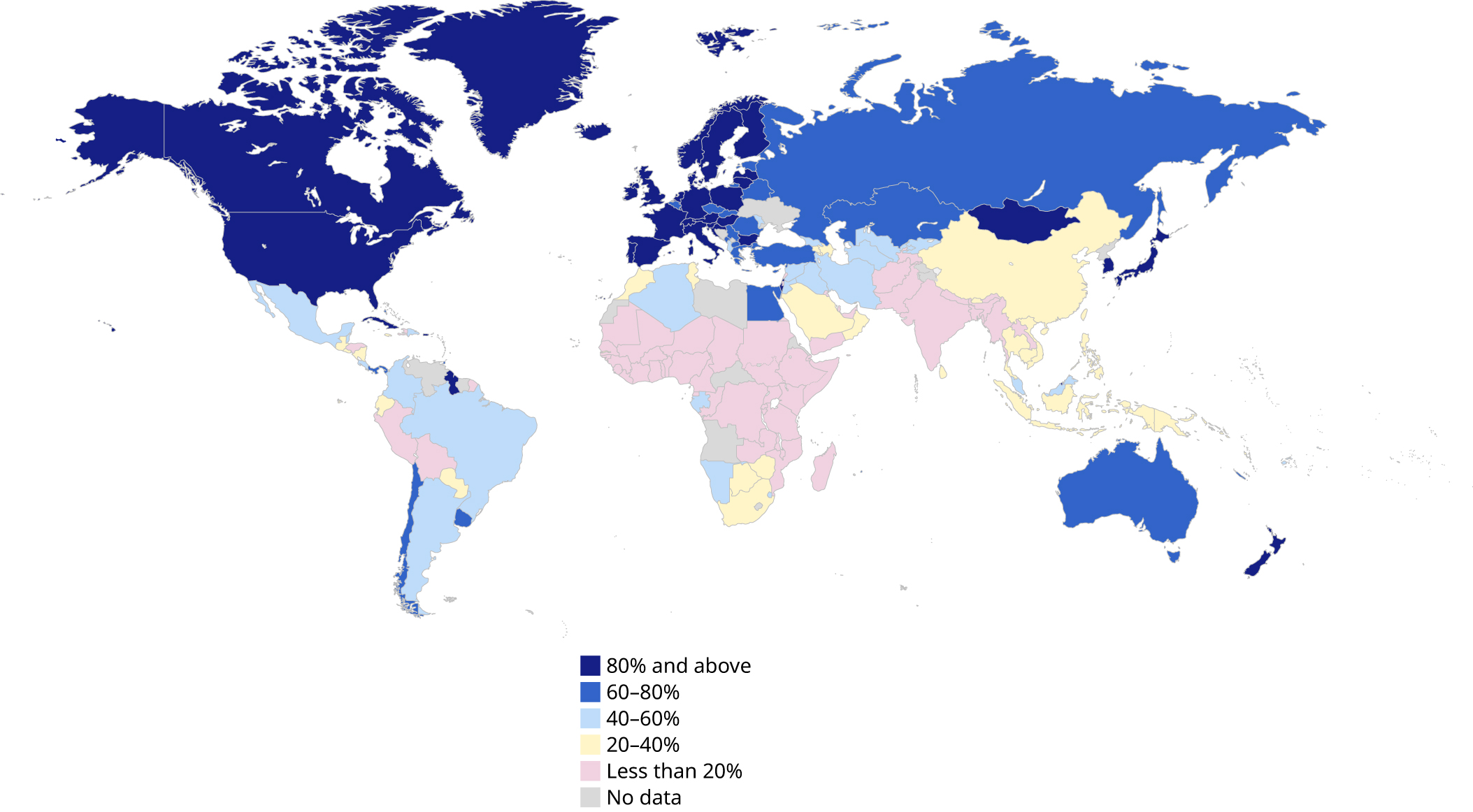

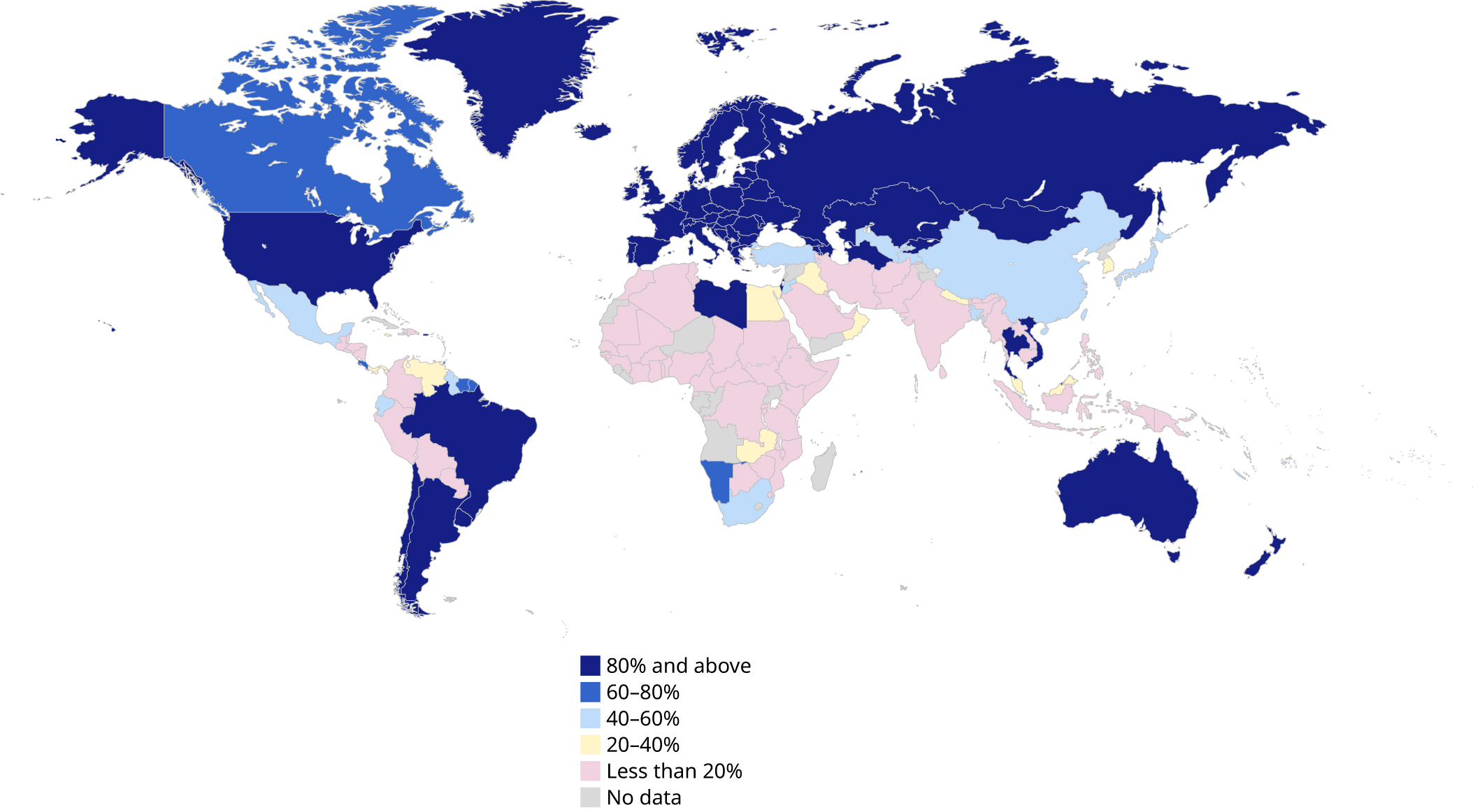

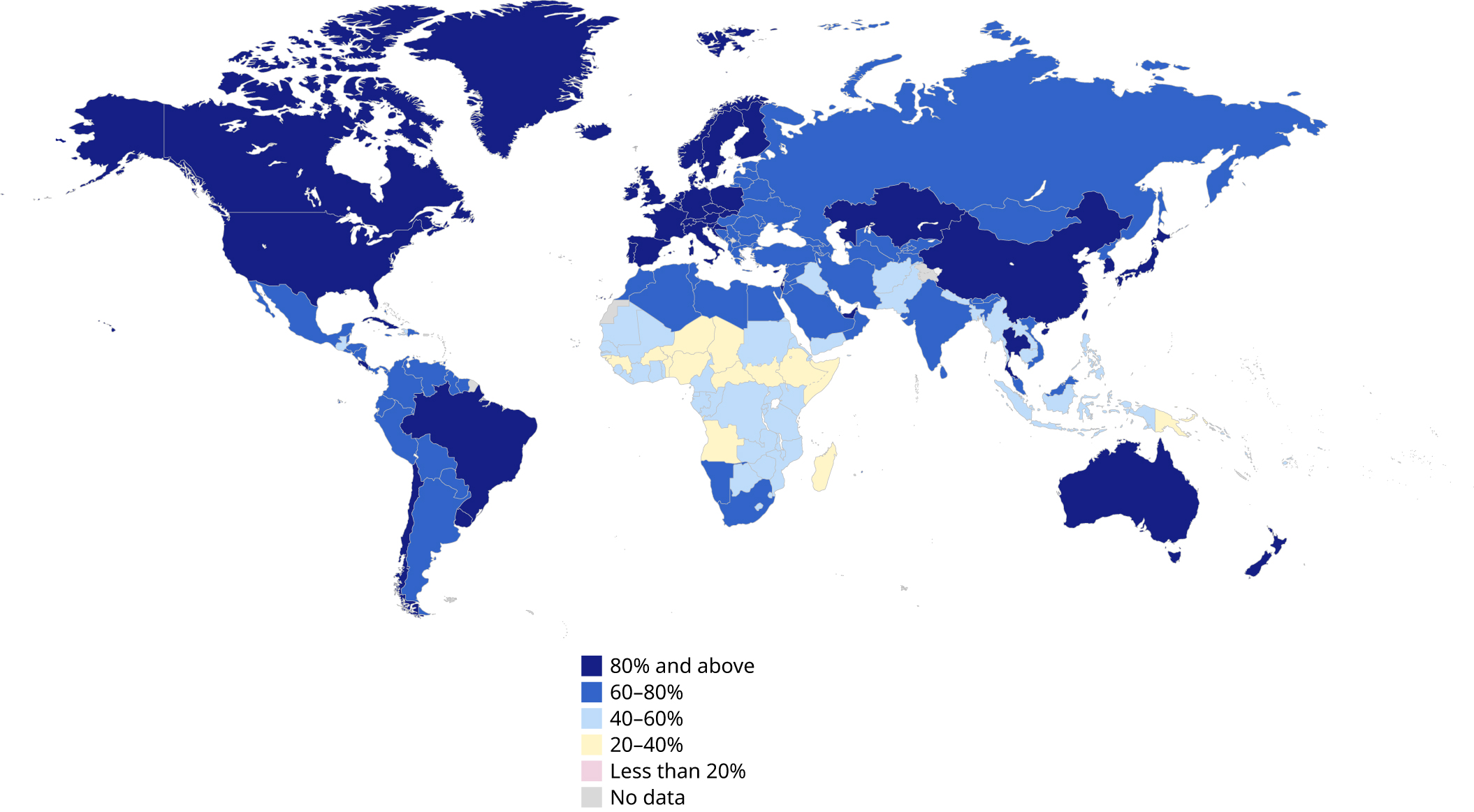

Figure 4.4 SDG indicator 1.3.1 on effective coverage for children and families: Share of children aged 0 to 15 receiving child and family cash benefits, 2023 or latest available year (percentage)

Disclaimer: Boundaries shown do not imply endorsement or acceptance by the ILO. See full ILO disclaimer.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources.

Figure 4.5 The Children’s Climate Risk Index compared with effective coverage for children and families: Share of children aged 0 to 15 receiving child or family cash benefits, by income level, 2023 (percentage)

Source: Children’s Climate Risk Index, UNICEF (2023b) and ILO estimates, World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ILOSTAT; national sources.

4.1.4 Adequacy of social protection for children

Benefits should be enough to meet the stated goals of schemes (such as contributing to child-raising costs and nutrition goals). They should also be enough to meet the goals of the international social security standards – which stress the importance of adequacy – and their key principles which should inform the design and implementation of every social protection benefit, including regular indexation. Even when countries meet this specified minimum, where fiscal space permits, they should consider higher levels of expenditure on children – Convention No. 102 sets a minimum floor, not a ceiling. The ILO’s Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations has also recently stressed the importance of more appropriate benchmarks, as benefit levels remain too low in many countries (ILO 2023d). This might imply the need for a higher international social security standard for the branch of family and child benefits.

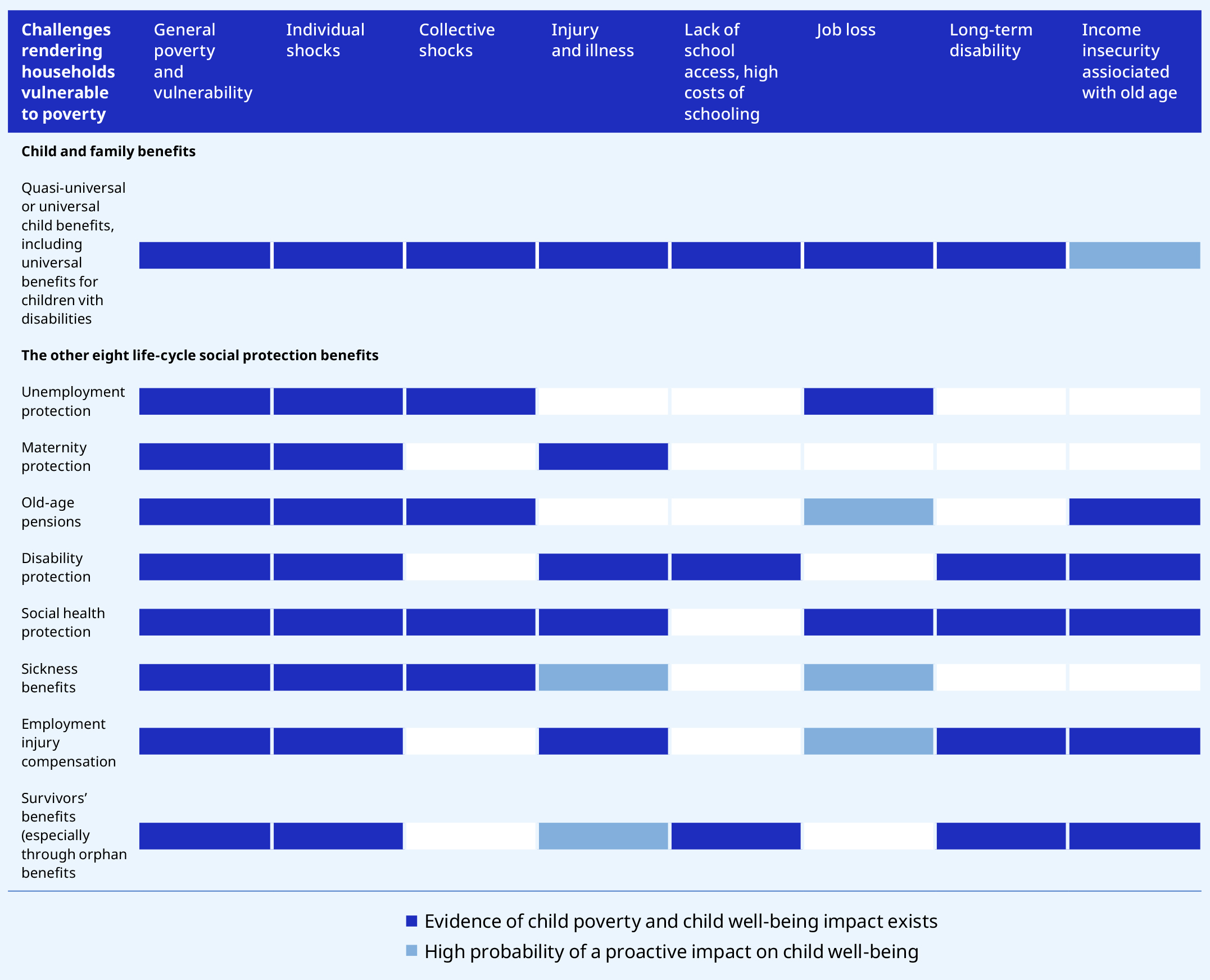

Figure 4.6 Impact evidence of how child poverty and vulnerability risks are addressed through the nine life-cycle social protection functions

Note: Authors’ interpretation of findings from the sources cited below.

Sources: ILO (2011b); Bastagli et al. (2016); Davis et al. (2016); ODI and UNICEF (2020) 2020; Richardson (2015); Standing and Orton (2018).

Adequacy also requires countries to ensure that benefits are set at the right level for diverse family circumstances, taking into account age, family size, family structure and location, and are regularly updated to keep up with changes in the cost of living. Increments based on disability, gender, ethnicity and other proxies for high vulnerability may warrant consideration in contexts of systemic discrimination or disadvantage (see ILO, UNICEF and Learning for Well-Being Institute 2024).

Adequacy does not refer only to the value at which child and family benefits are set. It also refers to the adequacy of other benefits which can also positively impact child well-being (figure 4.6). Where there is a comprehensive range of adequate life-cycle protection for other groups, such as those of working age and pensioners in households with children, this also protects child well-being.

4.1.5 Filling the financial gap in social protection for children

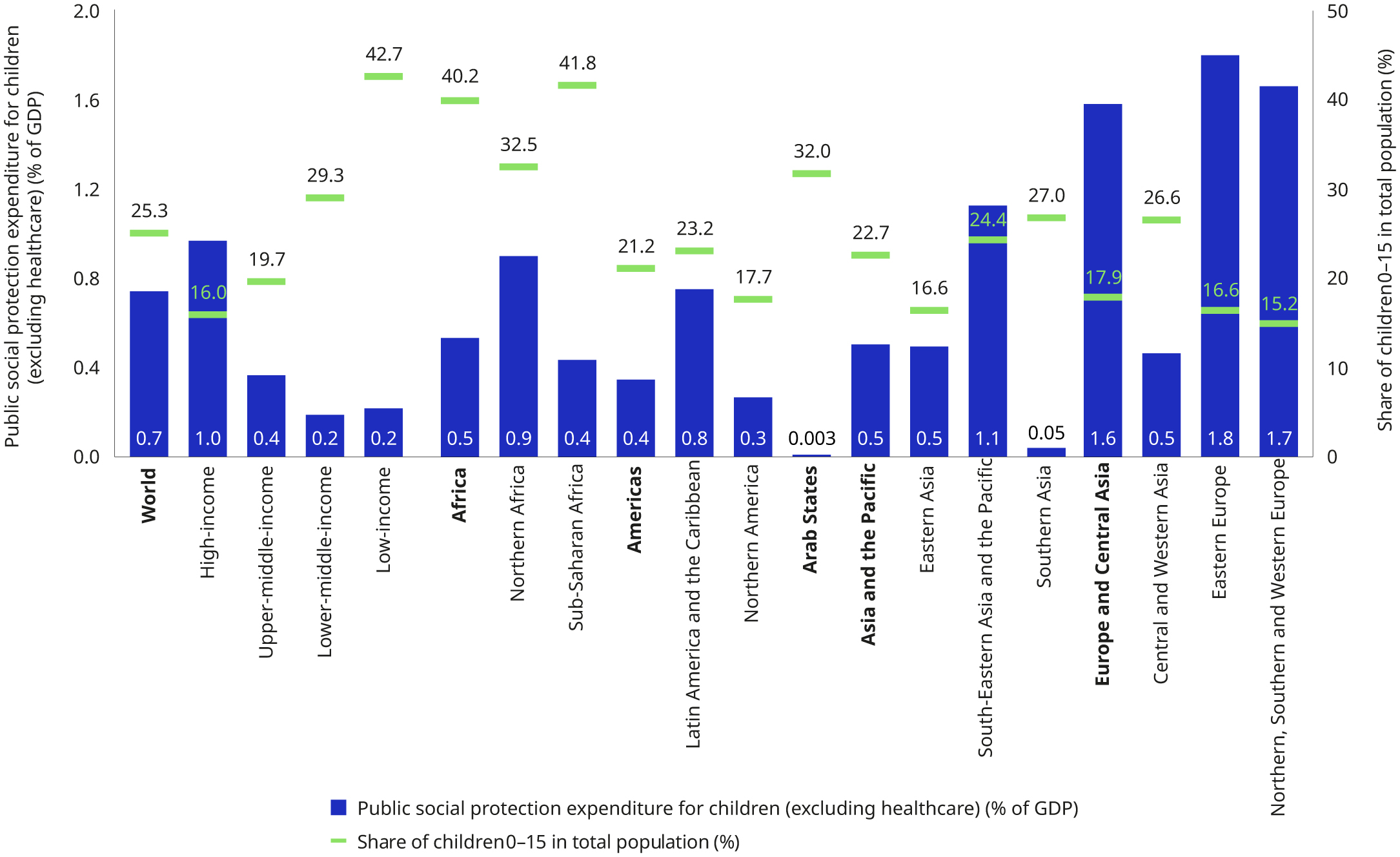

Figure 4.7 Public social protection expenditure (excluding health) on children (percentage of GDP) and share of children aged 0 to 15 in total population (percentage), by region, subregion and income level, 2023 or latest available year

Notes: See Annex 2 for a methodological explanation. Global and regional aggregates for expenditure are weighted by GDP.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ADB, GSW, IMF; OECD; UNECLAC; UNWPP, national sources.

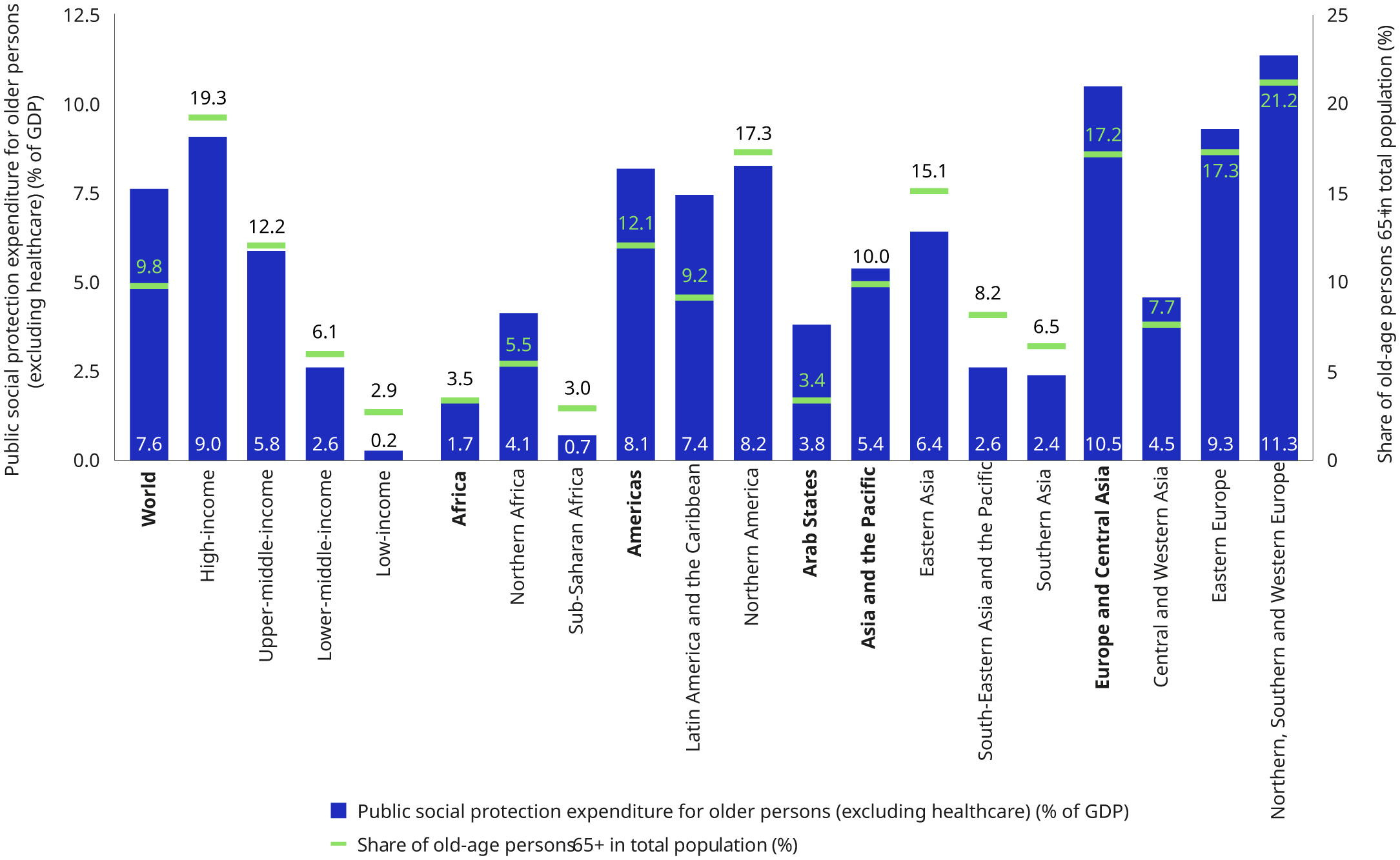

Ensuring adequate social protection requires sufficient resources to be allocated for children and families. Yet, average social protection expenditure for children (excluding health expenditure) across the world currently amounts to only 0.7 per cent of GDP (figure 4.7), with great variation across countries. While countries in Europe and Central Asia spend more than 1 per cent of GDP, expenditure ratios remain well below that threshold in other parts of the world. Regional estimates for Africa, Asia and the Pacific, and the Americas show expenditure levels of 0.5 per cent of GDP or below. An average expenditure level of only 0.2 per cent and 0.4 per cent of GDP in low-and upper-middle-income countries, respectively, lags behind the expenditure of 1.0 per cent of GDP in high-income countries.

Climate action to ensure social justice for children requires more equitable intergenerational expenditure and the filling of the financing gap. Currently, too little is spent on social protection. And too little of this expenditure is devoted to children, especially in the early years (ILO and UNICEF 2023). Globally, out of the total social protection expenditure, only 3.8 per cent is spent on children, contrasting with 33.0 per cent on healthcare, 38.7 per cent on pensions, and 24.6 per cent on working-age benefits. While children are indirectly protected by the benefits received by adult household members, this expenditure distribution is still hugely disproportionate and insufficiently focused on children.

The big challenge for closing protection coverage gaps for children lies in filling the social protection finance gap. To guarantee at least a basic level of social security for all children, lower-middle-income countries would need to invest an additional US$88.8 billion and upper-middle-income countries a further US$98.1 billion per year – equivalent to 1 and 0.3 per cent of GDP, respectively. Low-income countries would need to invest an additional US$59.6 billion, equivalent to 10.1 per cent of their GDP (Cattaneo et al. 2024). Options for expanding fiscal space are discussed in section 3.4.

There is also an opportunity to fill the financing gap and explore how climate financing can be leveraged for social protection. Given that children bear the brunt of the climate crises, despite contributing the least, and recognizing the role that social protection can play in climate action, climate financing could be considered to help fill the financing gap and contribute to closing coverage gaps. While several sources of climate finance can be considered – international public climate finance, international private investment, national and international carbon markets or domestic finance – international climate finance should not eat into the finance available for addressing development and humanitarian needs. Analysis indicates that, since 2018, more than half of the climate finance mobilized by developed countries was not additional to existing development assistance (Mitchell, Ritchie and Tahmasebi 2021).

4.1.6 Priorities, and recommendations

To respond to children’s ordinary life course needs, the climate crisis and a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies, social protection will be more crucial than ever. This requires:

-

Accelerating progress towards universal coverage and progressively covering all children . Almost all countries can improve their child benefit provision and there are different ways to achieve universal coverage. Countries can progressively realize their child benefit, introduce an age-limited benefit (for example, 0–2 years) and build gradually towards a more inclusive child benefit – ideally, a full universal child benefit for children between 0 and 18 years, and beyond. The recently launched Child Benefits Tracker4 provides an online platform to monitor children’s access to benefits and advocate for closing protection gaps.

-

Guaranteeing adequate benefit levels. For coverage to be transformative, it must deliver benefits set at values high enough to generate meaningful change in children’s lives and well-being. Providing increments for critical life course stages, such as the first two years of life, would be prudent.

-

Providing a comprehensive range of benefits . While social protection instruments directed at families with children are critical for ensuring children’s well-being, the evidence also points to the clear role of other social protection instruments across the life cycle. The combined power of life cycle protection leads to a stronger reduction of the drivers of diminished well-being through a system-wide approach.

-

Building social protection systems that are rights-based, gender-responsive and inclusive . Ensuring the well-being of children and addressing the conditions that adversely affect them require robust social protection systems and schemes. These need to be (a) anchored in law, rights-based and inclusive in all dimensions – including, but not limited to, gender, disability, migratory status, race and ethnicity – and (b) well coordinated with social services, care and family-friendly policies, and decent work opportunities for parents and caregivers.

-

Ensuring that social protection systems are linked with broader care and support services and decent work policies . Adequate social protection across the life cycle – together with childcare and education, and decent work for parents and other caregivers – is critical for the well-being of children. This also means extending social protection to workers in the informal economy and protection for workers in all types of employment.

-

Enhancing shock responsiveness is crucial for protecting children in a world riven by climate breakdown and other crises . Having in place comprehensive systems can enable countries to respond quickly; if necessary, align a humanitarian response with the national system-strengthening agenda; and address ordinary life-cycle challenges. Significant effort is therefore also needed to ensure that social protection systems and schemes are prepared before crises strike, while also channelling a rapid and effective response to shocks, to avert or lessen adverse child well-being impacts.

-

Ensuring sustainable and equitable financing for social protection systems. Mobilizing additional investment for social protection is key – tapping into loss and damage finance may be an option. It would compensate children for the climate threat they face and the fossil fuel excess of previous generations. It would also enable them to invest in the formation of capabilities required by a greener economy. Investment now would represent an act of intergenerational solidarity, and restorative and redistributive social justice, and would protect the rights of children yet to come.

.4.2 Social protection for women and men of working age

Key messages

-

A just transition to environmentally sustainable economies and societies requires adequate social protection for persons of working age to reduce their vulnerability, and support them in coping with shocks and slow-onset events, and in achieving their labour market transitions.

-

Yet, in many countries, persons of working age still face significant coverage gaps when it comes to life-cycle risks, such as sickness, maternity, disability, work injury, unemployment or death of a breadwinner. A lack of income security increases people’s vulnerability and erodes their capacities to adapt to changing conditions, including climate risks.

-

Social protection coverage is an essential element of decent work, and indispensable for people who are not able to work temporarily or permanently. Indeed, social protection coverage protects and promotes their capabilities, prevents poverty, enables them to navigate change and contributes to an inclusive recovery from crises.

-

Globally, 4.8 per cent of GDP is allocated to non-health public social protection expenditure for people of working age. While high-income countries allocate 6.3 per cent of their GDP to income security for people of working age, low-income countries can allocate only 0.4 per cent, leading to significant social protection gaps for their workers. Regional variation in social protection expenditure is large, ranging from 1.4 per cent of GDP in the Arab States to 7.1 per cent in the Americas.

-

Many countries still lack collectively financed social security benefit schemes that ensure income security in the event of maternity, sickness, unemployment and employment injury. Where the only available mechanisms are based on employer liability or private arrangements, results are often suboptimal in terms of coverage, equity and sustainability. Introducing mechanisms that are collectively financed through social insurance and/or general taxation can provide for wider coverage and more reliable benefits.

-

Effective coordination between social protection policies and employment, labour market, wage and tax policies is of critical importance to ensure an inclusive and job-rich recovery from crises.

4.2.1 Introduction: Making income security a reality

The ongoing transformations of economies and societies, whether related to the climate crisis, technological innovations or demographic change, require adequate social protection during working age. Adequate social protection is a key tool to reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience to enable people, societies and economies to adapt to change.

While gainful employment is the main source of income for people of working age, social protection has an important enabling role. It enables people to engage in decent and productive employment, protects and promotes their capabilities, facilitates a healthy balance between work and family responsibilities, and ensures a dignified life. According to the latest ILO modelled estimates, 60.5 per cent of people aged 15 and above are economically active and earn their livelihoods through income-generating activities; 72.9 per cent of men and 48.2 per cent of women (ILO 2024k). Yet, many find themselves in precarious and insecure employment arrangements, including in the informal economy, with limited job and income security and in poor working conditions (ILO 2023w). Globally, more than 2 billion people are in informal employment,5 representing 57.8 per cent of the workforce – 55.2 per cent of women and 59.6 per cent of men (ILO 2023w). Moreover, 241 million people are in extreme working poverty, that is, they live in extreme poverty despite being in employment (ILO 2023w). Another significant share of the global population, most of whom are women, perform unpaid care and household work, often in addition to paid work (ILO 2024a). All these persons of working age need social protection, whether in paid employment or not, whether working as employees or as self-employed, whether looking for a job, being temporarily or permanently incapable of working, or in education (ILO 2021m).

By partially or fully replacing lost incomes and providing income support to those affected, social protection systems have proven to be key in protecting and promoting human capabilities, smoothing incomes over people’s lives and stabilizing aggregate demand (ILO 2021o; 2020h; 2020k; 2020e). This includes income security6 in the event of maternity, sickness, work injury, disability, unemployment or death of the breadwinner (ILO 2021q; UN 2020), and helps people to find and sustain decent and productive employment. Social protection also facilitates effective access to healthcare and other services. Furthermore, it contributes to healthier lives by enhancing the social determinants of health (WHO, forthcoming, see also section 4.4) and to decent work in the care economy (ILO 2024a). Social protection systems are essential for protecting and promoting human capabilities, smoothing incomes over people’s lives and stabilizing aggregate demand (ILO 2021o; 2020h; 2020k; 2020e).

While some countries have heeded the lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic and other crises and invested in reinforcing their social protection systems, much more needs to be done to ensure that people of working age can enjoy the full protection that they need to:

-

engage in decent and productive employment,

-

benefit from income security also in times when they are not able to work temporarily or permanently, and

-

balance their work and family responsibilities.

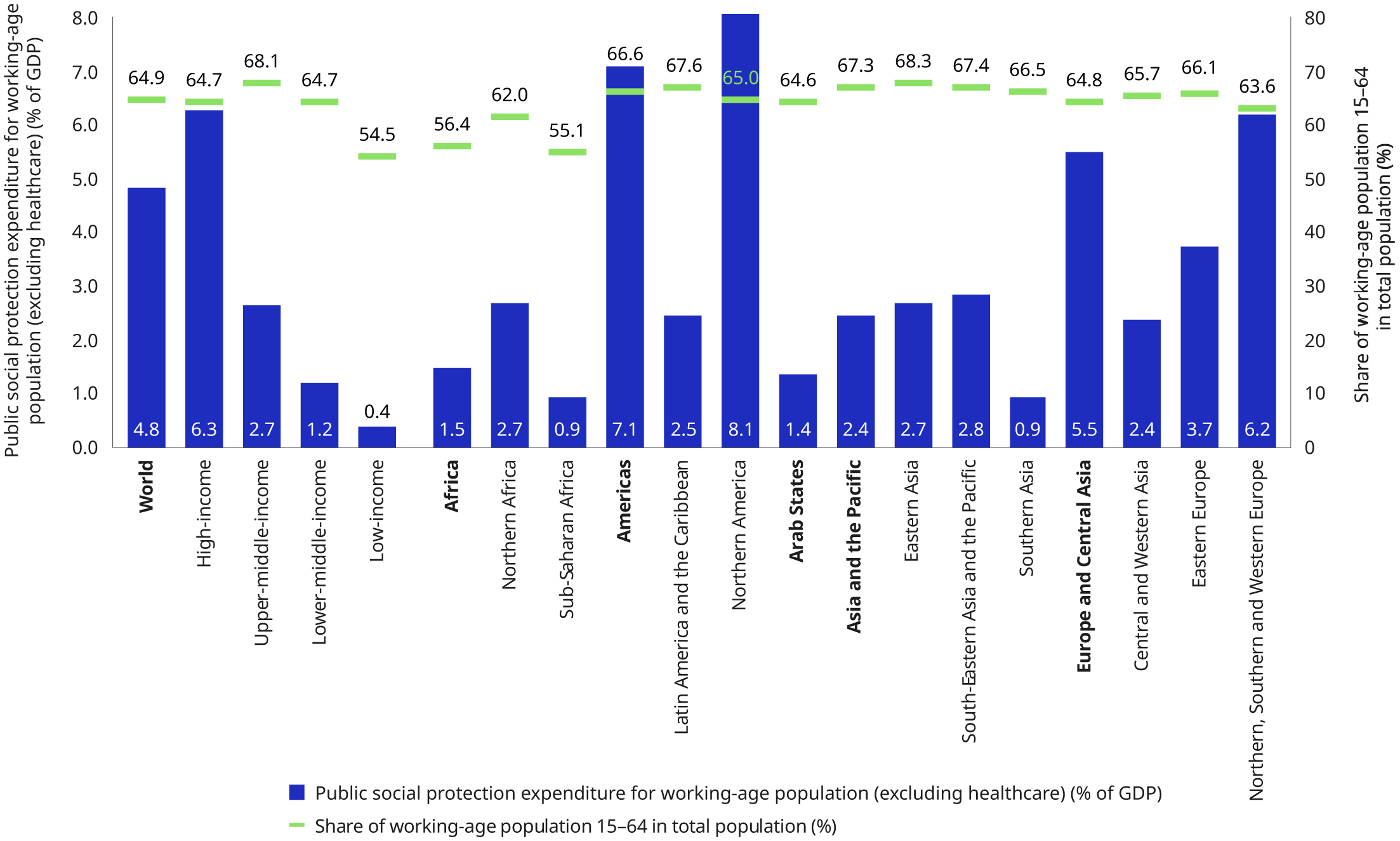

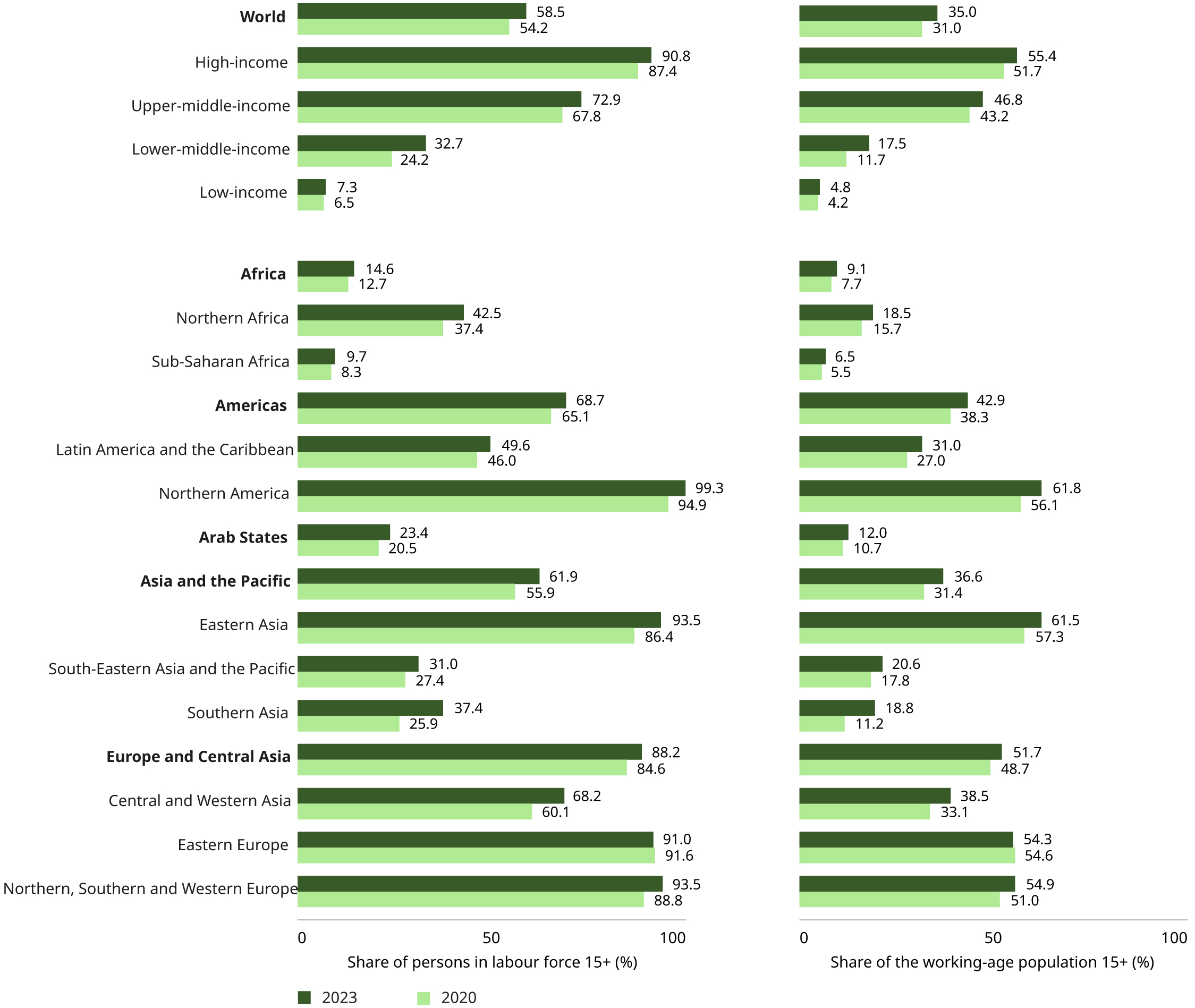

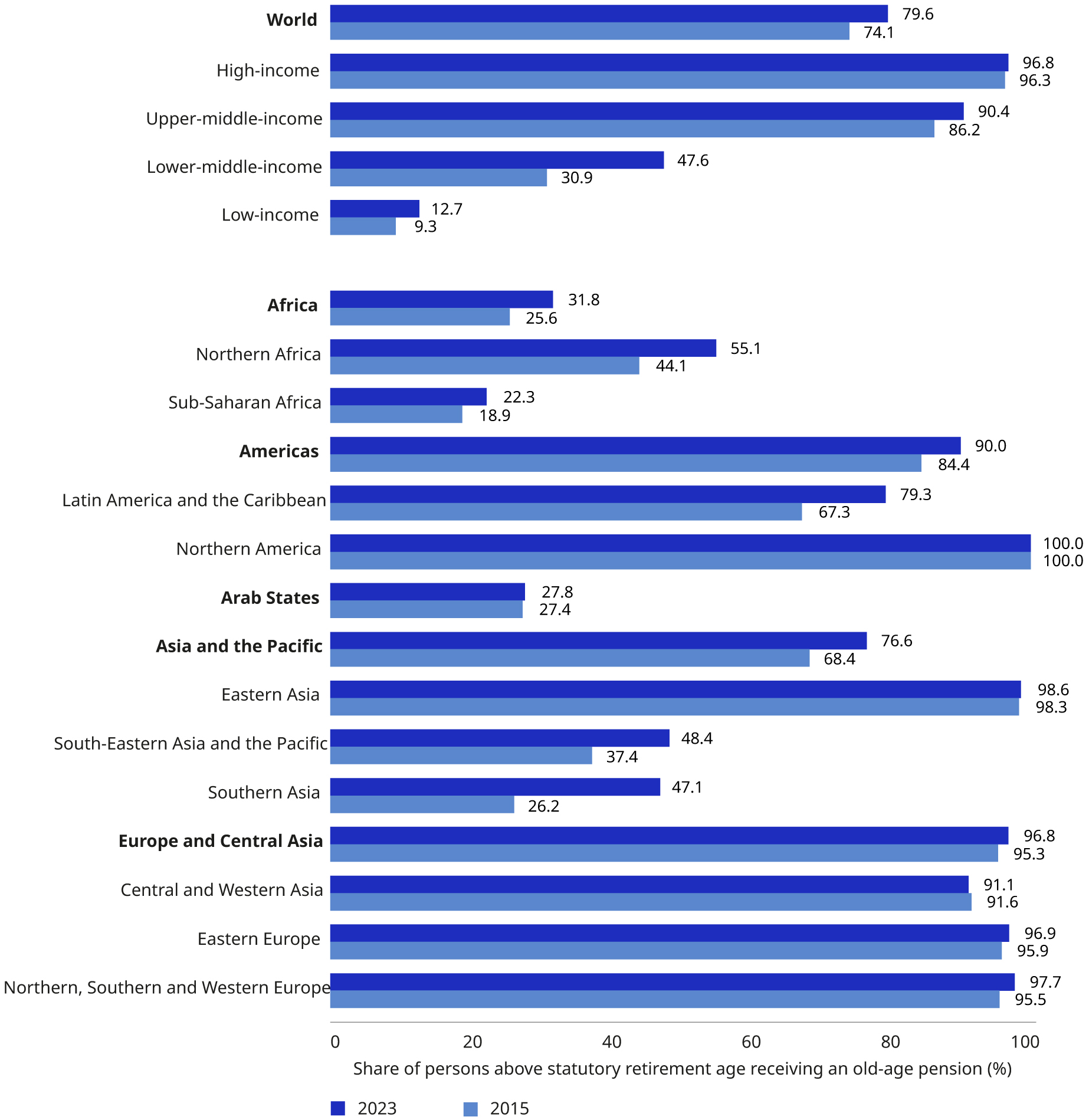

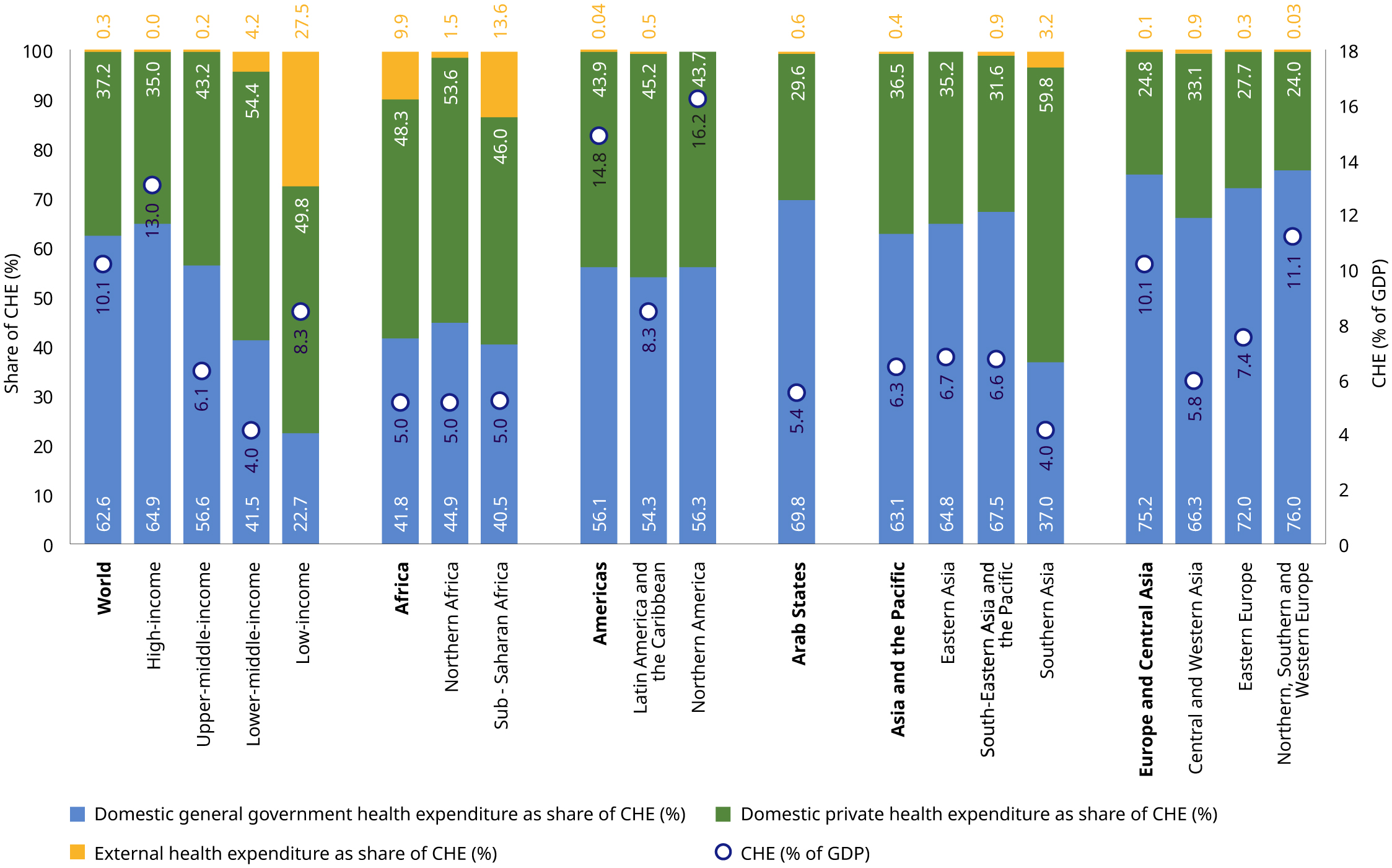

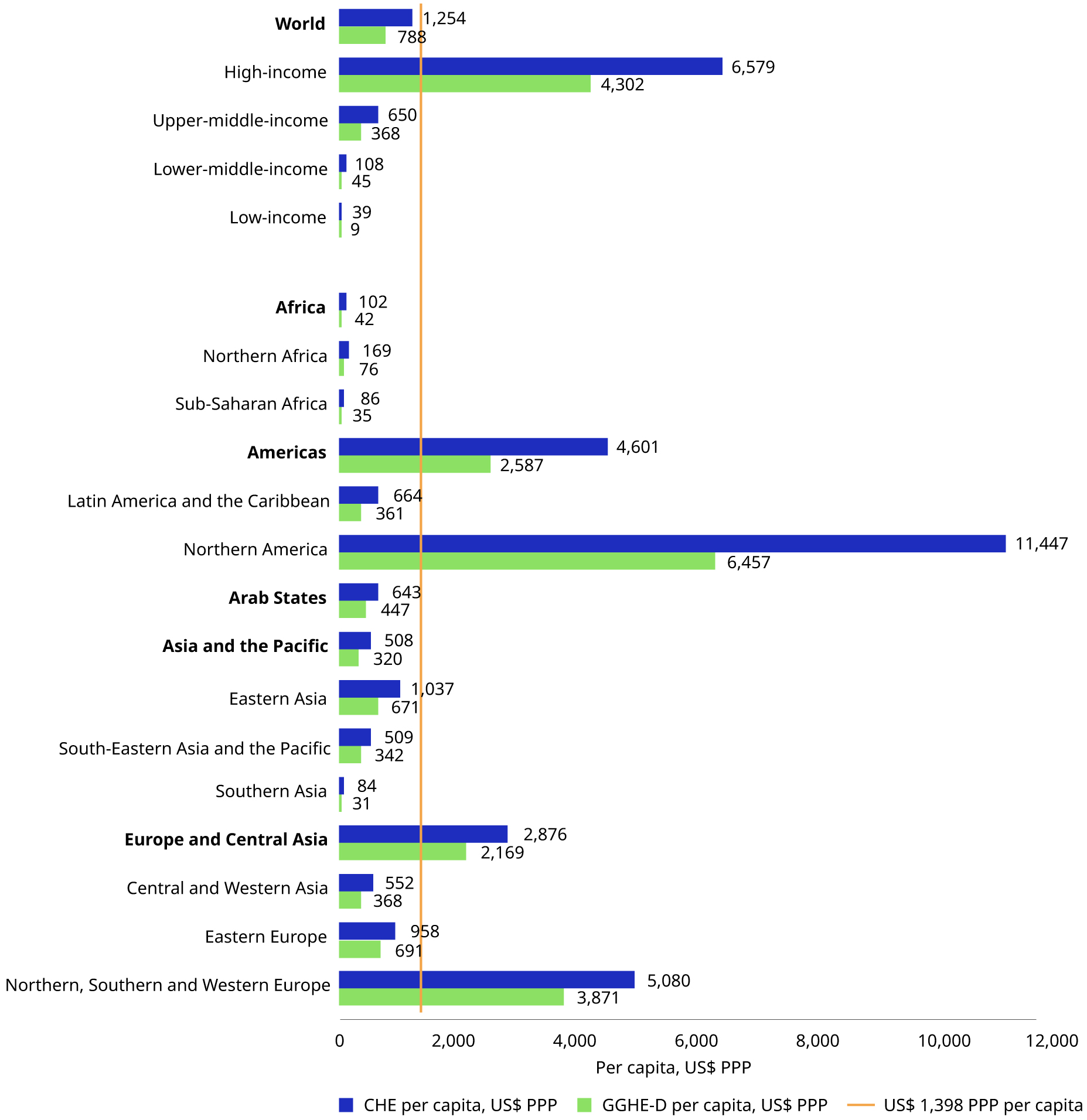

Figure 4.8 Public social protection expenditure (excluding health) on working-age population (percentage of GDP) and share of population aged between 15 and 64 in total population (percentage), by region, subregion and income level, 2023 or latest available year

Note: See Annex 2 for a methodological explanation. Public social protection expenditure for working-age population (excluding healthcare) global and regional aggregates are weighted by GDP.

Sources: ILO estimates, World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ADB, GSW, IMF; OECD; UNECLAC; UNWPP, national sources.

Large coverage gaps are associated with significant underinvestment in social protection for people of working age, including maternity benefits, unemployment benefits, employment injury benefits, disability benefits, survivor benefits and general social assistance, but excluding healthcare (covered in section 4.4). Globally, countries allocate on average 4.8 per cent of their GDP to non-health social expenditure for persons of working age (see figure 4.8), ranging from 6.3 per cent of GDP in high-income countries, to only 0.4 per cent in low-income countries. Regional variations are also significant, ranging from 1.4 per cent of GDP in the Arab States, 1.5 per cent in Africa and 2.4 per cent in Asia and the Pacific, to 5.5 per cent in Europe and Central Asia, and 7.1 per cent in the Americas. The comparison with the share of the working-age population in the total population demonstrates that demographic factors can only explain part of the regional variation and the relative underdevelopment of social protection programmes for persons of working age.

While social protection plays an essential role in ensuring income security, it is clear that income security cannot be achieved by social protection systems alone. To promote decent work, social protection policies need to be well coordinated with policies in other areas, particularly labour market and employment policies (including active labour market policies), employment protection, occupational safety and health, wages (including minimum wages) and collective bargaining. Social protection policies would also benefit from being aligned with policies that support the formalization of enterprises and employment, policies to support workers with family and care responsibilities and policies to promote gender equality in employment.7 Such an integrated approach is essential for achieving the SDGs and ensuring decent work and social justice for all.

The remainder of this section of Chapter 4 is divided into five subsections, dealing in turn with the areas of social security that are most relevant to people of working age, namely:

-

maternity protection, paternity and parental leave benefits (section 4.2.2);

-

sickness benefits (section 4.2.3);

-

employment injury protection (section 4.2.4);

-

disability benefits (section 4.2.5); and

-

unemployment protection (section 4.2.6).

Each of these subsections discuss both contributory and non-contributory schemes, which together ensure universal coverage with adequate benefits, based on sustainable and equitable financing mechanisms. Although the primary focus is on cash benefits, the discussion will also take into account that benefits in kind – in particular healthcare, care and other social services8 (Martínez Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea 2015) – play a major role in ensuring income security for people of working age. Access to healthcare is discussed in more detail in section 4.4. Together, these schemes contribute to building national social protection systems, including floors.

4.2.2 Maternity protection, paternity and parental leave benefits

Key messages

-

Exposure to climate change hazards, such as extreme heat, weather events and air pollution, has consequences for maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, including gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, preterm birth, low birth weight and stillbirth but also exposure to vector-borne diseases. These impacts have implications for maternity protection, leading to increased demands on health and maternity care systems. Yet, inequalities in access to reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health persist, with significant differences within and between countries, depending on income, education level and place of residence.

-

Maternity benefits and maternity care provision are crucial to ensure that women in their final stages of pregnancy and after childbirth are not forced to keep working and do not expose themselves and their children to significant health risks. Such benefits directly support income security, therefore addressing some of the key social determinants of poor maternal and child health and early childhood development.

-

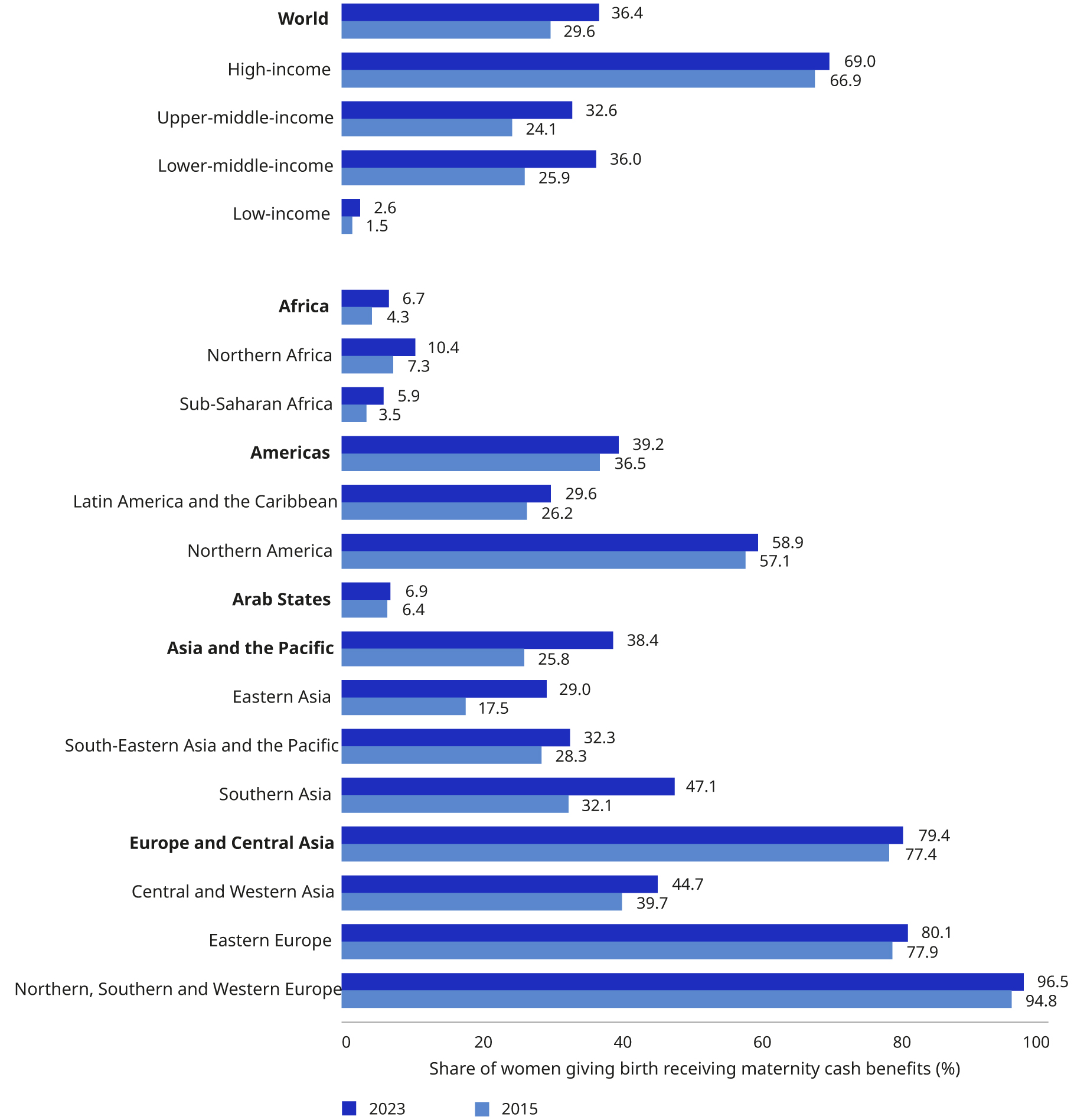

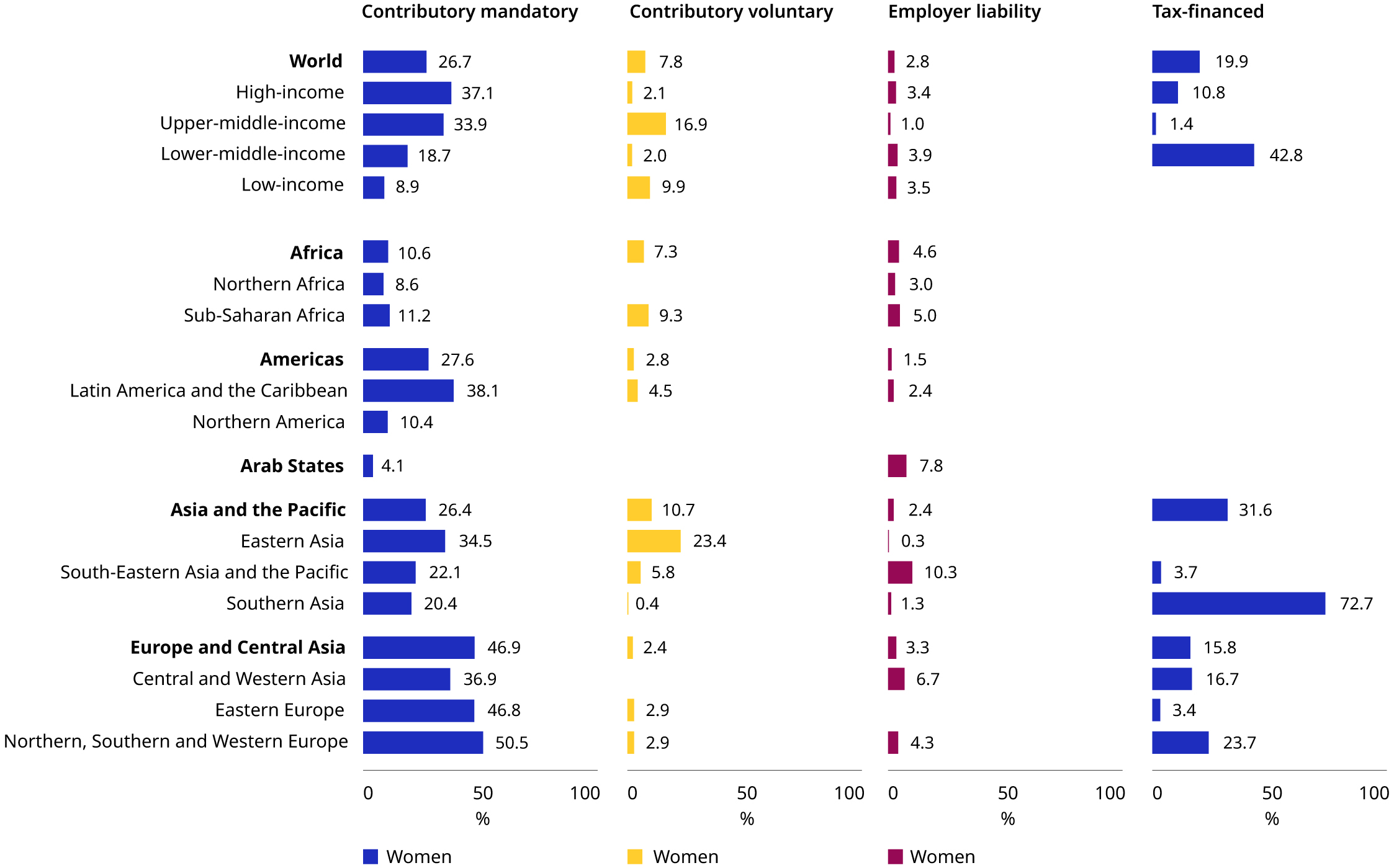

Only slightly more than a third (36.4 per cent) of women with newborns worldwide received a maternity cash benefit in 2023, a slight increase compared to 29.6 per cent in 2015. Coverage varies significantly across regions and income levels: coverage of childbearing women is close to universal in most of Europe, compared to a mere 2.6 per cent in low-income countries and 5.9 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa. Similarly, free maternity care is not universally available.

-

Maternity protection includes income security (through cash benefits), leave policies and effective access to free quality maternal and newborn healthcare services. In addition, employment and labour market interventions – such as employment protection and non-discrimination, childcare solutions after return to work, adequate occupational health and safety measures and breastfeeding facilities at the workplace – are important to give adequate protection to pregnant women and new mothers.

-

Adequate provision for paid paternity leave is an important corollary to maternity protection policies and contributes to a more equal sharing of family responsibilities and other unpaid care work. In 2021, 115 out of 185 countries surveyed by the ILO offered a right to paid paternity leave, with an average duration of nine days.

The importance of increased maternity protection in a changing climate

Maternity protection is crucial for preventing and alleviating poverty and vulnerability, enhancing the health, nutrition and overall well-being of mothers and newborns, fostering gender equality and promoting a dignified life for all from the very start. It encompasses provisions such as income support, access to maternal healthcare, paid maternity leave, time to breastfeed, safeguards against discrimination in employment, parental leave, right to return to work and childcare options upon returning to work. While these are mainly labour protection measures, this section focuses on maternity protection measures pertaining to social protection, that is, maternity cash benefits and free maternity care. Social protection systems are essential for minimizing the adverse impacts of the climate crisis on pregnant and childbearing women and their children.

As a fundamental element of maternity protection and social health protection, good maternal healthcare without hardship provides for effective access to adequate healthcare and services – including reproductive health services – during pregnancy and childbirth and beyond, lifting financial barriers to ensure the health of both mothers and children. As with social health protection in general (see section 4.4), a lack of coverage puts the health of women and children at risk and exposes families to significantly increased risk of poverty, and can act as an incentive to forgo care.

Climate change affects pregnant women directly and indirectly, in the long and short term, and can be caused by sudden- as well as slow-onset events. The threat of the climate crisis to livelihoods, particularly among vulnerable populations (see section 2.1), impacts the social determinants of health and increases the health risks of pregnant women related to income insecurity, poor nutrition, water, hygiene, sanitation and access to health services. Forced migration and displacement due to lost livelihoods or environmental shocks and disasters adversely impact the health of all members of affected communities (Chapter 2), but can be most life threatening for pregnant women, new mothers and newborns who are in critical need of adequate nutrition, access to healthcare, and sufficient rest. A large body of studies shows that the exposure to climate change hazards such as extreme heat, adverse weather events and air pollution have consequences for maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality (including gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, preterm birth, low birth weight and stillbirth) but also exposure to vector-borne diseases. Both direct and indirect exposure to climate hazards can also affect mental health, increasing risk for stress, anxiety and depression – known risk factors for adverse perinatal outcomes (WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA 2023a). Women in the informal economy are particularly vulnerable to the risks of income insecurity and ill health because of discrimination, unsafe and insecure working conditions, lack of employment protection, often low and volatile incomes, limited freedom of association, lack of representation in collective bargaining processes and lack of access to social insurance (ILO 2016a).

In light of these increased risks, providing adequate maternity protection is paramount. Yet, evidence points to significant gaps in coverage, adequacy, comprehensiveness and financing for benefits and services to which pregnant women and their newborns should have access.

A comprehensive approach to maternity protection

According to international labour standards (see box 4.4), maternity protection includes not only income security and access to free maternal healthcare, but also the right to interrupt work activities, to rest and to recover around childbirth. It ensures the protection of women’s right to work and rights at work during maternity and beyond, through measures that prevent risks, protect pregnant women from unhealthy and unsafe working conditions and environments, safeguard their employment, protect them against discrimination and dismissal, and allow them to return to their jobs after maternity leave under conditions that take into account their specific circumstances, including the need for breastfeeding (Addati, Cattaneo and Pozzan 2022). From the perspective of equality of opportunity for and treatment of women and men, maternity protection takes into account the particular circumstances and needs of women, enabling them to enjoy their economic rights while raising their families (ILO 2014b; 2018e). For example, maternity protection starts even before conception, with the ability of women to freely determine the number of children they want to have, and the intervals at which they have them, through access to affordable and good-quality sexual and reproductive rights and services (Folbre 2021). In the absence of such services, women carry the social, economic and health consequences of unwanted pregnancies or unsafe abortions, which are especially severe in the case of adolescent mothers.

Maternity protection can also counteract the “motherhood penalty”, that is, the disadvantages faced by mothers of young children compared to fathers or to women without children. Mothers are less likely to be employed, receive lower wages and are less likely to work in managerial or leadership positions than women without children, fathers and men without children.

Box 4.4 International standards relevant to maternity protection

|

Women’s right to maternity protection is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), which sets out the right to social security and special care and assistance for motherhood and childhood. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966) establishes the right of mothers to special protection during a reasonable period before and after childbirth, including prenatal and postnatal healthcare and paid leave or leave with adequate social security benefits. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979) recommends that special measures be taken to ensure maternity protection, proclaimed as an essential right permeating all areas of the Convention. Since the adoption by the ILO of the Maternity Protection Convention, 1919 (No. 3), in the very year of its foundation, a number of more progressive instruments have been adopted, in line with the steady increase in women’s participation in the labour market in most countries worldwide. The Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102), Part VIII, sets minimum standards as to the population coverage of maternity protection schemes, including cash benefits during maternity leave, to address the temporary suspension of earnings (see Annex 3, table A3.7). The Convention also defines the medical care that must be provided free of charge at all stages of maternity, to maintain, restore or improve women’s health and their ability to work. Further, it provides that free maternal healthcare must be available to women and the spouses of men covered by maternity protection schemes. The Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183), and its accompanying Recommendation (No. 191), provide detailed guidance for national policymaking and action aiming to ensure that women:

In order to protect women’s rights in the labour market and ensure that maternity does not constitute a source of discrimination by employers, ILO maternity protection standards specifically require that cash benefits be provided through schemes based on solidarity and risk pooling, such as compulsory social insurance or public funds, while strictly limiting the potential liability of employers for the direct cost of benefits. Recommendation No. 202 calls for access to essential healthcare, including maternity care and basic income security, for people of working age who are unable to earn sufficient income owing to (among other factors) maternity. Cash benefits should be sufficient to allow women a life in dignity and without poverty. Maternal healthcare services should meet criteria of availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality (UN 2000a); they should be free and not create hardship or increase the risk of poverty for people in need of healthcare. Maternity benefits should be granted to all residents of a country. Reinforcing the objective of achieving universal protection, the Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy Recommendation, 2015 (No. 204), calls for the extension of maternity protection to all workers in the informal economy. |

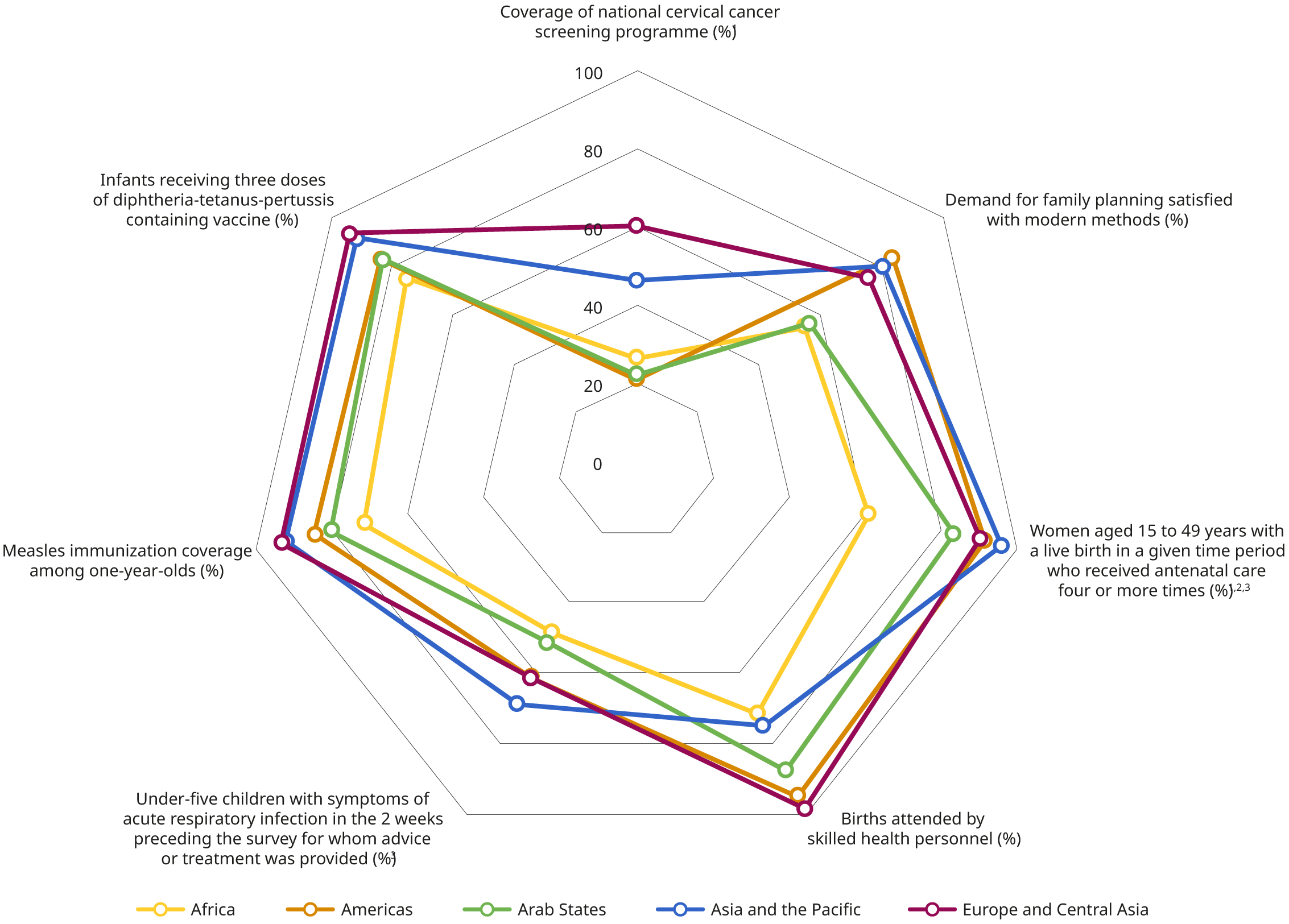

Access to reproductive, maternal, newborn and child healthcare

Effective access to appropriate prenatal and postnatal healthcare services without hardship for pregnant women and mothers with newborns is an essential component of maternity protection and social health protection alike. Making such services free helps lift the financial barriers of access to healthcare that may be particularly pronounced for women. It is important in order to improve maternal and child health, reduce maternal and child mortality, reach universal health coverage and achieve gender equality (SDG targets 3.1, 3.2, 3.8 and 5.6). Access to healthcare in general (SDG target 3.8) is discussed in detail in section 4.4.

This is all the more important, as many women suffer from pregnancy or childbirth complications. While the global maternal mortality ratio declined by 34 per cent between 2000 and 2020, 287,000 women (223 deaths per 100,000 live births) globally died from a maternal cause in 2020, equivalent to almost 800 maternal deaths every day, approximately one every two minutes. As many as 95 per cent of all maternal deaths occurred in low-and lower-middle-income countries (WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA 2023b).

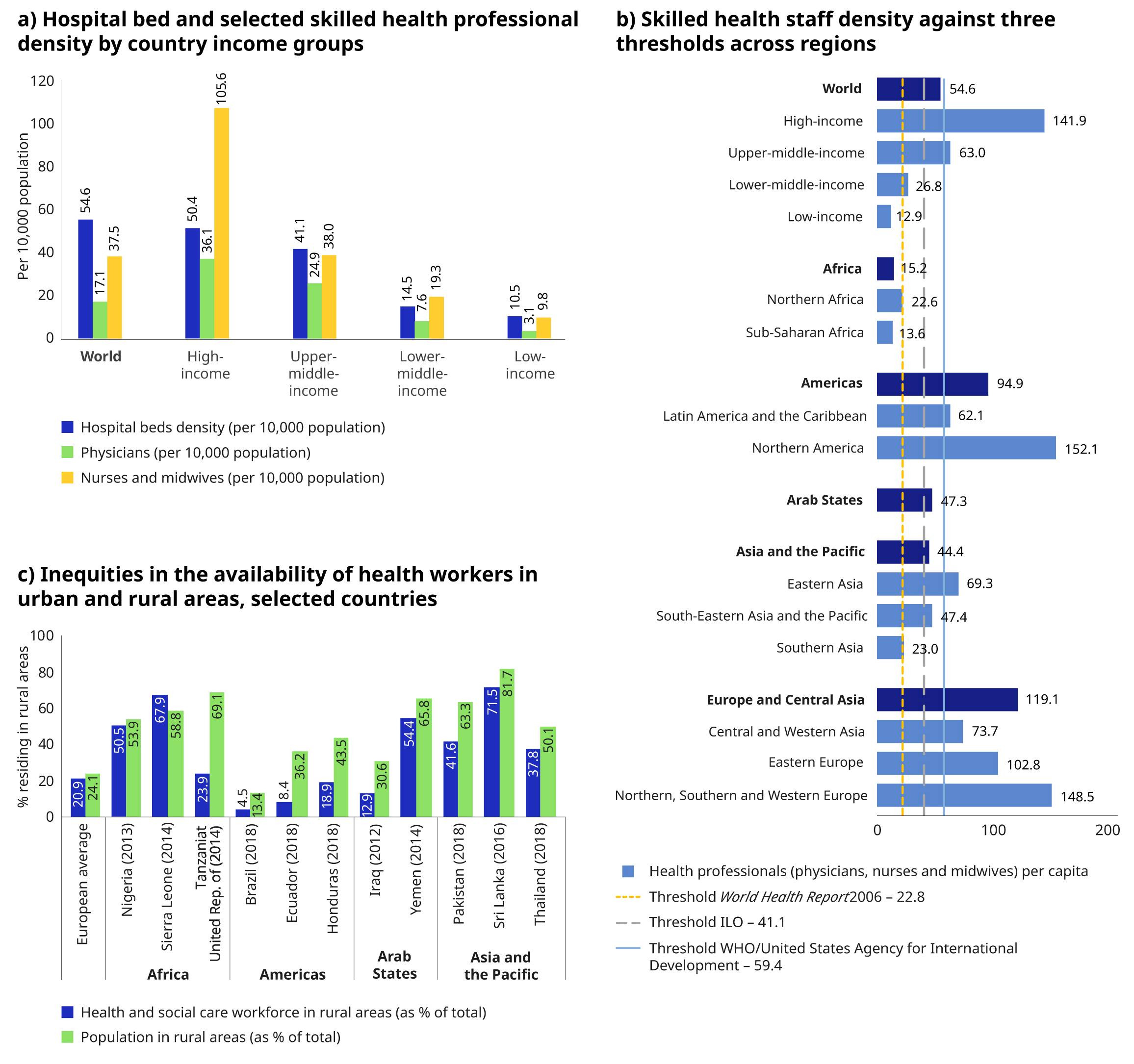

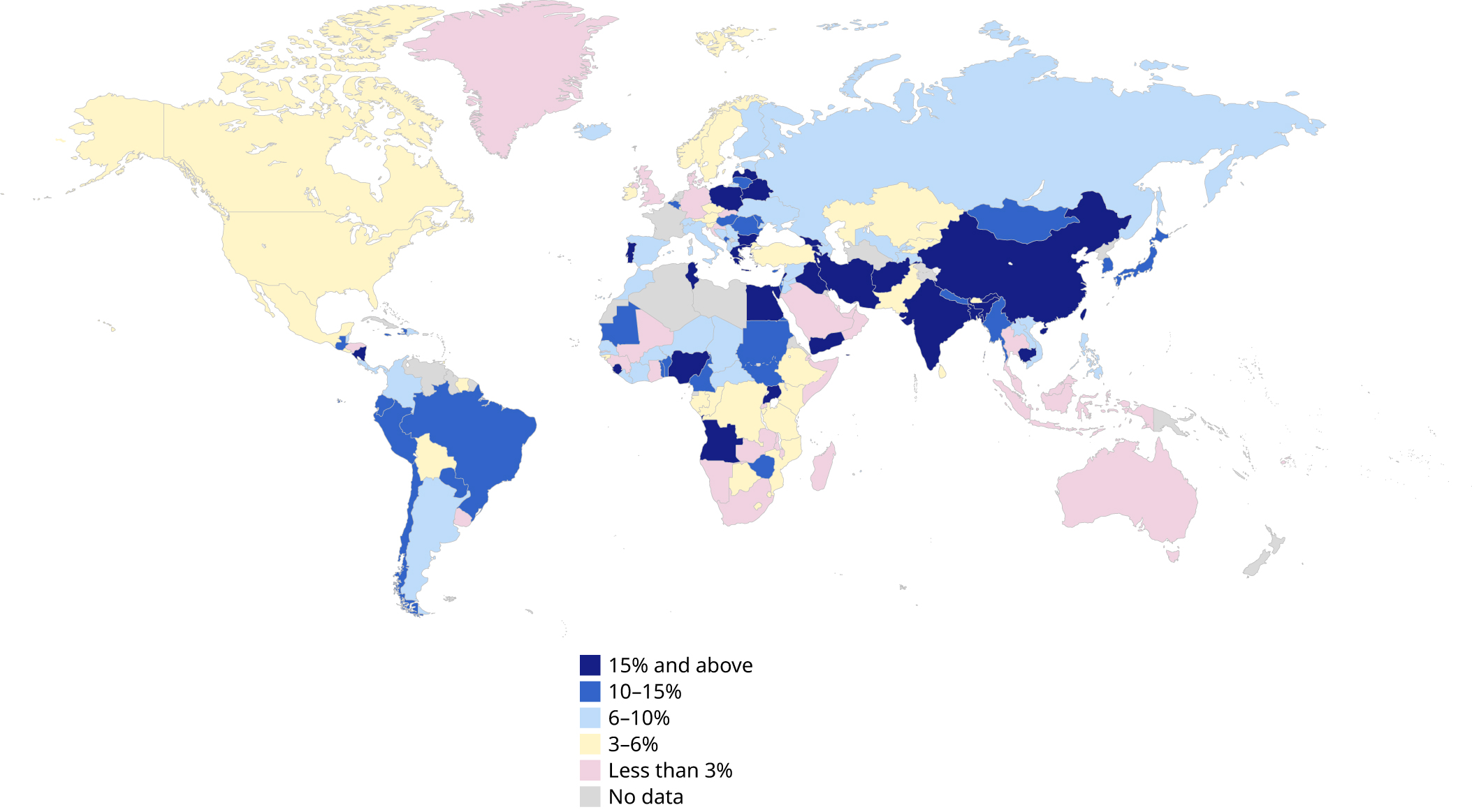

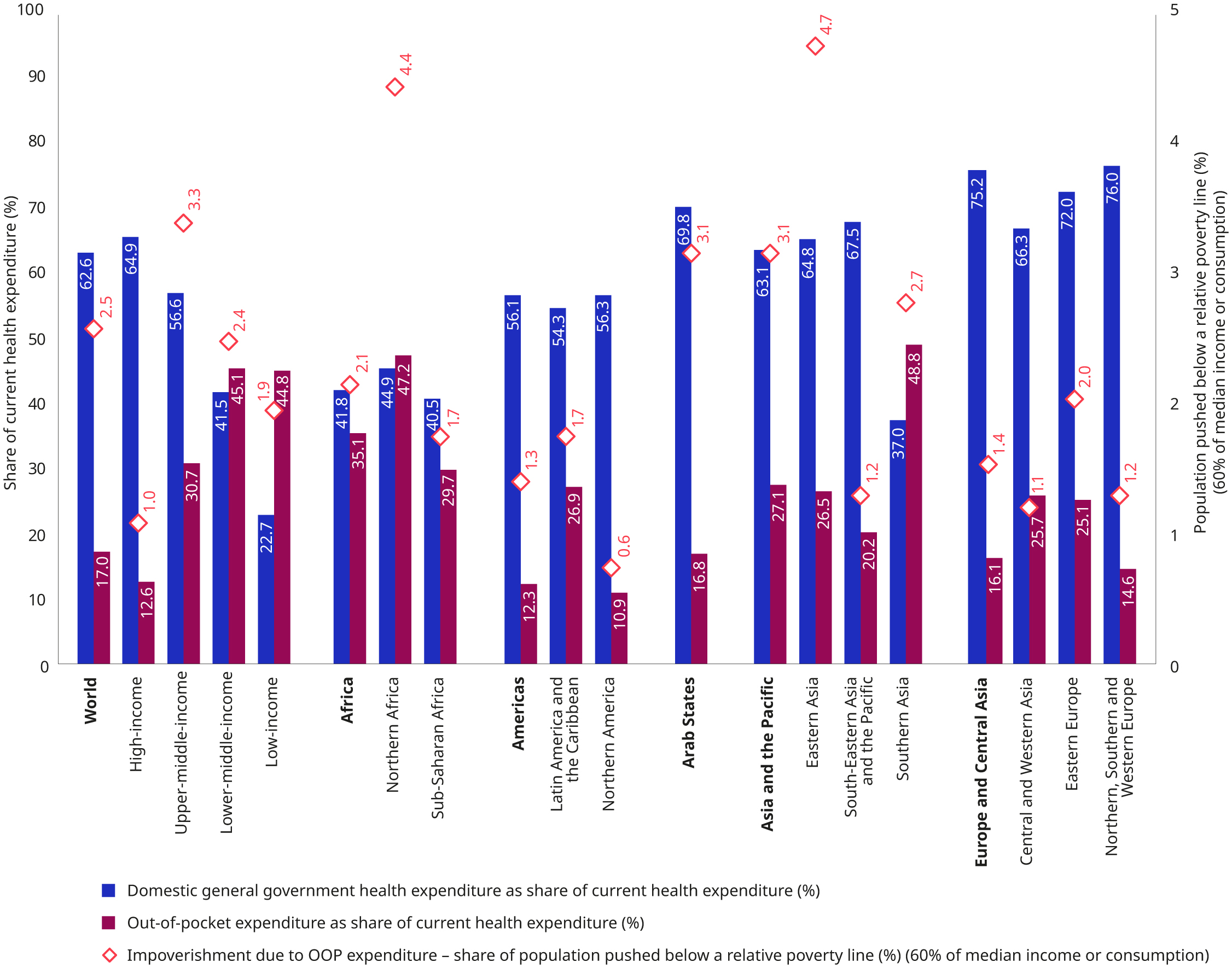

Apart from access to free adequate health services, many socio-economic factors determine the health outcomes of pregnant women. These conditions are further impacted by climate change as maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality are expected to increase with an increased frequency of extreme weather events (Segal and Giudice 2022; Dodzi Nyadanu et al. 2024). The health impact of the climate crisis on pregnant women will increase demands on the health system. Therefore, it is important that health staff are trained to raise awareness of climate-related health risks for pregnant women. The needs of pregnant women should be integrated into climate-sensitive health policy planning to guarantee adequate access to essential sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health services. This will also require additional financing to meet current unmet needs and future increases in demand. However, trend analysis of the subindices of SDG target 3.8.1 on reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health (encompassing family planning, prenatal care, diphtheria tetanus toxoid and pertussis immunization, and acute respiratory infection care seeking) shows very slow progress in the availability of such services over the last two decades (period 2000–21) (WHO and World Bank 2023). The average annual changes have been below 1 per cent since 2000 and no changes have been observed since 2015. Furthermore, large inequalities between countries persist, with much better access to services in high-income countries while low-and lower-middle-income countries lag behind.

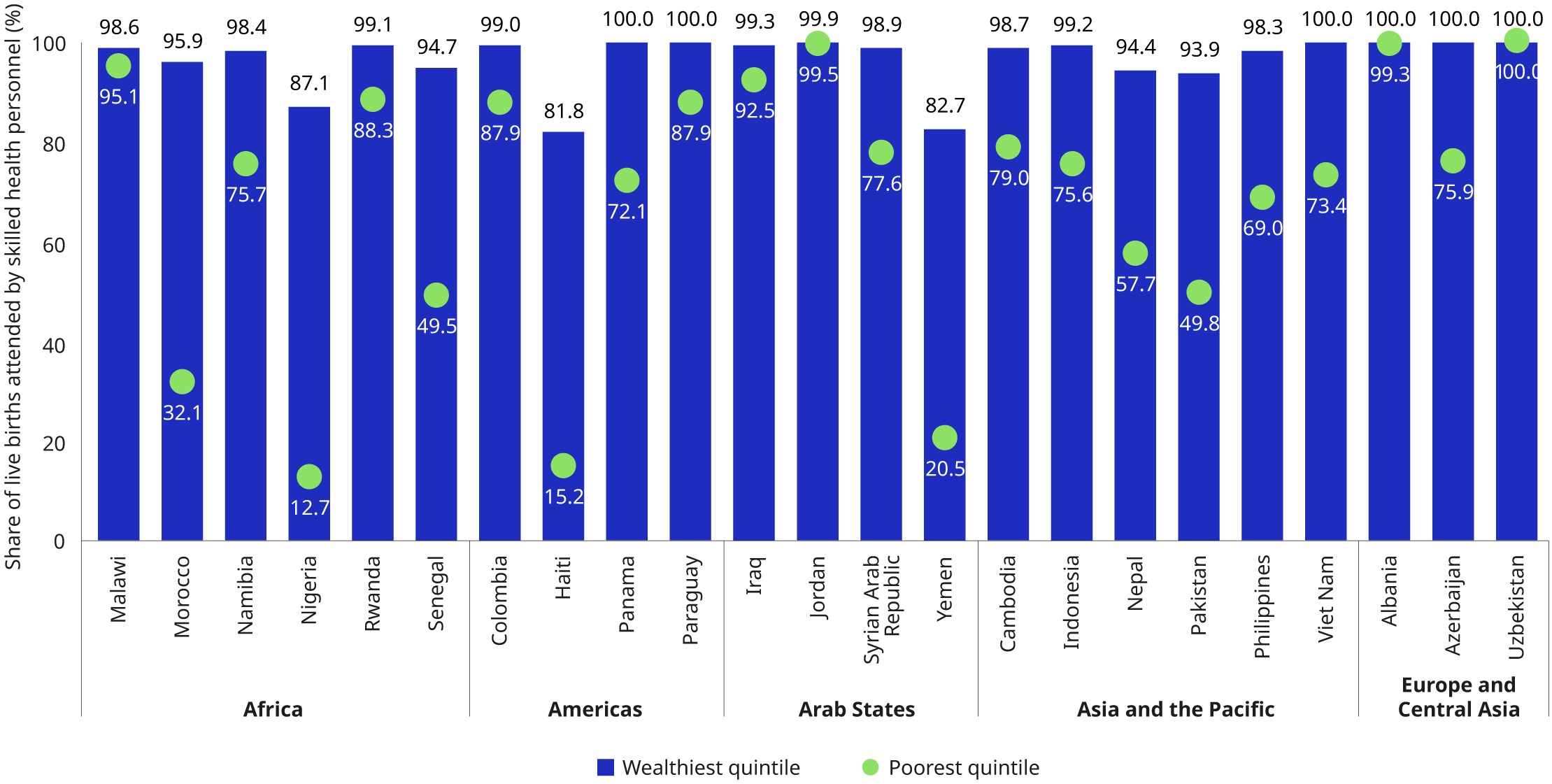

Similarly, inequalities within countries persist by economic status, education and place of residence (urban or rural). The analysis of a subset of 78–89 countries for which disaggregated data is available, shows that there is a striking social gradient in access to reproductive, maternal and child health services, with a difference of almost 15 percentage points between highest (median coverage of 73 per cent) and lowest quintiles (58 per cent) and an overall difference of 3–4 percentage points between each quintile. There are also inequalities between urban (70 per cent) and rural (63 per cent) populations and also between those without education (56 per cent) and secondary or higher education (71 per cent) (WHO and World Bank 2023). Patterns of inequality also prevail when considering intersectional discrimination. For example, women with disabilities are found to be regularly excluded from the provision of sexual and reproductive health services and face the additional risk of involuntary sterilization (UN 2019a). Particular efforts are therefore needed to ensure effective access for expecting women with disabilities, who face additional barriers in meeting their sexual and reproductive healthcare needs, including societal misperceptions and stereotypes around their sexuality, inaccessibility of services and/or information and fear of abuse.

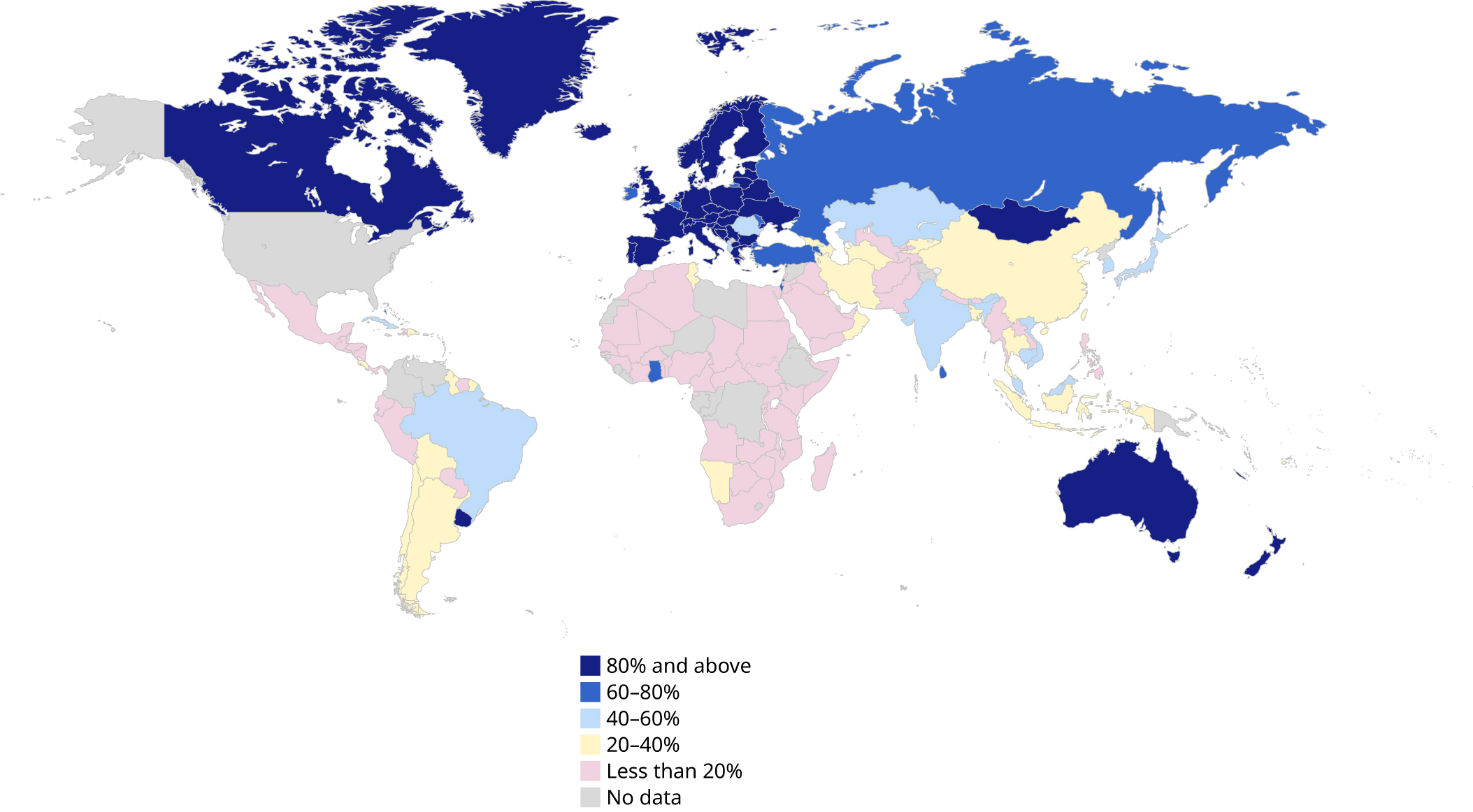

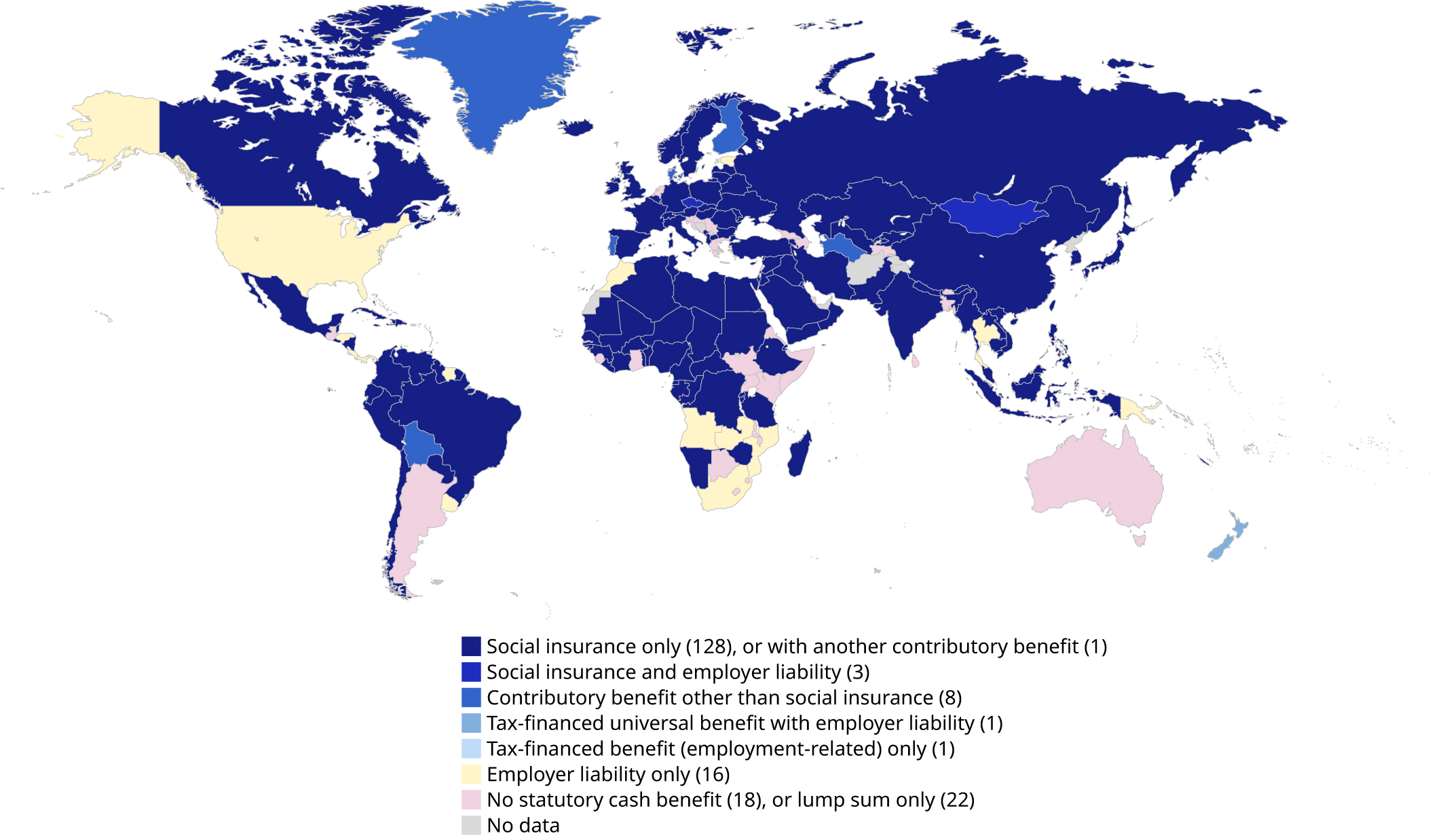

A diversity of schemes providing maternity benefits

Globally, 157 out of 217 countries and territories have periodic maternity cash benefits anchored in national legislation, of which 142 have social insurance and 11 have tax-financed employment-related schemes (figure 4.9); 119 have social insurance as the only mechanism and 7 in combination with means-tested benefits; and 16 combine social insurance with employer liability. Four countries and territories have universal tax-financed maternity benefits, one of them in combination with employer liability. A total of 49 countries still only have employer liability mechanisms, which present challenges in terms of access and adequacy of protection.

The Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183), recommends that countries introduce collectively financed maternity benefits (social insurance or tax-financed) rather than relying on employers’ liability provisions. This improves equality of treatment for men and women in the labour market because it shifts the burden of bearing the costs of maternity benefits from the individual employer to the collective, reducing discrimination against women of childbearing age in hiring and in employment, and the risk of non-payment of due compensation by the employer. Such reforms can also facilitate the coverage of women with low contributory capacities and interrupted employment histories, including those in part-time or temporary employment, and those in self-employment.

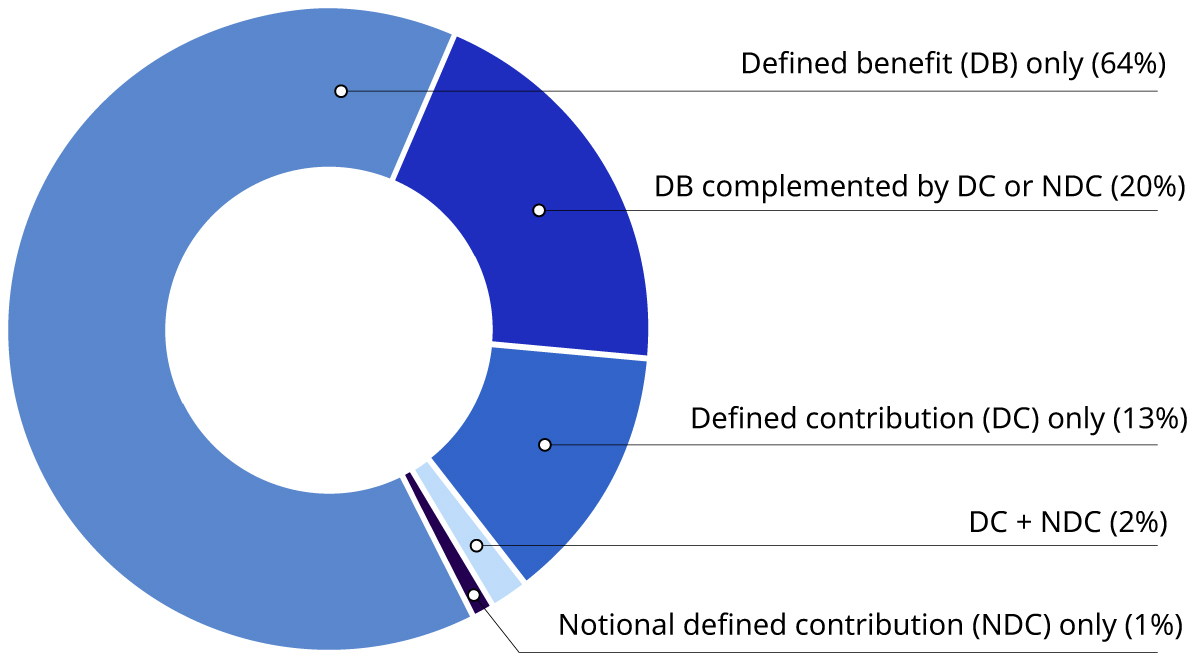

Figure 4.9 Maternity protection (cash benefits) anchored in law, by type of scheme, 2023 or latest available year

Disclaimer: Boundaries shown do not imply endorsement or acceptance by the ILO. See full ILO disclaimer.

Note: The number between parentheses refers to the count of countries or territories.

Sources: ILO modelled estimates; World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources.

Coverage of maternity benefits

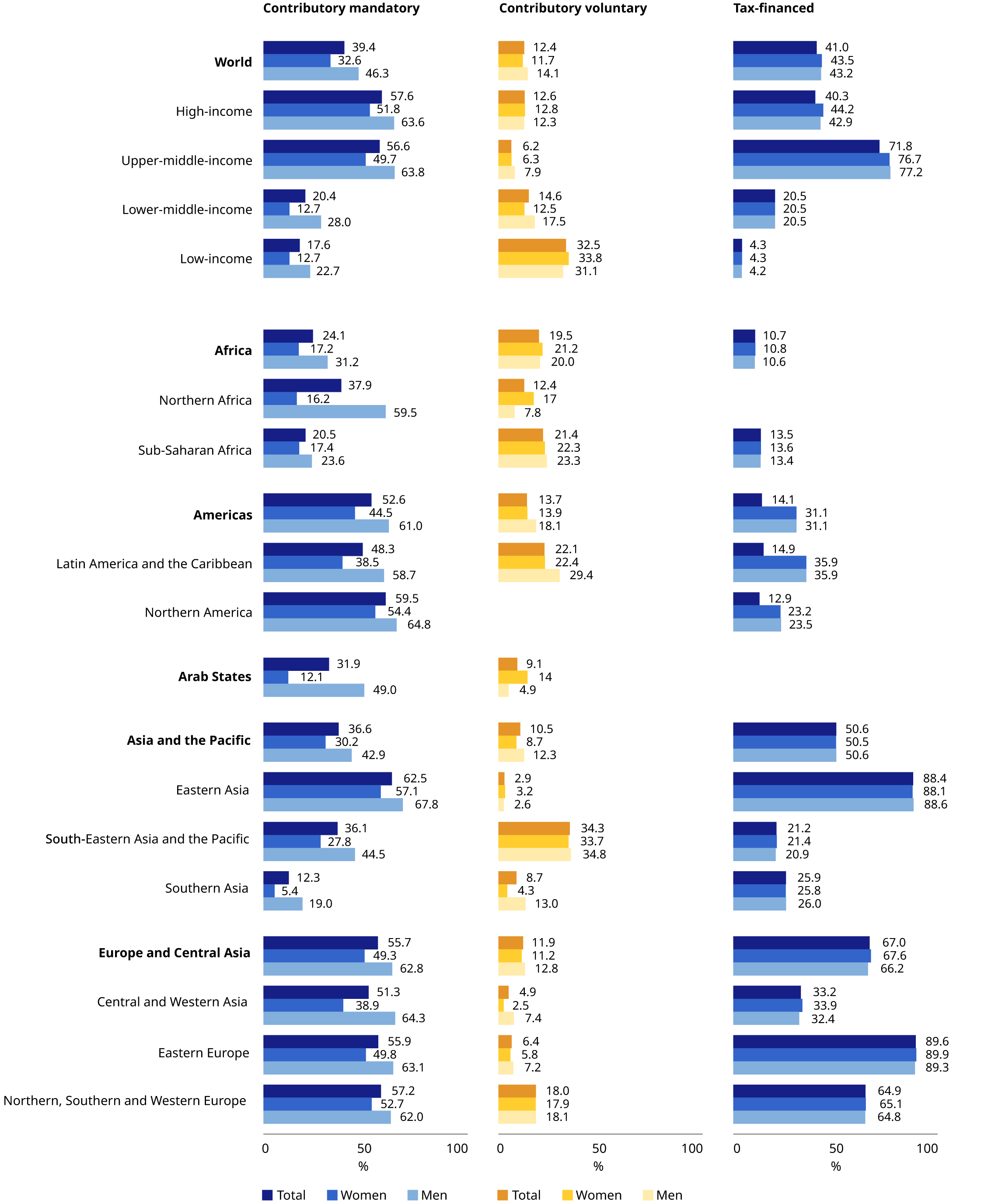

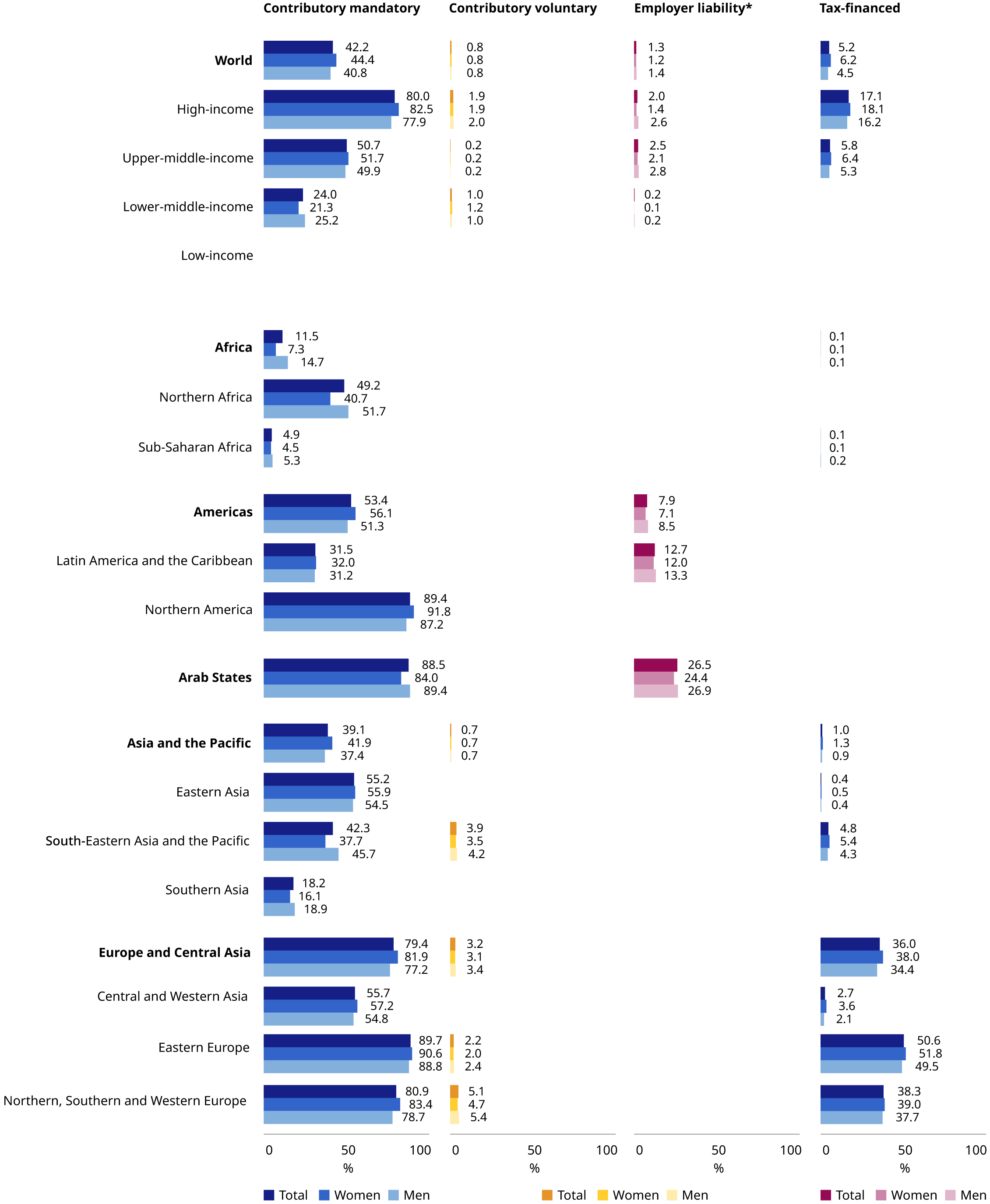

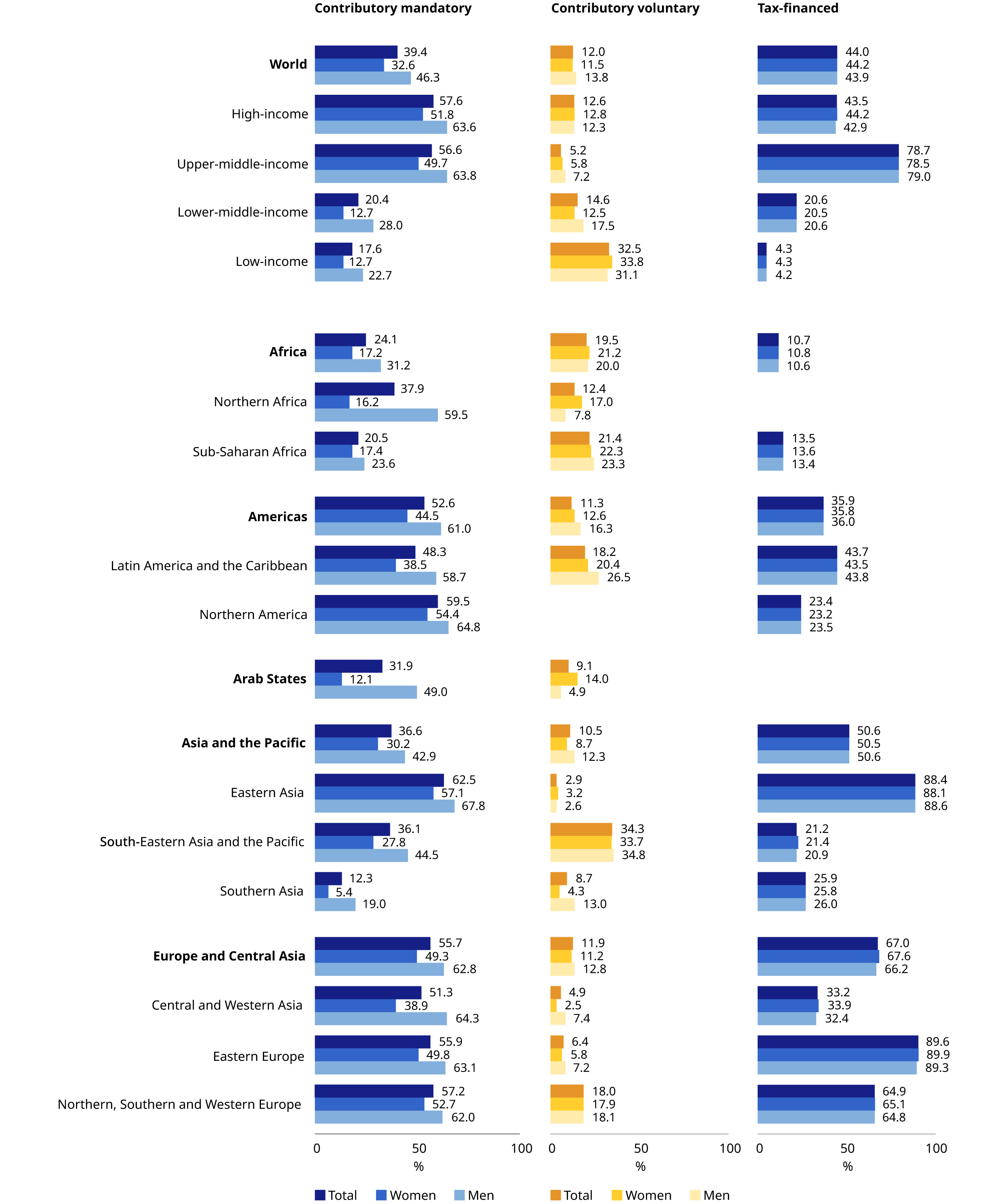

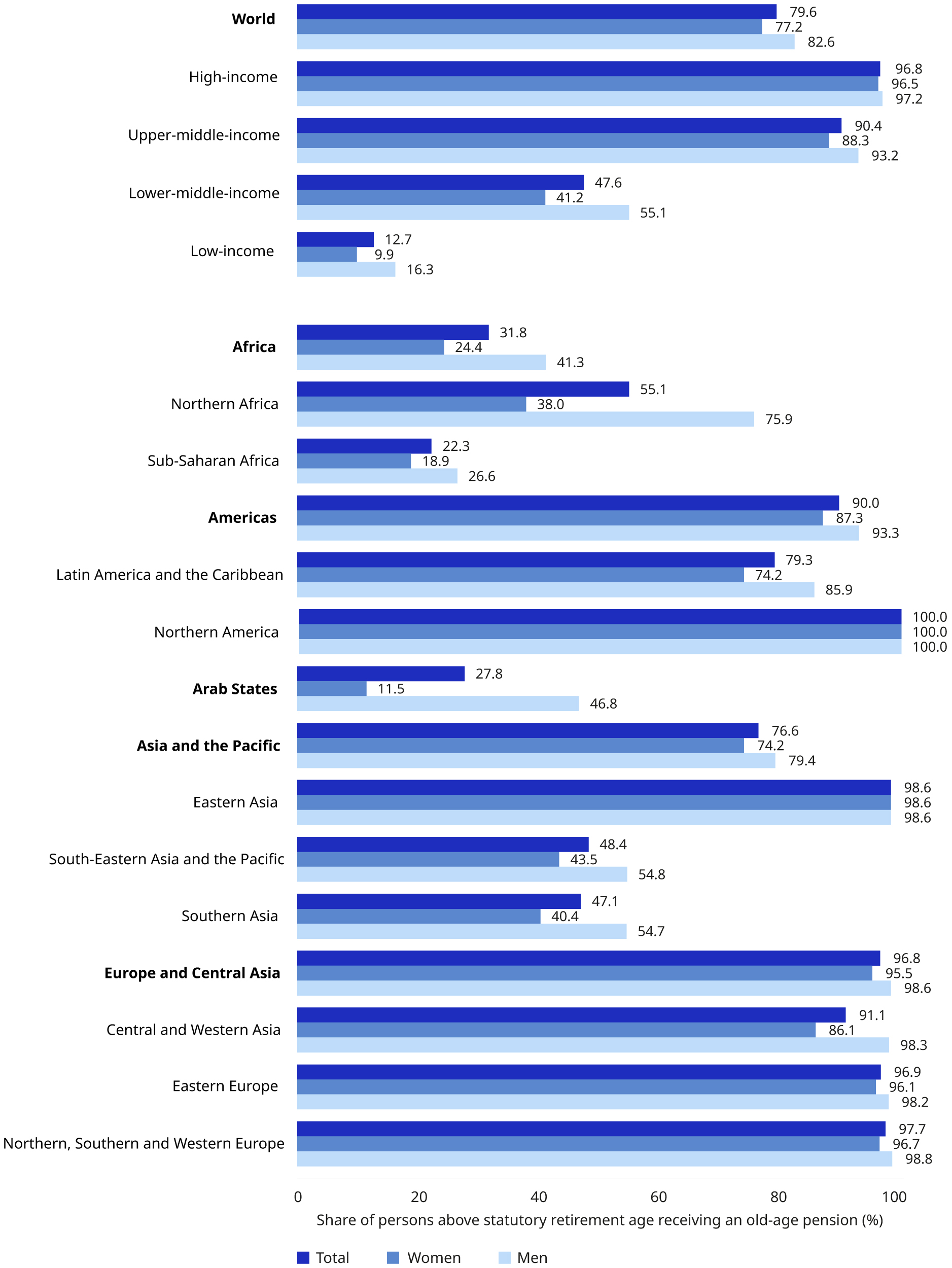

Worldwide, only just above one out of three pregnant women receives a cash benefit to compensate for reduced income generation capacities around the time of childbirth. The effective population coverage of maternity benefits has increased modestly between 2015 and 2023, from 29.6 to 36.4 per cent, with massive regional differences (figure 4.10). All regions experienced progress but increases were much more pronounced in Asia and the Pacific (an increase of more than 13 percentage points, from 25.8 to 38.4 per cent) and less in Africa (from 4.3 to 6.7 per cent) and Europe and Central Asia (from 77.4 to 79.4 per cent). Progress has also been much slower in low-income countries (from 1.5 to 2.6 per cent) and fastest in lower-middle-income countries (from 25.9 to 36 per cent). The low overall coverage and slow progress in low-income countries illustrate the extent to which they are left behind and uncoupled from global trends.

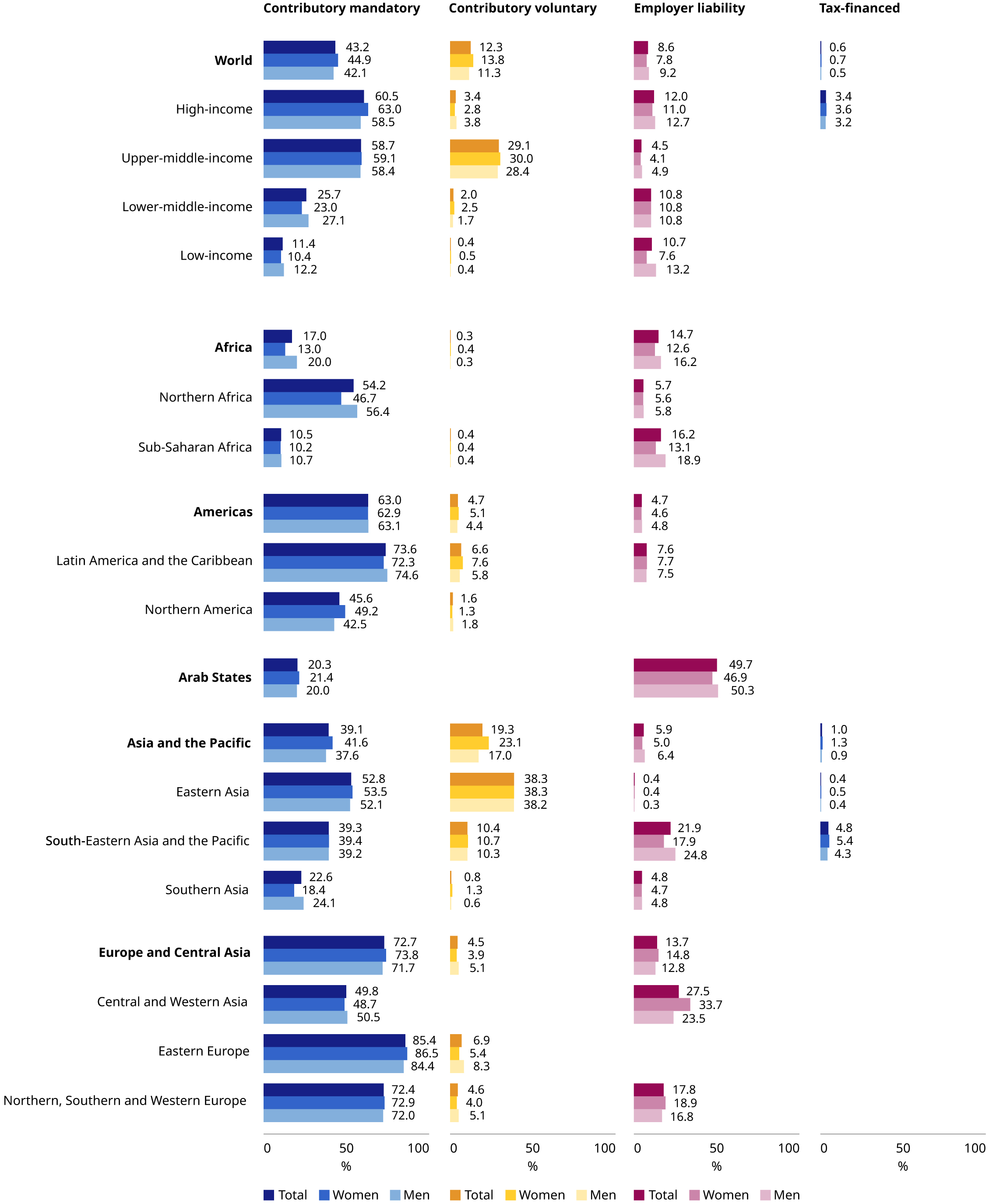

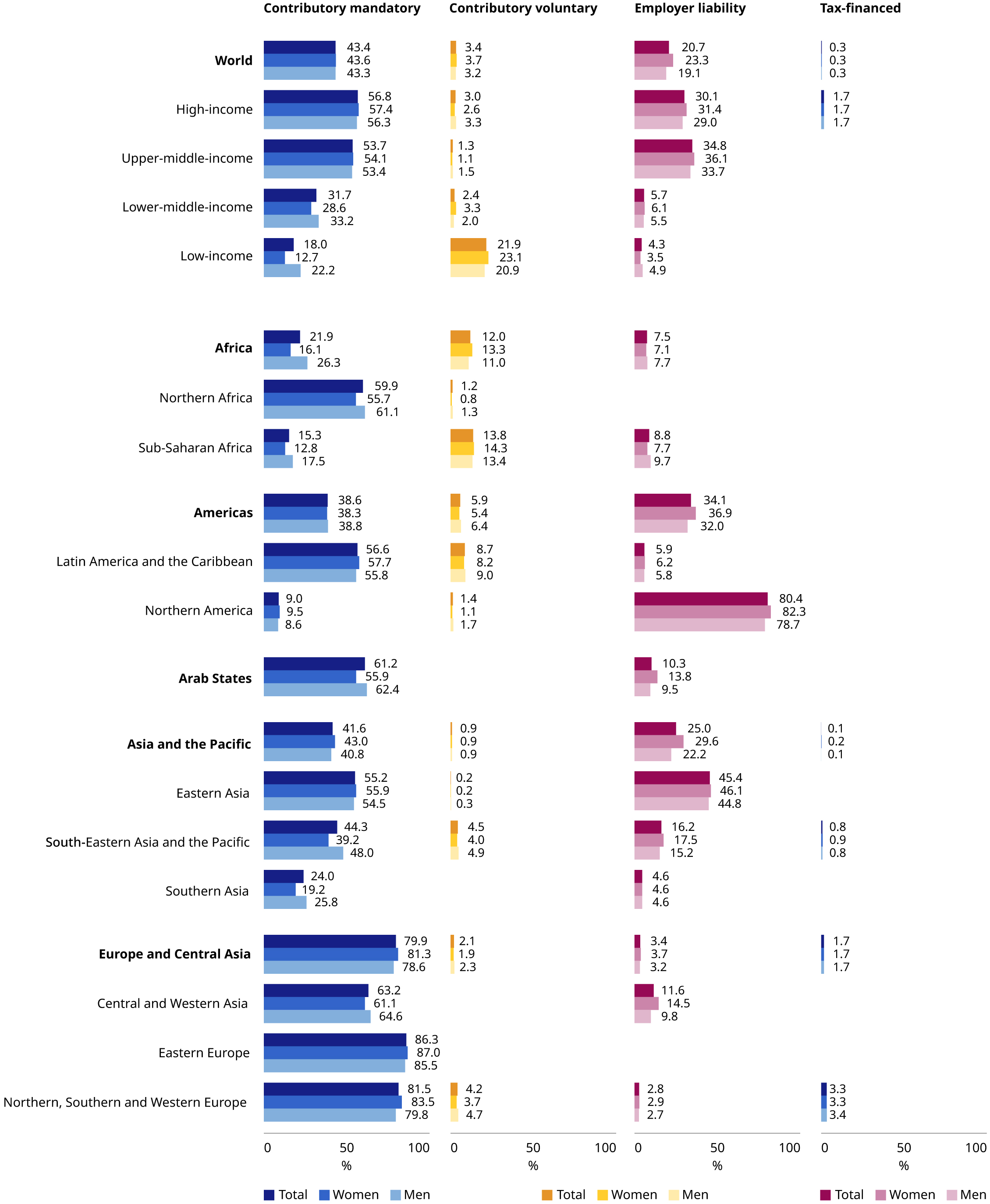

Figure 4.10 SDG indicator 1.3.1 on effective coverage for maternity protection: Share of women giving birth receiving maternity cash benefits, by region, subregion and income level, 2015 and 2023 (percentage)